By Wilson da Silva

WE’VE ALL HEARD it for decades now. The oft repeated mantra from East Asian leaders that the region cannot afford Western luxuries like an open democratic process, human and political rights and a misplaced concern from the environment.

After all, they have nations to build. Economic development is the first priority. And look at the result: hasn’t East Asia become the economic miracle of the late 20th century: the so called Tiger Economies?

During the 1980s and early 1990s, the spectacular economic rise of East Asia had indeed left economists in the industrialised world wondering. Political theorists were also intrigued: those on the right of the political spectrum suggested that East Asia’s propensity for authoritarian rule coupled with a pro-enterprise culture was the key. Those on the left argued that it was government intervention: strategically targeted subsidies and tax breaks for value-added manufacturing like automobiles and aerospace, or government coordination of industry aimed at capturing a slice of emerging industries like computer hardware and electronics.

Even the World Bank, an ivory tower of neo-classical economics and arch-defender of free trade and a hands-off approach to business, has only recently admitted that government intervention has helped “marginally” in the creation of the Asian economic miracle.

But in the past few years, a different theory has emerged among economists: that there is nothing unusual in the rise of the Tiger Economies. That the spectacular growth rates they have experienced in the last 17 years is due to the simple fact that they had a small base to start with. Put simply, they have grown because they were so under-developed to begin with.

And – and here’s the clincher – East Asia entered its growth phase in the early 1980s, just as the rich economies of the world were experiencing the most sustained economic expansion in modern history.

In effect, the theory goes, they were just riding on the coattails of a boom in the industrialised world. East Asia was developed enough to move into more value-added manufacture. Airports, shipping, roads and telecommunications were adequate if somewhat under-developed, while labour costs were low, natural resources plentiful, and governments very pro-enterprise.

But as we now know, the growth cycle in the industrialised world was funded by massive debt. While Reagan’s deep cuts to U.S. taxes triggered a consumer and corporate spending frenzy that lasted throughout the 1980s, it created a trillion-dollar budget deficit, turning the world’s richest country into the largest debtor. In Japan, the euphoria triggered inflated property prices and wild stockmarket speculation. In Australia, loose loans and shonky corporate deals dominated the economic landscape.

When it all came crashing down following stockmarket crash of 1987, the industrialised world developed a deep aversion to debt. Recession ensued in the advanced economies, during which companies began the most sustained cost-cutting and reduction of the workforce seen in modern times. Again, East Asia prospered: cost-cutting meant that much of the manufacturing that took place in the heartland of the developed world chased the cheap labour of the developing world. East Asia benefited more than any other region.

Over the past year, we have seen the expansion of East Asian economies slow: instead of growth rates of 10 per cent and above, economists have been forecasting rates of 8 or even 7 per cent. This is expected, argued those economists who believe that it had all been due to standard growth theory anyway: East Asia’s economies were now maturing. Granted that by Western standards, the region’s growth rates are still high: most of the developed world is struggling to reach economic growth of even 3 per cent, and the United States is considered to be in the midst of a major boom at nearly 5 per cent growth.

But as East Asian economies slowed, and the money markets realised that the halcyon days of double-digit growth had passed, attention turned to the economic fundamentals. Particularly debt. And suddenly, East Asia didn’t look so rosy. It became obvious that part of East Asia’s growth was being funded by debt. Massive debt, the kind that is hard to sustain unless you have equally dramatic growth rates.

Take Thailand: debts of US$355.6 billion, or nearly double the gross domestic product of the whole country. Or Malaysia: debts of US$165.9 billion, or 1.7 times the amount generated by the whole economy in a year. But for the fact these countries were in East Asia, the world would have called in the receivers long ago.

In the end, it was the currency markets that said enough was enough. Every day, more than US$1,000 billion slush through the world’s foreign exchange markets, dealers reacting to the smallest change in a country’s domestic interest rates, foreign debt or other economic fundamentals. They are extraordinarily powerful, but largely uncoordinated in their approach; they act in self-interest, and not even the central banks of the industrialised world can hold them back if they decide to dump a currency.

At some point, some of them decided to do just that to Thailand’s baht. The dream run was over, and they pulled the ripcord on the currency. Soon, others followed suit, triggering waves of selling that saw the currencies of East Asia’s most indebted countries – Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia – plummet by more than a third in a matter of weeks.

The rest is history. Thailand, a country whose growth rates left industrialised world looking lame, had to beg those same countries for US$17.2 billion to avoid a collapse. Malaysia has shelved multi-billion-dollar projects and cut government spending. Indonesia has called in the International Monetary Fund to help it get the economic house in order.

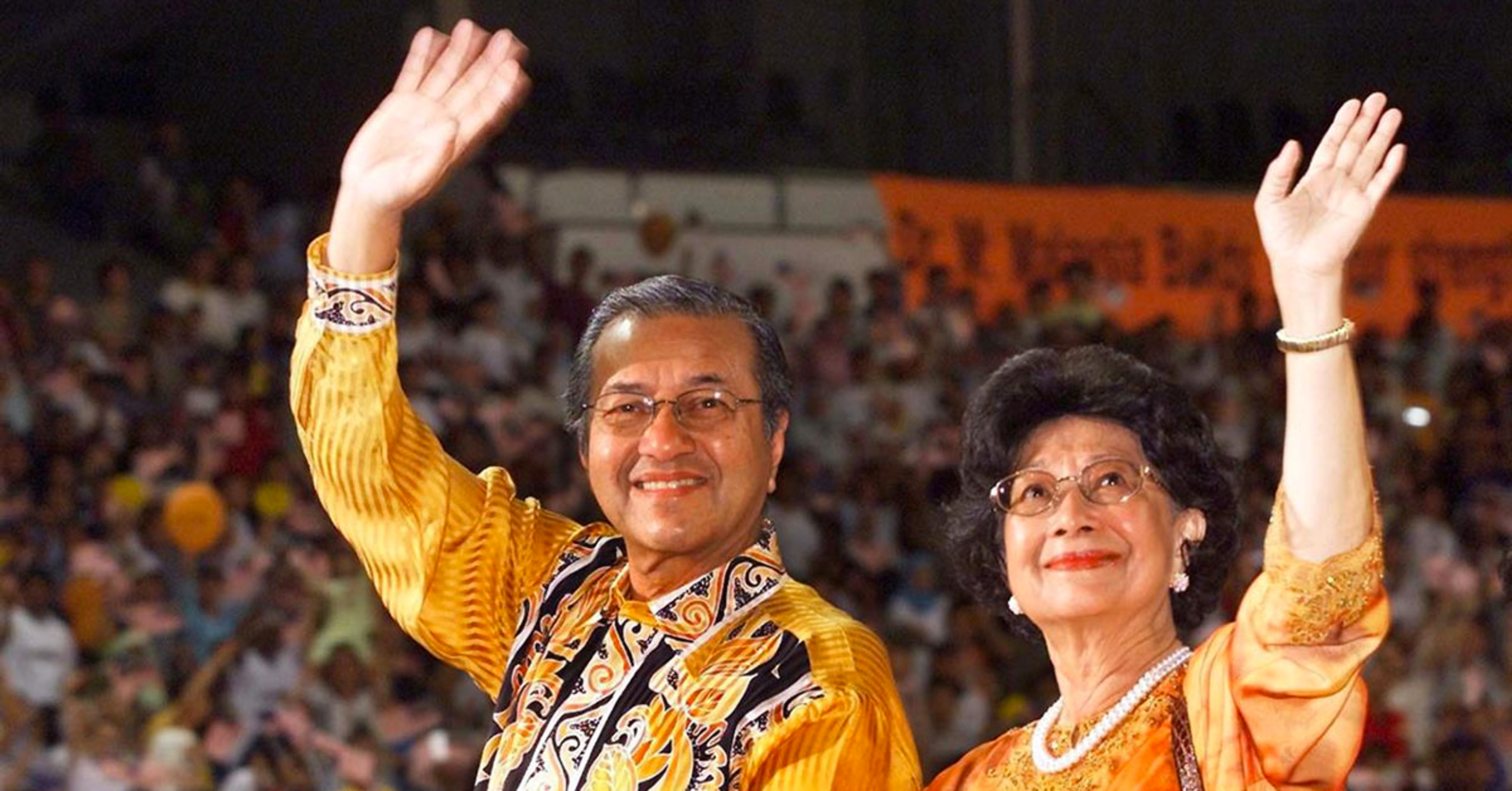

The ramifications may be a lot more severe that most people think. Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad has blamed the fall in the Malaysian ringgit on American-Hungarian currency speculator George Souros, and even a hinted at a conspiracy of Jewish financiers. And yet, it is his leadership that has been damaged by the affair.

The most interesting repercussions are likely to be in Indonesia. The New Order regime of President Suharto, in power for 31 years, has long prided itself on its economic credentials. These have been impressive enough for Australia’s Deputy Prime Minister Tim Fischer to call Suharto one of the greatest figures of the second half of the 20th century.

Again and again, the Indonesian government has justified the repression of dissent, quelling of labour movements and dismissal of human rights on the grounds that economic growth and development requires stability. All other considerations – civil rights, the environment, democracy – have had to take a back seat.

But with the collapse of Indonesia’s rupiah and the flight of capital from the country, Suharto’s economic credentials are looking very tattered. And the self-proclaimed legitimacy of his regime looks a little empty. Even tawdry: you would have to be blind not to notice that Pak Harto’s family and friends, his military brethren and aides, have been the biggest beneficiaries of economic development thanks to cosy deals and kickbacks when the money was flush.

Now that the party is over, the bills are coming due. Sadly, it will be “the little people” who will pay most: prices for basic foodstuffs will rise, government health programmes will be cut, public projects cancelled, and jobs will disappear.

The rationale for the repression of dissent and the denial of rights in Indonesia, and possibly elsewhere in the region, may well be seen for what many think it really is: a convenient excuse to concentrate power and wealth to a select few.

The next few years will tell. But indications are that the Asian economic miracle was really a mirage. If it was ever a reality, it has been squandered by the greed of those at the top of the food chain, who replaced colonial masters with an indigenous but just as privileged elite.

If the Asian economic miracle ever existed, it is quickly going up in smoke, like the countless square kilometres of Indonesian rainforest now burning uncontrollably in the name of profit.

Wilson da Silva is a Sydney journalist and former foreign correspondent for Reuters