Where to begin in this huge, saturated, sprawling survey exhibition of British women, political, feminist art featuring over 100 artists, spanning 20 years, from 1970 – 1990? The Tate curator of British Contemporary Linsey Young thoroughly researched her material and artist, and should be commended for putting an such an exhibition together. She claims feminist protest and activism as art, as well as featuring many over-looked artists and artists that have now become household names; Sonia Boyce, Chila Kumari Burman and Lubaina Himid, for example, artists who all came from humble working class beginnings, when art schools were truly independent, fiscally free; we received grants, before the Blairite rise of the super universities that subsequently swallowed up every art school in the country.

To avoid exhaustion, I suggest two visits, or why not disrupt the flow or order of the displays, start from Room 6 and make your way to Room 1 instead? There are six exhibition rooms, starting with women artists from the early 1970s. By the time you get to room 5 and 6 your mind may draw a blank. I’m not a scholar, nor an academic but I am a late boomer, family of working-class Mauritian immigrant parents who both worked for nationalised service industries. I was seduced by the art scene from the early 1980s. I remember the situationist style public interventions, the subverting of sexist advertising billboards, the most iconic being the car ad “If it were a lady, it would get it’s bottom pinched”, to which an anonymous responder graffitied “if this lady was a car she’d run you down”. I remember Greenham Common, I also remember the friendly fire between radical feminists, socialist feminists, anarchist feminists, black women artists, conceptual artists, performance artists, white feminists, black feminists, black LGBT, white LGBT, the working class, the middle class, the anarchists, Asians aren’t black, black is a political colour etc, etc, etc…sometimes it was furious. Social media didn’t exist, intersectional feminism was still in-utero until 1989 and has now morphd into an ideology that now hates most white feminism, and gleefully cancels anyone who isn’t part of the ever-expanding “be nice” spectrum of oppression. While the alliances and divisions of the 1970s/80s could be charged, it didn’t appear hateful….unless you were Margaret Thatcher – the godmother of neo-con/liberal/libertarian/reactionary feminism – did Thatcher's artistic equivalent exist in the arts/activist world in those golden years? Or were they ignored and forgotten?

Oh, those halcyon days of radical politics and art, before the contemporary narcissism of identity politics. If there is to be a Women in Revolt! Mark II from 1990 – 2025, I think I can make some speculation on what that may look like – expect lots of preferred pronouns and men pronouncing their woman-hood.

Attending the preview/private view in early November felt like a reunion party, a joyful celebration. I met many old faces from the Black Arts Movement and works that I fondly remember from the mid-80s onwards, room 5 is where it’s at, it’s where my cultural tribe hang. There are too many to mention, but here are three artists I would recommend you make a beeline for.

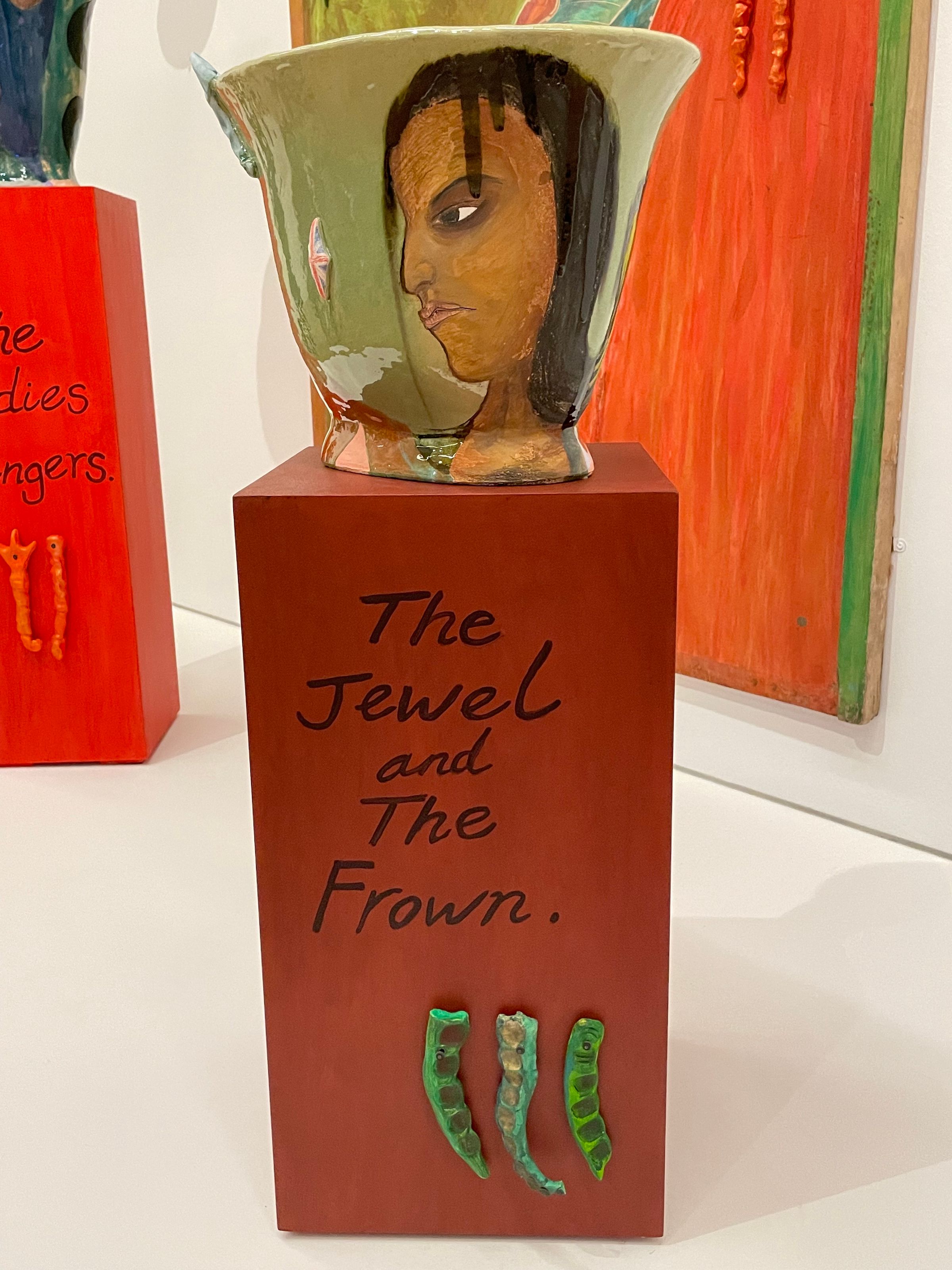

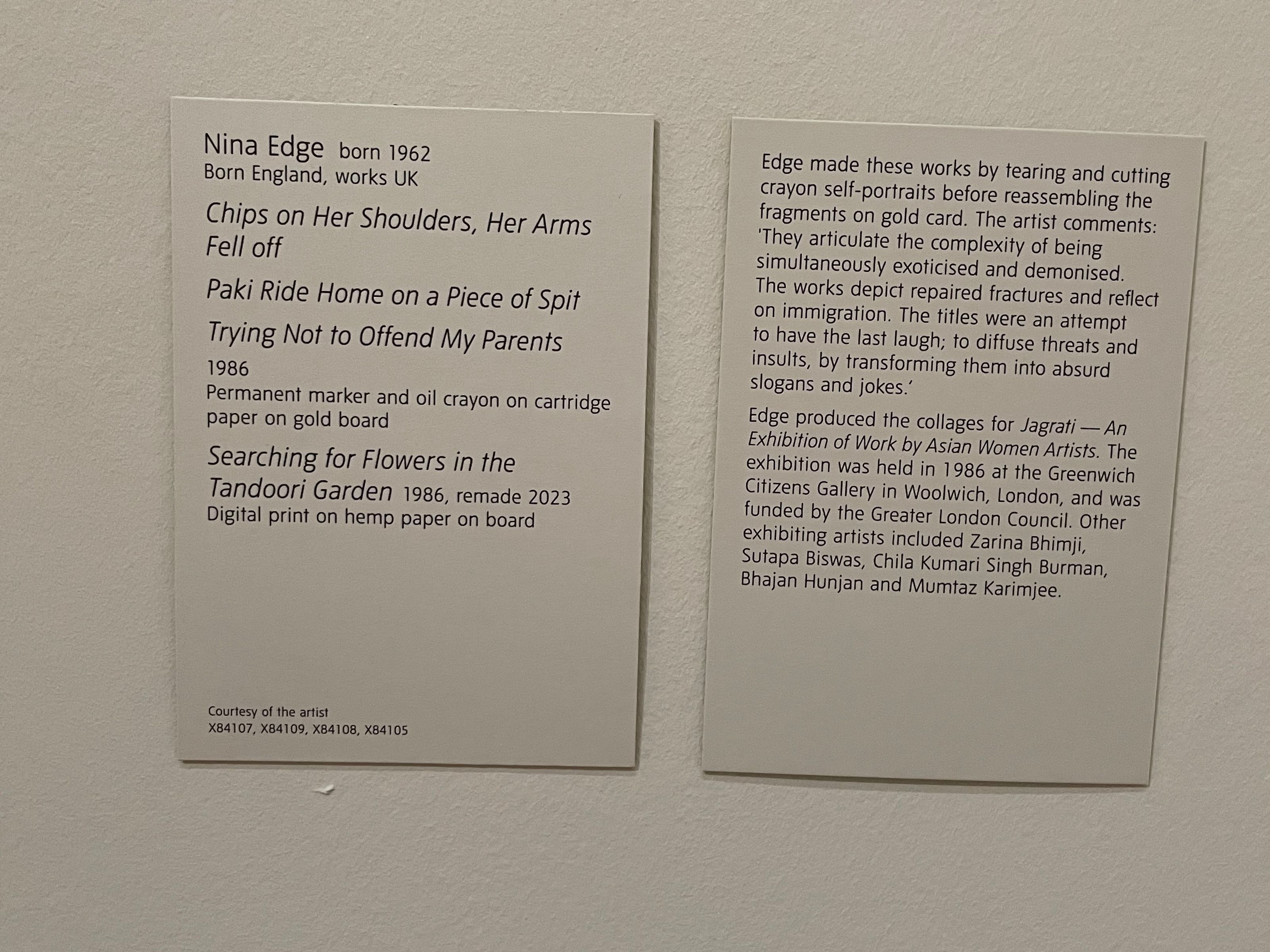

Nina Edge is bi-racial, of Ugandan Indian and English parentage, who lived in rural England before moving to more urban environments. It’s a joy to see Snakes and Ladders, a mixed-media work harking back from 1985, and remade especially for this exhibition in 2023 as most of the original features of the work were either lost or given away. This is work that hasn’t been exhibited for over three decades. It was originally created at a time when India-mania reigned on British TV and in the cinema; The Jewel in the Crown (1984), The Far Pavilions (1984), A Passage to India (1984) as well as Gandhi (1982). All were huge commercial successes, it seemed the west was still nostalgic and fascinated for the loss of India, the Jewel in Britain’s great empire. Edge plays with this orientalist love of India with humour, puns and wit. A fave vegetable in Asian and African cuisine, okra AKA Lady’s Fingers creep about in the installation like phallic alien creatures, an Indian woman unleashes a snake from a pot, phrases can be seen, Living in Britain and The Indian Rope Trick.

Interestingly, I was listening to a podcast conversation during lockdown between another bi-racial artist, the Indian-Jewish Anish Kapoor and Greek economist/politician Yanis Varoufakis. Kapoor talked about the racism he also experienced as an emerging artist getting noticed, a critic referred to his work as using the “Indian rope trick”, labelling him as an “Indian Artist”. The art world couldn’t see him as simply an artist, who went to an English art school. Nina Edge probably was also labelled as an Indian artist, but she was born in England and went to study Ceramics at Cardiff School of Art. Her other series of paper-based works featured in the exhibition playfully attacks British racism, disarming the insults and stereotypes.

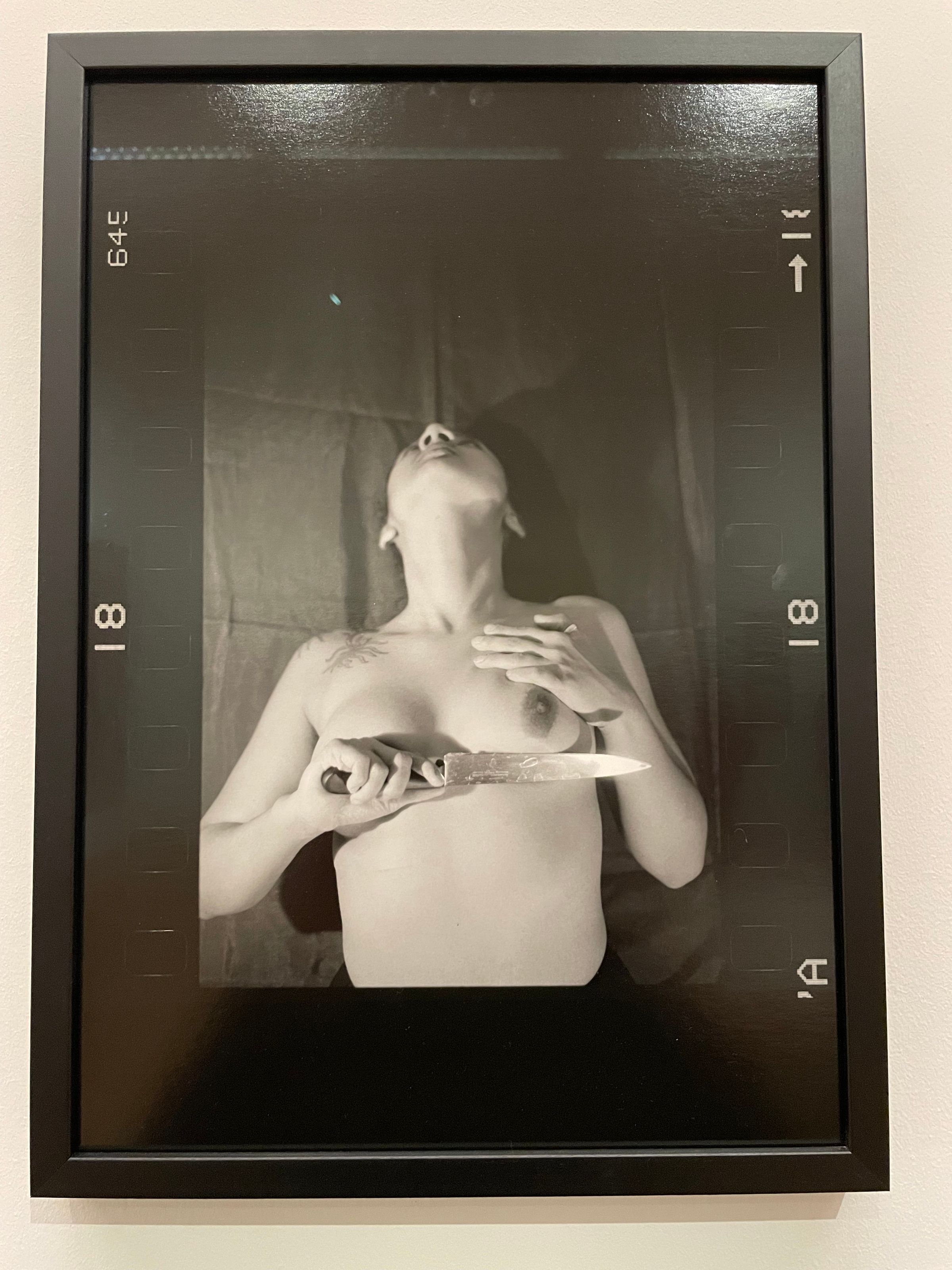

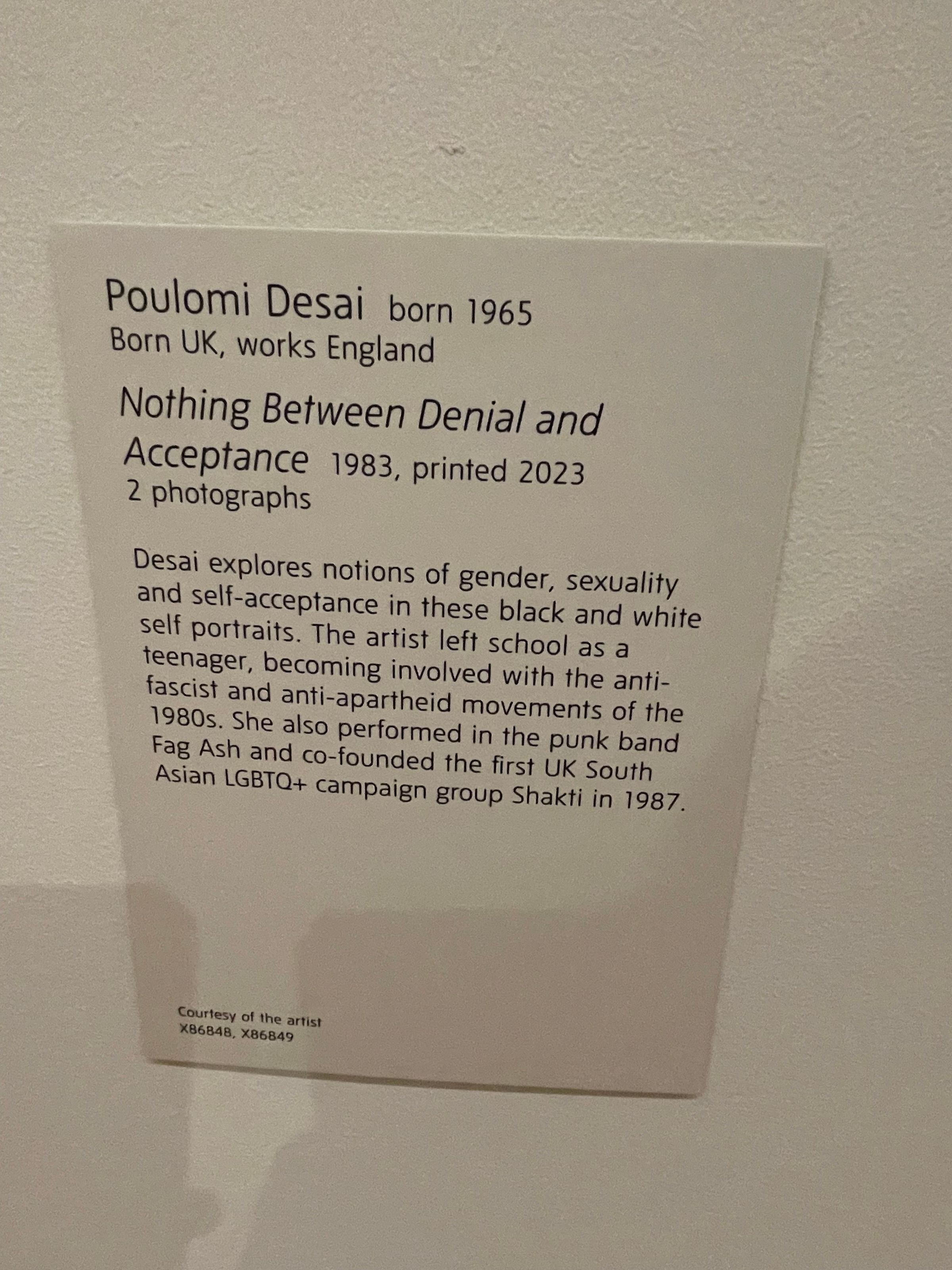

Poulomi Desai, also born in the UK, of Gujarati descent, embraced the post-punk scene in the UK. Defiant, a rebel against India exotica, the self-portrait photographs of her from 1983 reveal an identity that resists her feminine stereotypes, she’s holding a knife against her breast as if she’s about to cut it off. Of course, it’s a performance to camera – she is no doe-eyed teen in a sari or shalwar kameez, aiming to please the male gaze. I will never forget when I first met Poulomi Desai in 1986, a South Asian goth-punk. She opened the doors for me, to a young, angry British Asian arts scene that rejected the samosa politics of multiculturalism.

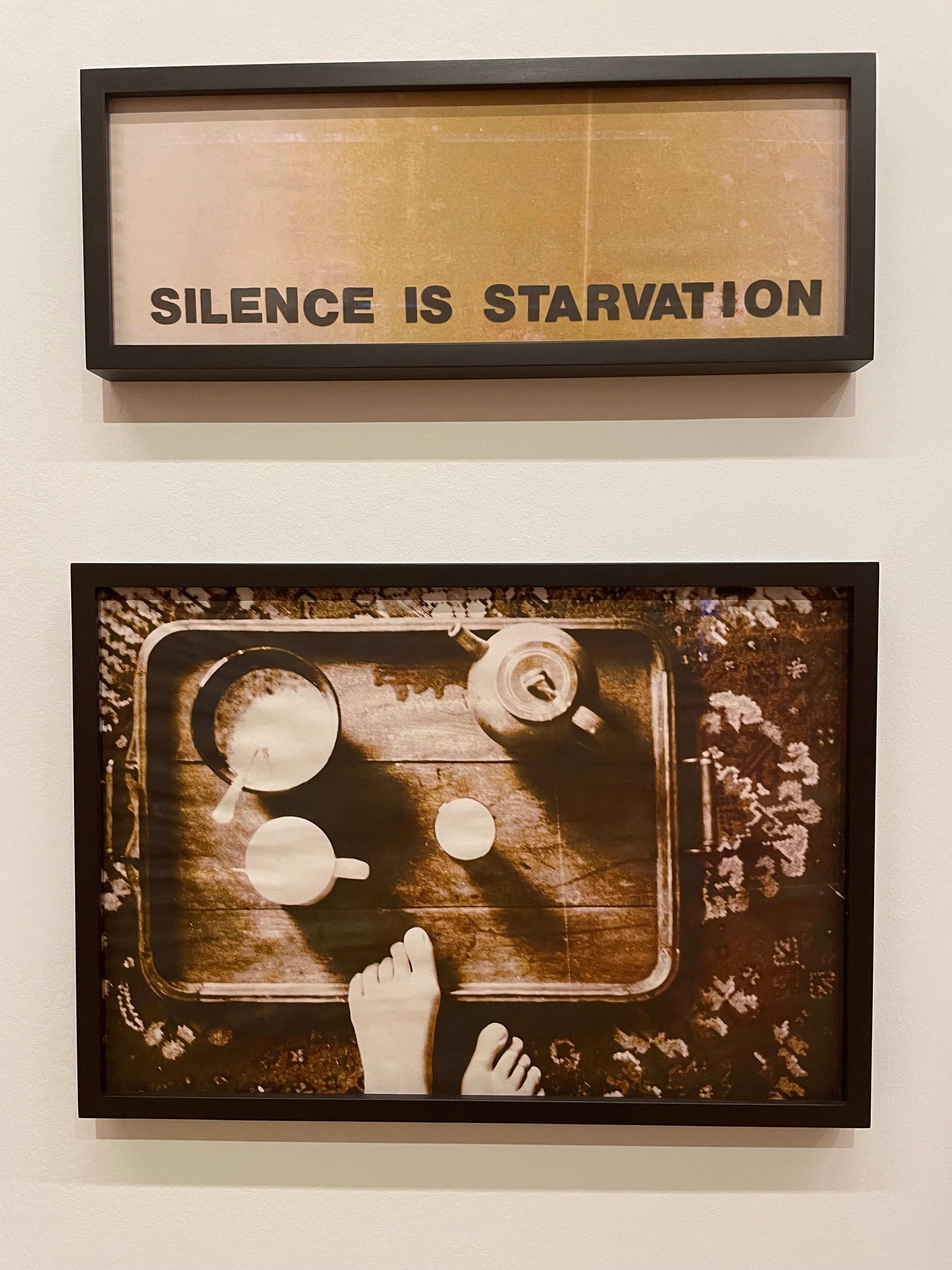

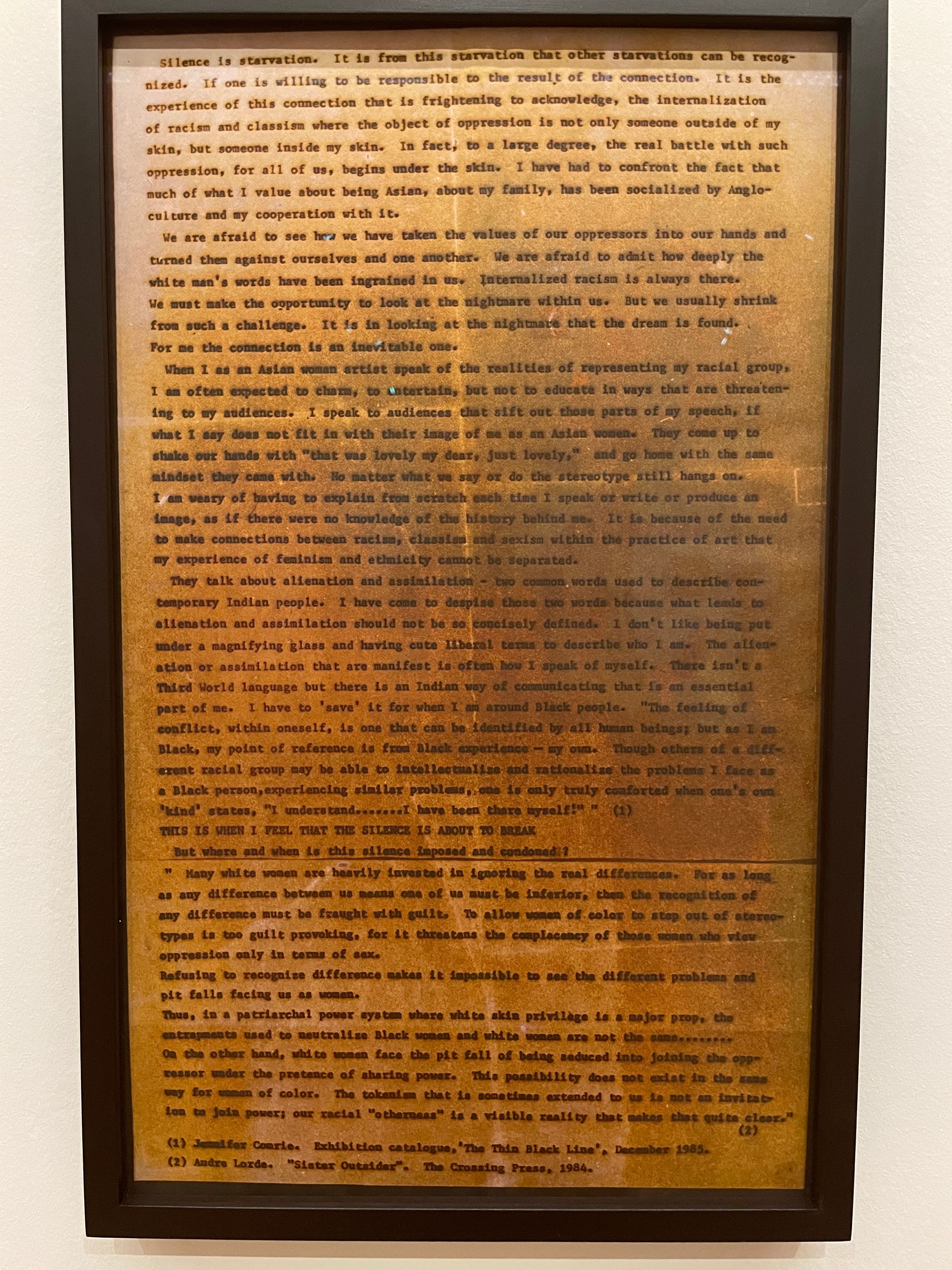

In Response to the F-Stops Exhibition (For the White Feminists), 1987 is an early work by the 2007 Turner Prize shortlisted artist Zarina Bhimji. It displays her ongoing fascination for the still life aesthetic, a poetic approach to the subject of race and feminism, revealed through the texture of light, hues of shade, illuminated objects, the silence enforced by the dominant feminist discourse that fails to see artists of colour beyond the assimilated or alienated duality of identity and representation. The work appears quiet but it’s seething beneath the delicate texture. It is through the long text piece, where Zarina extrapolates the tension of breaking from imposed stereotypical notions of identity politics.

Women in Revolt! Is at Tate Modern until 7 April 2024 then tours to National Galleries Scotland and culminates at the Whitworth, Manchester until 1 June 2025