The strange case of Johnston Atoll, where chemical weapons and atomic tests share the azure waters with birds, tropical fish and green sea turtles.

By Wilson da Silva

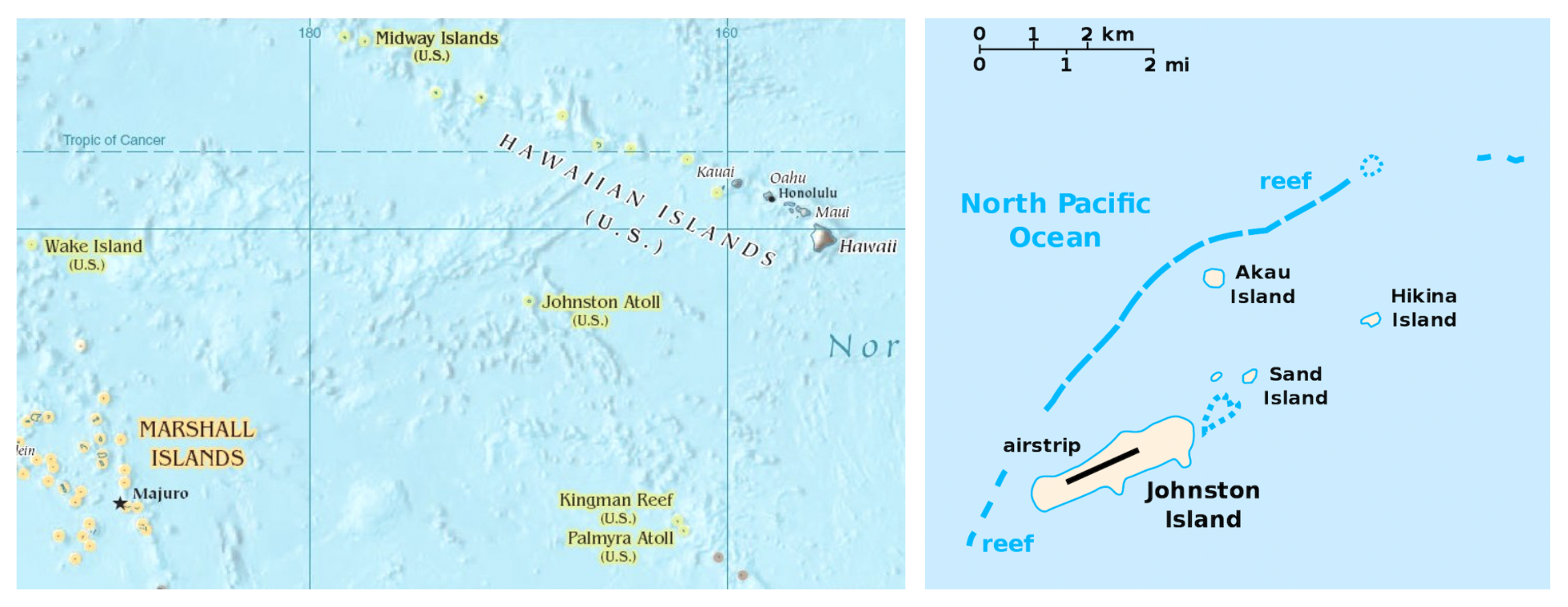

FROM THE AIR it is little more than a glorified aircraft carrier – an elongated islet of coral surrounded by a clear lagoon, small coral outcroppings and the dark asphalt of a runway cutting a swathe through the middle of the main island.

Yet, in what would otherwise be an idyllic setting, this remote corner of the Pacific is home to a nightmarish cocktail of death. It is Johnston Atoll, where 400,000 chemical weapons are stored, from where atomic tests were once conducted and where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service runs one of the most bizarre animal refuges in the world.

Located 1,200 km southwest of Hawaii, Johnston Atoll is a United States military facility. Working for the international newswire Reuters, I joined 70 other journalists on the first press tour of the atoll. Security is tight – nobody gets within 80 km of the atoll without the military knowing about it.

There are four small islands set within the coral lagoon, where 500,000 birds visit and 301 species of fish swim the shallow waters. Johnston Island is the largest, followed by Sand, Akau and Hikina islands. All add up to some 80 square kilometres of land.

The atoll is a limestone cap sitting atop the core of an ancient volcanic island which began sinking slowly 86 million years ago. The coral is thousands of metres thick, and although the shallow reefs are lush with varied life, the deep surrounding ocean is a biological desert. The westward flowing North Equatorial Current which girdles the atoll carries few nutrients near the surface, and the microscopic plant life on which most other sea creatures depend is scarce beyond the island chain.

But the current is diverted by the underwater mountain that makes up the atoll, and the turbulence throws up nutrients from the deeper waters nearer to the surface. Like a plough, the atoll cuts through the current and throws up a cloud of organic material behind it, creating a wake of rich marine life to the west of the island on which thousands of sea birds come to feed.

It is the only dry land and shallow water for millions of square kilometres of cold ocean, and many of the island’s 1,300 human residents – mostly American civilians contracted to the military and on short stays – like to tell you that it is one of the most isolated places in the world.

Two endangered species can be found on the atoll, the green sea turtle and the Hawaiian monk seal. The turtles spend their entire lives at sea except for brief visits ashore to deposit their eggs in sandy pits dug in shallow areas above the high tide mark. Adult turtles grow to weigh some 130 to 180 kilos, and can take 40 years to reach breeding maturity. Tagging by researchers suggests the turtles probably nest at the French Frigate Shoals, small rock outcroppings that are part of the Hawaiian chain and lie 850 km to the north.

The seals are mostly found in the northwest Hawaiian islands, although some often appear at Johnston Atoll. Nine seals were moved to the atoll lagoon in 1984, but none have taken up permanent residence.

By far the most visible animal life is the birds. Half a million use the atoll, many migratory and originating in North America and northern Asia. there are shearwaters and petrels, tropicbirds, frigatebirds and boobies, terns and noddies, shorebirds and waterfowl.

Some are large, like the black-footed albatross which has a wingspan of 2.25 metres, while others are as small as the Townsend’s shearwater, which has a wingspan of 32 centimetres. There are 13 breeds nesting on the atoll, 17 migratory breeds,14 that are uncommon or rarely seen, and eight that accidentally find their way there. Breeding is normally conducted between February and September.

Gas masks and rubber suits

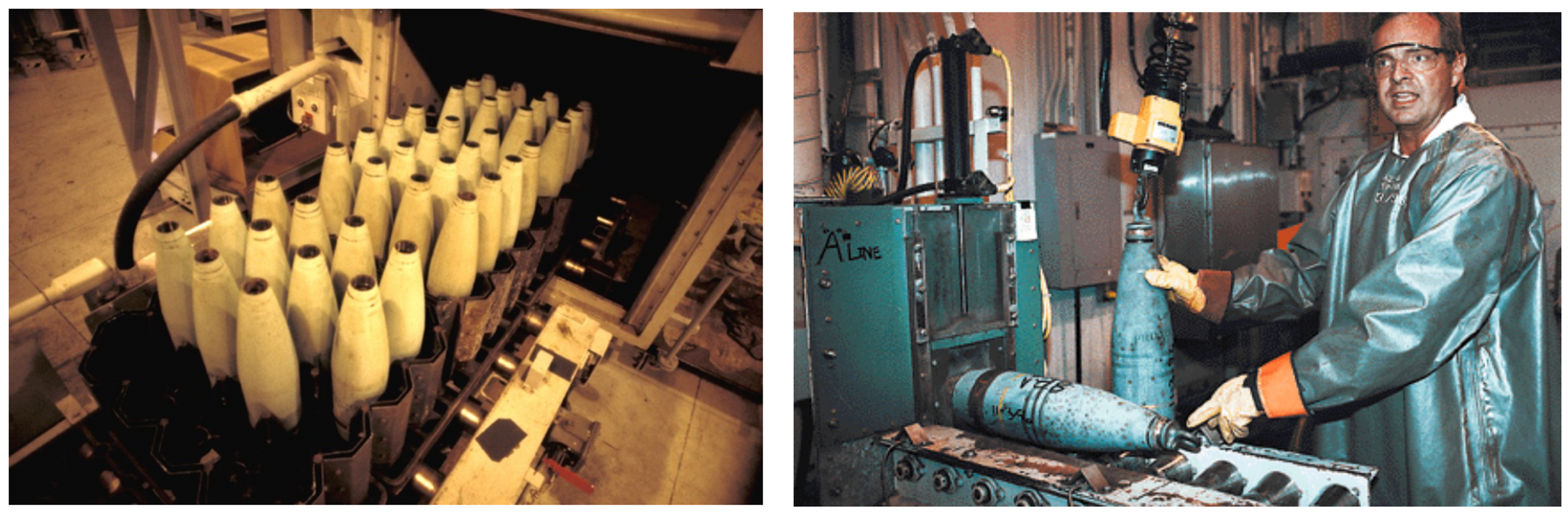

Although a biological oasis in an otherwise lifeless sea, Johnston Atoll is also the site for world’s largest chemical weapons destruction station. Here sit 54 storage bunkers, and buried in these metal and coral tombs are American missiles, mortars, bombs and land mines of chemical concoctions so feared they were never used in battle. So feared that in the 1970s the U.S. Congress outlawed their return to U.S. soil.

So here they stay, 6.6 percent of the United States’ chemical weapons stockpile, awaiting destruction mandated by a 1985 arms reduction treaty between the superpowers. Most of the 30,000 tonne American stockpile is to be obliterated by the end of the century under the treaty.

Hailed as a triumph in arms reduction, in reality many of the weapons on both sides are old and leaky, and had to be destroyed lest they contaminate military personnel. Another 104,000 chemical weapons from Germany were brought to the island last year, high-tech weapons that are the best in the U.S. inventory.

The incinerator facility dominates one section of Johnston Island, a towering lattice-work structure of metal pipes, girders and concrete sitting like a multi-storey petroleum refinery squeezed into a too-small piece of land.

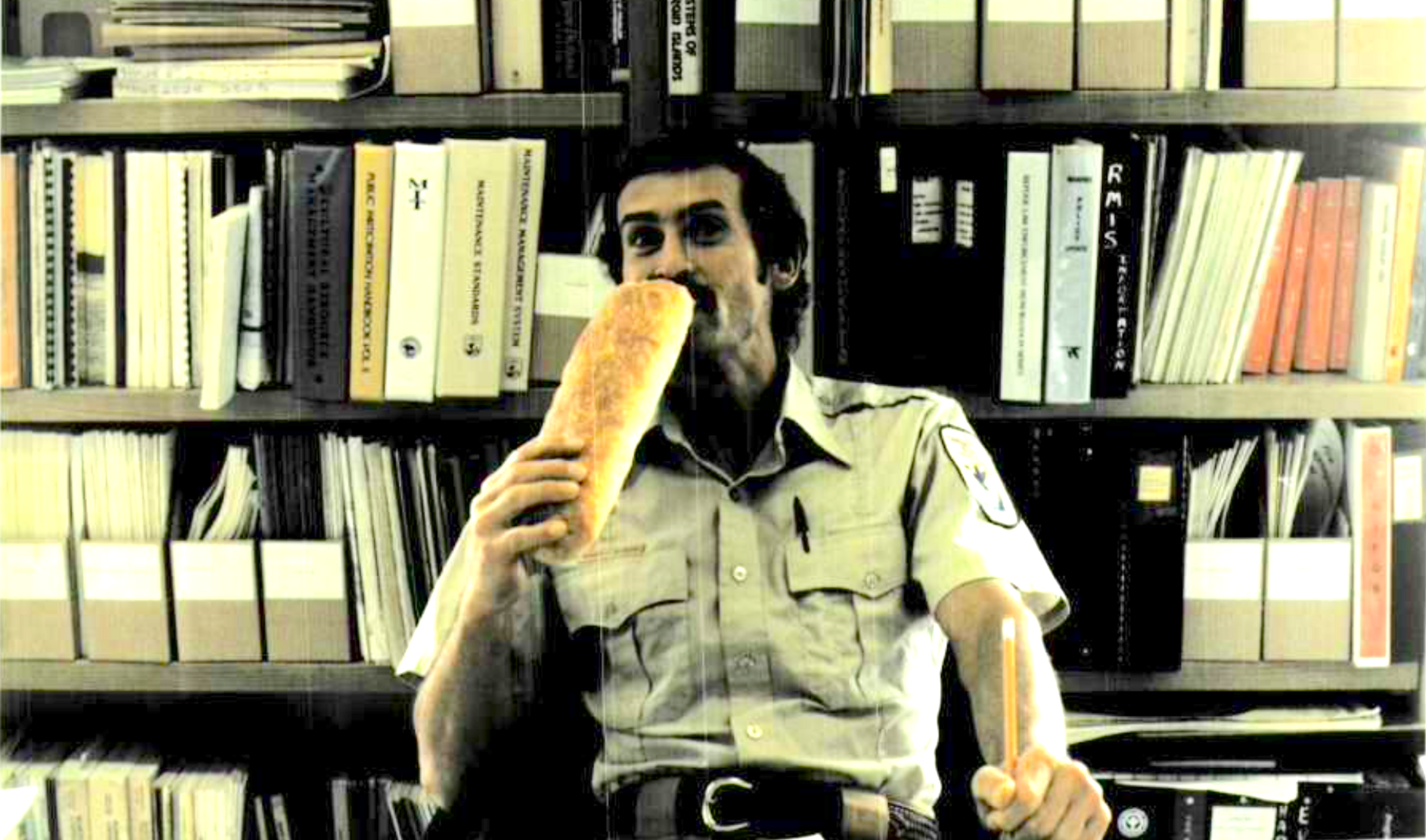

When visiting the low-lying atoll, you must prepare for chemical warfare. You are fitted with a gas mask, carry nerve gas antidotes in self-propelled syringes and must be ready to jab yourself within seconds of an exposure alarm sounding.

The locals like you to think they take safety seriously on Johnston. This tends to be a good idea – a nerve agent like sarin, odourlous and colourless, seeps through clothing and skin and soon restricts breathing, triggers involuntary urination and defecation, brings on convulsions and finally death. Mustard gas raises watery blisters hours after skin contact, and inflames the nose and throat.

Had a contamination alarm sounded, nine seconds was all we had to attach gas masks to our faces. If we felt symptoms of poisoning, we were to jab our legs with the syringes, and make our way to one of the safety buildings on the island.

They trained us for chemical warfare, but when we stepped off the military plane clutching our gas masks, I was struck by the beauty of the place. The sun sparkles on the seawater and the 28 species of coral give the atoll waters a cool, cerulean tone. Johnston Island is dominated by man-made activity, but the three other islets stretch into the distance in a semi-circle, and masses of birds can be seen on them.

Biologist Roger Di Rosa, atoll ranger for the United States Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), says that during the breeding season, the skies are blanketed with birds. Thirteen species nest on the island, and since dredging by the military expanded surface land in the 1960s, bird populations have increased.

“The greatest impact to the environment actually comes from the people who live here, and the infrastructure that’s needed to support them,” said Di Rosa. “That causes more a problem than the plant or the destruction of the weapons themselves. People are out on the lagoons and they’re boating or diving and they’re fishing, and that will cause an impact.”

Sewage is treated and then used as fertiliser on the human-inhabited areas of Johnston Island. Rubbish is burned or sent back for burial or recycling to the U.S. mainland, mostly California or Florida. Transport is largely via bicycle, and there are three for every resident on the island.

Cars are only used where necessary, and when worn-out, are burned to remove tyres and hosing, then buried in artificial reefs some way from the atoll. Di Rosa says this practice is safe and used elsewhere, only ferrous metals are sunk, and fish have started to aggregate around the artificial reef.

In every press handout, every briefing and every tour the military gave, environmental aspects were stressed. There are seven environmental professionals on the atoll, decisions are made in consultation with them and every effort is made to reduce the military’s impact on wildlife. They say Johnston Atoll complies with the strictest directives the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has set, and the atoll is a cleaner and more environmentally safe place than big U.S. cities like Los Angeles.

Why is the military so eager to be seen as “green”? The Johnston Atoll incinerator is a prototype, and another eight are to be built across the United States, adjacent to bunkers holding the remaining American chemical weapons. With local opposition rising, the military is keen to get Johnston Atoll right – to show how safe and environmentally friendly it can be to burn chemical weapons, even in your own backyard.

One U.S. Air Force officer asked me during lunch, why is the media so intent on painting Johnston Atoll as a chemical weapons dump with a deadly, nightmare incinerator? I suggested that even if the Johnston Atoll operation is squeaky clean, Americans had so often trashed the Pacific that, if one time out of 10 they get things right, everyone will suspect a rat and dig like hell to find it.

The USFWS owns the atoll, but the military operates it and helps to fund wildlife operations. Another biologist operates on the island, and the military have hired bird and fish experts from California and Massachussetts to study atoll life.

Di Rosa and the military make strange bedfellows. On an island from which nuclear atmospheric tests were launched until 1962, where Vietnam era Agent Orange has spilled into the sea and where the U.S. keeps 6.6 percent of its chemical weapons stockpile, he manages a wildlife refuge that was mandated into existence before scientists had even split the atom.

During the tour, a highly-ranked island resident told me: “You know, we’re not popular in Hawaii”. The newspapers in Honolulu made this plain, often quoting environmental activists who say an accident on the island would send a cloud of deadly nerve gas floating over the Pacific. The prevailing wind is from the south, and the Hawaiian islands lie to the north-east.

There are 15 independent nations in the Pacific, and none are pleased about what is being done on the atoll. They worry about emissions from smokestacks, that a plane crash on the incinerator or the bunkers could throw up a cloud of chemical gas over them, or that the atoll could become the world’s chemical weapons dumping ground, a global 'backyard burner' for hazardous wastes.

The military and USFWS admit a catastrophic plane crash could release chemical weapons into the air, but they prefer to quote the environmental impact statement completed before the construction of the incinerators. It says such a chance is “less than one in a million”.

A collision into the incinerator would only release the small amount of gas kept inside the facility at any one time. The bunkers are the reinforced type used to house explosives, and a direct hit would at worst release the contents of only a few bunkers. Under this scenario, few of the weapons would likely be breached, the military says. The explosives inside rockets and mortars have been removed, and only the chemical warheads are stored here.

Either way, the effect on the environment of such a catastrophe would depend on wind activity and direction – still air could allow gases to hang near the atoll and percolate into the local life. In the worst-case event, with all chemical weapons released under the worst possible conditions, a “death plume” would likely reach 23 km around the island, but could extend 100 to 120 km. Beyond this, the gases would fall below lethal concentrations.

Hawaii is 1,200 km northeast, and the Marshall Islands some 2,350 km southwest – outside of range. But one University of Hawaii scientist says under certain conditions, the plume may reach Hawaii, and environmentalists worry what contamination of the area’s fish would do to the food chain. And how do you prevent contaminated fish from ending up on the tables of nearby islanders?

It is the sort of thing that worries Pacific nations. Although a meeting of the South Pacific Forum in July 1990 agreed that chemical weapons should be destroyed, they urged the U.S. to dismantle the incinerator once stockpiles already on the island are eliminated.

Days before our tour, U.S. President George Bush flew to Hawaii and met 11 of the area’s leaders and representatives in what was dubbed a 'Pacific Summit'. With plenty of flags, military bands and red carpet, Bush met them for two hours and later said his country “had no plans” to use the atoll to burn other chemical weapons or later use it to burn hazardous waste.

For many after the meeting, including some of the Pacific leaders, the question remained – what do you do with a US$420 million high-tech incinerator, once the weapons are incinerated in 1994? With civilian opposition to the planned incinerators growing in the U.S. mailand, speculation is rising that the U.S. Congress may buckle under pressure and take the easier political option of banishing all chemical weapons to Johnston Atoll.

Sometimes more Club Med than Pine Gap

Despite a feeling that the possibility of death is only a malfunction away, life can be pleasant on the atoll. It often appears a mixture of demilitarized zone and holiday resort – wire fences and palm trees, decontamination rooms and softball teams, armed military police and a nine-hole golf course.

“We’ve got a six-lane bowling alley, movies every night and softball is really popular,” Curtis Rodgers, a civilian technician, told me. “A lot of people fish out there. Scuba diving is excellent, and you can sail and waterski.”

I later lunched at Johnston’s Tiki Lounge, the atoll’s watering hole and the only pub in 1.3 million square kilometres of featureless ocean. From near the water’s edge on Johnston’s north side, I saw a windsurfer bearing into the breeze far away. Careful inspection revealed the windsurfer wore a familiar green pouch which I could only assume held, like mine, a gas mask and two syringes.

Life can sometimes seem more like Club Med than Pine Gap. Atoll residents have overnight golf tournaments, volleyball clinics, an Olympic-sized swimming pool, basketball games and a daily newsletter called The Breeze. A store sells souvenir t-shirts and caps, one amusing one proclaiming “Hard Rock Café, Johnston Atoll”.

Residents get 13 channels of cable television via satellite, watch first-release movies every night at an open-air cinema, and have dances every two weeks. At such events, the atoll’s 300 women are often beset by scores of eager men.

“It’s really a small town,” said Jake Sitters, a civilian clerk who has been on the island for 28 years. “Just about everybody knows everyone else, and everybody knows what everybody’s doing and who they’re doing it with.

“Sometimes not all the women turn up to the dances, so you just sit around with a bunch of guys around a table, drinking and talking stories and here’s all this good music going to waste.”

Women were at first not allowed on the atoll, ostensibly because it held stocks of Agent Orange, a Vietnam War era defoliant linked with birth defects. When stocks were destroyed in 1977, women began to arrive, and Sitters says the social tinderbox some had predicted did not eventuate. “At first we thought we were really going to have trouble, you know, the men all vying to be the rooster. But it didn’t happen. We’ve had only two or three instances where guys have fought over a gal.”

Sitters, a 61-year-old Texan, is owner of the island’s only dog, Patches. Black with small white blotches and of indeterminate breed, he brought her to the atoll when she was six weeks old and it has lived with him ever since.

Twenty years ago, he befriended a Hawaiian monk seal he found lying on the beach. After a few careful approaches, they soon became friends and spent seven months playing by the water or on the ramp of the island’s boat house.

“We had a tremendous time," he recalled. "I’d lay down on the concrete ramp and she’d come up, put her flippers over me she’d nibble on my ears. If I saw her head out on the water I’d just clap my hands and boy, she’d come right in to me. One time she followed me all the way to the barracks looking for me, scared the hell out of the guys.”

WhenSitters returned from an overseas vacation, the seal was gone. “For the most part, life here is – I hate to say idyllic, but that’s what it has been for me. There’s just an endless amount of things to do, and anybody who complains there’s nothing to do on Johnston Island, it’s their own fault they’re bored,” Sitters said.

It may seem idyllic, but it is not a resort. A failed nuclear missile launch nearly 30 years ago has left one section of the atoll contaminated by 230 grams of plutonium, and a large spill of the Agent Orange in 1971 left one corner of Johnston sealed off. The military, keen to display its environmental credentials ever since the chemical weapons incinerator was installed, began a thorough clean-up of both contaminated zones in July.

They told the travelling press that their US$420 million high-tech incinerator was safe. So safe that 79 rockets, carrying warheads filled with a lethal nerve agent, were burnt while reporters were led through the destruction station.

At one stage, a temperature fluctuation in one furnace chamber forced the plant to shut down for 44 minutes. It was one of the nagging glitches which have kept the facility, the first of its kind in the world, operating for only 24 percent of the time expected. Six times since trial incinerations first began in June 1990, contamination alarms have sounded throughout the facility, only later to prove false. Conveyor belts that carry non-lethal munitions parts have repeatedly broken down.

“When the plant operates, it operates very well,” technical director Charles Baronian told reporters. “Because the problems are mechanical, I would primarily characterise it as a design flaw, but not a basic flaw.” He stressed to uneasy journalists that the breakdowns do not endanger the safety or integrity of the facility, and shutdowns only occur because site managers take no chances, even in non-critical breakdowns.

Throughout the island, 106 automated monitoring stations take 29,000 readings daily. They scan the air in workplaces and around the island, sounding alarms when they detect minute quantities of nerve agent or blister gas.

Colonel George McVeigh Jnr is the kind of ramrod-straight U.S. Air Force officer you would expect to be in command of the island. At the end of our press tour, when the sun began to set, we heard a bugle outside playing the Star-Spangled Banner as the U.S. flag was taken down. McVeigh stopped an answer to a journalist’s question mid-sentence, and stood at attention until the bugle stopped.

The civilian contractor operating the island is Raytheon, the U.S. company which built the Patriot missile interceptor that became a darling of television news footage during the Gulf War. Some 758,000 litres of fresh water are extracted from the sea every day, and the facility costs US$18 million a year to operate.

From bird sanctuary to atomic tests

Johnston atoll was discovered in 1796 by Captain Joseph Pierpont, an American commanding the brig Sally. There were no people on the atoll, and there is no record of Polynesians ever having reached the islands. It was named in 1807 by an eager young British lieutenant in honour of his captain, Charles J. Johnston, after the crew of the HMS Cornwallis briefly sighted the atoll while headed elsewhere.

The first serious study of the island’s ecology was in 1923, and the results led the United States to declare it a bird sanctuary. Eleven years later it was handed to the U.S. Navy, but the wildlife refuge provisions remained.

The Japanese briefly shelled the atoll on their way home after the bombing of Hawaii’s Pearl Harbour in 1941. Airlifts were conducted from the atoll during the Korean War in the early 1950s, and in 1958 it became a nuclear test site: three atmospheric and one underground atomic test was conducted at Johnston Atoll.

In the 1970s, ageing chemical weapons from Okinawa in Japan were transfered to Johnston, later joined by Agent Orange stocks which were eventually destroyed in 1977. Last year, 104,000 state-of-the-art chemical munitions from U.S. bases in Germany were shipped in, and a forgotten chemical dump on the Solomon Islands was dug up and brought to the atoll.

Although the schedule sees the incinerator, known as JACADS (Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System), operating until 1994, the recurring delays mean that it will now probably operate for a few years more. Once complete, the military says JACADS will be dismantled.

Or maybe it will be mothballed, just as the atoll’s capability to conduct atmospheric atomic tests has been maintained despite the superpowers signing the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1962.