What makes a woman with a good job, a young daughter and a devoted husband leave all that behind to travel the world promoting a guerrilla cause? Conscience. But it was love (and guilt) that made her come back.

By Wilson da Silva

WE ARE IN CRONULLA, on Sydney’s southern outskirts, where Margherita Tracanelli is taking a break at a friend’s beach house. The water of the bay laps almost to the front lawn, and a catamaran lies abandoned on its side.

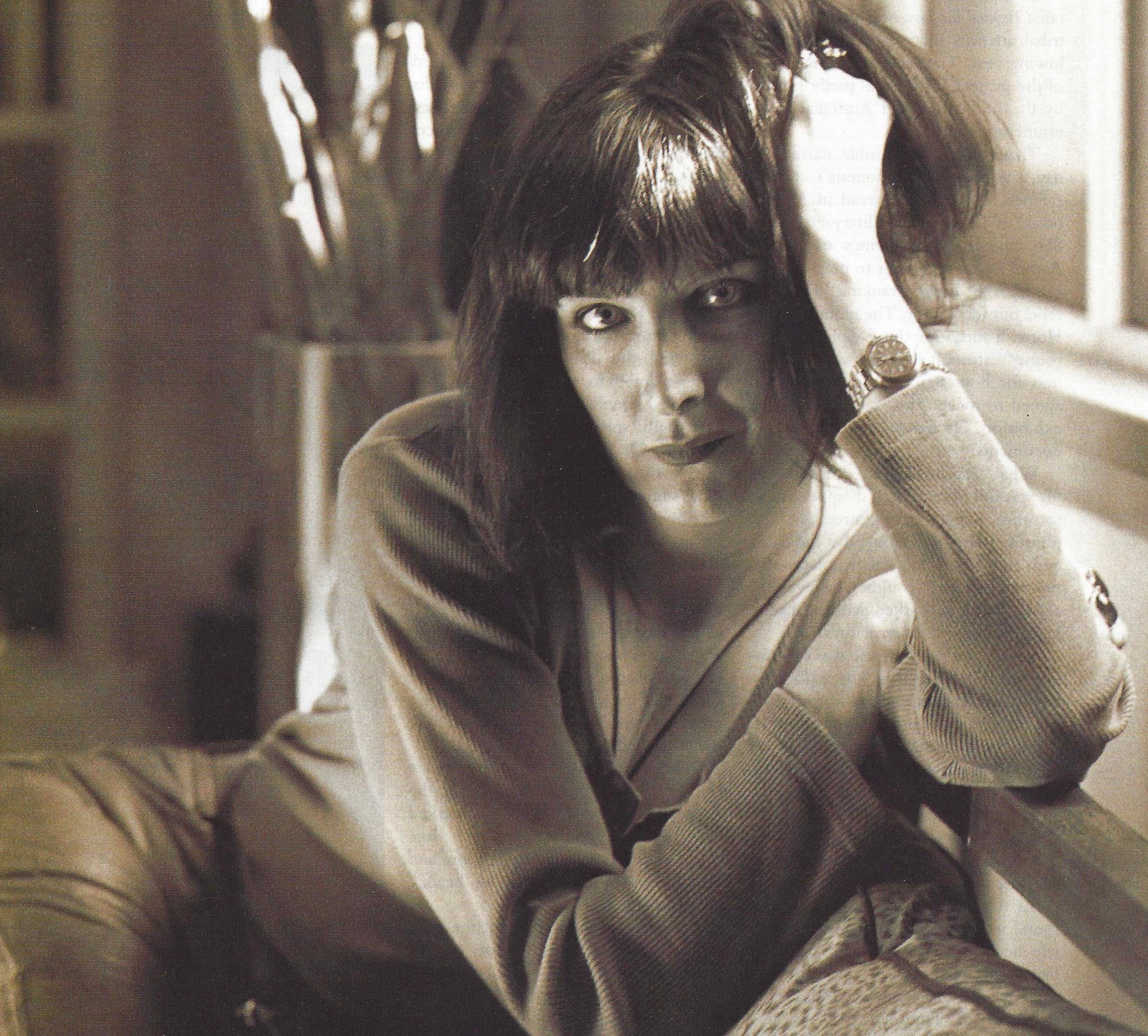

As Tracanelli, a stylish figure in a dark suit, her mouth a bright slash of red lipstick, sips on her glass of wine and leans back on the sofa, it’s hard to credit that this is the woman who for two years put her freedom, her marriage and even her life at risk to work as press attaché to the enigmatic leader of the Timorese resistance movement, José Ramos Horta.

“I’m not a political activist,” says the 37-year-old, running her hands through her hair. “I was a professional person hired to do a job. It just so happened that the job was with the Timorese guerrillas.” She laughs. “I’ve always had a taste for the bizarre.”

The bizarre got a big boost from a quite ordinary place, the Australian Museum in Sydney, where Tracanelli was in her second year as publicist. It was early 1992, and she had earned a reputation for a tell-it-like-it-is approach, one that was welcomed by journalists accustomed to often insincere promotional drivel. It was a style that endeared her to some, but put others’ noses out of joint.

“Different people perceived her differently,” former boss Tone Gibson, public relations manager at the museum, recalls. “Some found her to be abrasive, others admired her qualities, her understanding of the media and how to get a story in the paper.”

“She was a hoot, you couldn’t help but like her,” recalls Susan Bridie, former executive director of the Australian Museum Society and one-time work colleague. “She’s not in the normal mould, definitely a free spirit who does it her own way.”

At the time, East Timor wasn’t on Tracanelli’s radar screen. Like most people, she knew unpleasant things were afoot there: an Indonesian invasion in 1975, reports of human rights abuses, an independence struggle by Fretilin guerrillas, and massacres (including the very recent one in Dili) by Indonesian troops. But it wasn’t until friend and former ABC colleague Mark Aarons launched his co-written book, East Timor: A Western Made Tragedy, in March 1992 that Tracanelli became personally interested.

With good reason. At the time, the museum was preparing the biggest Indonesian cultural exhibition in Australia: Beyond the Java Sea, a collection of tribal artefacts to go on show the following year. Tracanelli was chairperson of the project, which was partly funded by the Indonesian and Australian governments.

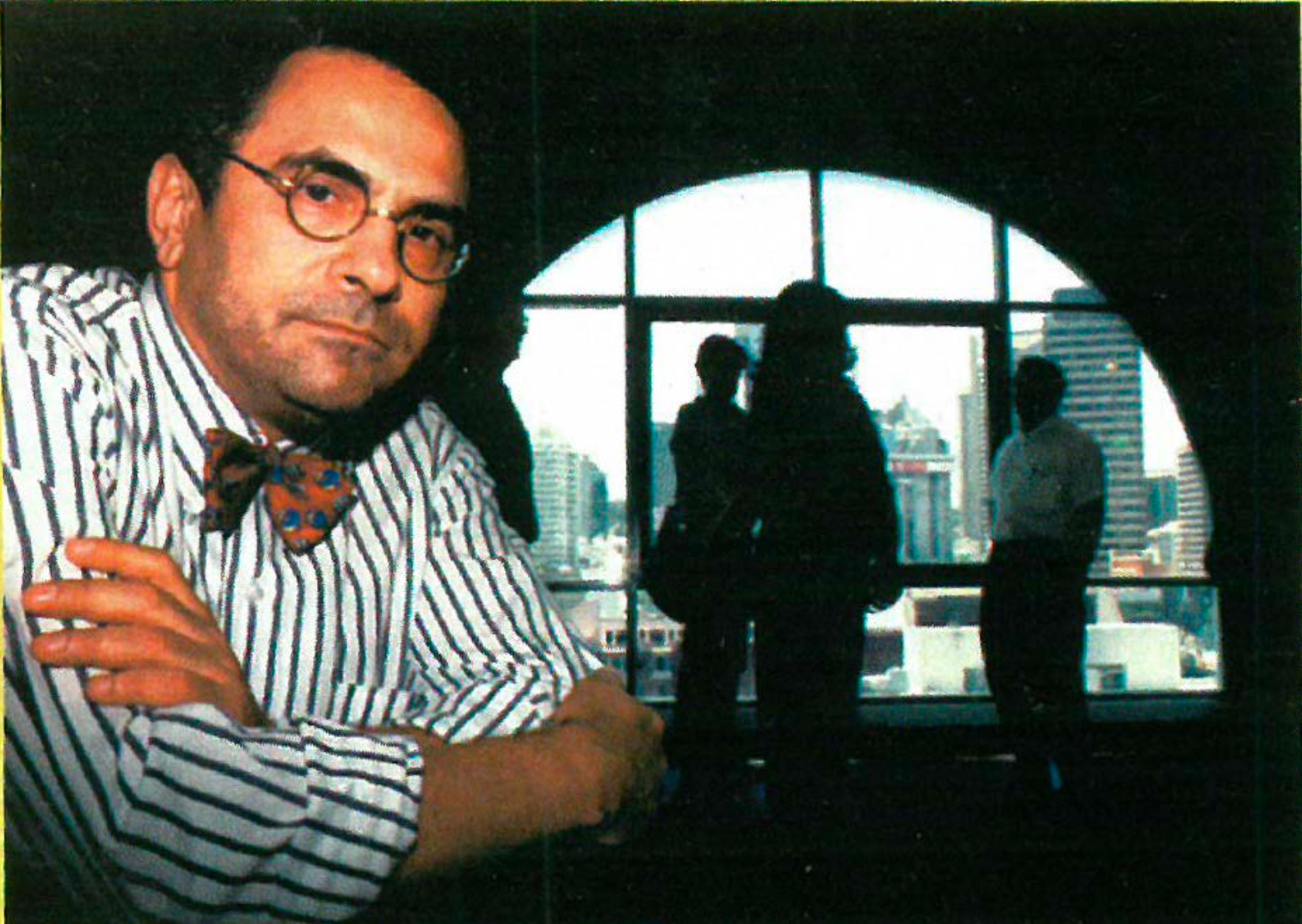

That’s when the trouble started: by day, she promoted Indonesia’s cultural richness; by night, she read in Aarons book of Indonesian military atrocities. She talked her misgivings over with Aarons – he urged her to meet Ramos Horta, the highest-ranking Timorese rebel outside Timor. The globetrotting Ramos Horta, a fortysomething diplomat with round tortoiseshell glasses and a fondness for bowties, was in Sydney and agreed to meet. They talked about the exhibition. He handed her a bundle of documents.

What Tracanelli read shocked her: it was full of reports of disappearances, torture, human rights atrocities and gruesome photos, she says. “I looked at the dates, and this stuff had taken place two months before. I couldn’t believe it. I called Horta and asked why he hadn’t had a press conference about this.”

Before she knew it, she was organising one for him: press kits with photographs, statistics and background on the struggle, helping Ramos Horta write a speech, and faxing the media. On the day, journalists attended in force. Ironically, as Ramos Horta stood to blast Indonesia before the TV cameras, Tracanelli was having tea with Indonesian ambassador at the museum. No one suspected.

As the days went by, Tracanelli found it increasingly difficult to reconcile her work with her conscience. It has been only months since the Dili massacre of November 1991, when hundreds of primary civilians at a funeral march were gunned down by Indonesian troops. She felt the exhibition was slowly being turned into a public relations extravaganza to counteract the bad press Indonesia was copping. She wasn’t the only one at the museum to feel uneasy, but few wanted to make a fuss, and most knew that the then Indonesian ambassador, Sabam Siagian, was friendly with museum management.

Museum officials deny there were any political machinations. Says Jan Barnett, head of community relations there, “It’s not the role of the museum to take sides.” Tracanelli, however, felt the museum was being partisan, and quit as project chairperson.

Days later, Ramos Horta called and offered her a job: running the Timorese media campaign. “From her CV and the way she organised that first press conference, she was obviously the type of person we needed,” Ramos Horta told HQ from Lisbon. “She seemed an able professional and dynamic, and our diplomatic struggle had reached the stage where we needed a professional to deal with the international media.”

The Timorese resistance, flush with donations following the 1991 massacre, wanted to raise the struggle’s media profile. Tracanelli spoke to her husband, Dr David Millikan, a former head of the ABC’s religious affairs unit, acknowledged cult specialist, occasional reporter for Four Corners, and now a minister in the Uniting Church. Long before Tracanelli developed an interest in the Timorese, Millikan had been a strong supporter of the cause. But he warned that it would be a gruelling experience, although he didn’t try to dissuade her.

Friends, in turn, warned the novice activist about burnout, and about the dangers. “I was told, ‘Horta is a marked man. Prepare yourself for the time when you walk into his hotel room and find him with a bullet in his head’,” Tracanelli recalls.

Nevertheless, she accepted the offer to work as media director of the National Council of Maubere Resistance (CNRM), the umbrella Timorese resistance group headed by Ramos Horta. And quit the museum job that she had, until recently, so loved.

MARGHERITA Tracanelli was born in Sydney’s northern beachside suburb of Collaroy to an Italian father and an Anglo-Australian mother. When she was 11, the family left Australia for a new life in Italy. She loved the new country, quickly becoming fluent in the language. It was a strange and exciting place, yet felt like home.

But Italy didn’t work out for the family, and when it came time to return three years later, she was devastated. Back in Australia, she found it impossible to adjust to her old life, and became rebellious at school. At home, her parents fought a lot, and she would lock herself in a room with her brother and sister and try to drown out the shouting with a stereo. At 16 she landed a job as an advertising assistant and left home.

And assortment of jobs followed: sales assistant, Italian interpreter, publicist, independent film producer. She moved to Melbourne to set up a business in the rundown café society of the inner suburbs of Prahan, making TV commercials, corporate videos and documentaries. The work came in, and she made good money.

It was in Melbourne in 1985 that she met Millikan at a dinner party. “It was instant chemistry,” she recalls. But it wasn’t until the following year, when she had moved back to Sydney, there are two really got to know each other.

Millikan had relocated from Melbourne to head up the religious affairs unit at the ABC, and needed a place to live. He moved into a house she shared in the upper-middle class haven of Paddington. Millikan helped her get freelance work at the ABC. It didn’t take long before the two became an item. Millikan’s previous marriage had ended some years before, and she got to know his 15-year-old daughter, Alexandra. Eventually, Tracanelli became pregnant to Millikan, and Héloise was born in 1988. The couple married in 1991.

DAYS AFTER accepting the job with the Timorese rebels, Tracanelli flew to Italy. It was April 1992, and she was to join Ramos Horta in Rome. There, it was straight into the big league. The city was the site for the second round of talks on East Timor between Indonesia and Portugal, chaired by the UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali. Tracanelli had to orchestrate the media campaign and get the Timorese side of the story into the press. Jetlagged, she walked in nearby gardens with Ramos Horta daily as he brought her up to speed. “He told me the history of the struggle, the politics and diplomacy. It was fascinating. I was completely enthralled.

“It felt right, and it felt good. I was very happy, very stimulated by what I was doing. I wasn’t constrained by motherhood or marriage. And I felt for the first time in my life I was really doing a job that meant something. There were people who really needed someone to blow the whistle for them and make a big noise, and I feel powerful, like I could really do that. I would do the very best for them.”

First problem: lack of attention. The Italian media was consumed by a hotly contested referendum. That meant journalists would have little interest in the Timor talks. So, days before her press conference, she visited did every media outlet in Rome, begging them to attend. No snazzy press releases or promises of free drinks. Just direct, personal requests. And it worked: the event was packed. Ramos Horta was quoted around the world, even making it into the newspapers back home, where Millikan read of his wife’s success the next day.

After the talks, the two left for engagements in Geneva, Lisbon and New York. They flew to London as guests of the Australian filmmaker John Pilger, who was then considering a documentary on East Timor (released last year as Death of a Nation). As they travelled from country to country, they occasionally encountered Asian men in badly-cut suits taking their pictures. “It happened all the time,” Tracanelli says, “and it made me feel uneasy.”

In Geneva, she met the correspondent for Vatican Radio, who said to her over a coffee, “What’s a nice girl like you mucking around with these bloody guerrilla rebels and their guns? Why don’t you get yourself a real job?”

She was later told by another Geneva journalist that the Vatican reporter had been one of the many guests on government-paid junkets to Indonesia, to show the world how stable and prosperous the country was. “He had been duchessed,” she says, shaking her head. “He didn’t want to hear anything about atrocities, see video evidence, or anything. I thought this was incredible. I realised there were so few of us with so little money, and we were battling the whole Indonesian PR machine.”

TRACANELLI WAS consumed by the work. By the time she returned to Sydney two months later, it was as if liberating East Timor had become her personal mission. And she had grown close to Ramos Horta. She couldn’t help admiring the hinterland kid who, after decades on the diplomatic circuit, had grown into a smooth sophisticate speaking five languages and who counted among his friends presidents, prime ministers and leading figures like the Dalai Lama.

It all felt very distant from her married self. “It was extremely difficult,” she says. “Bronte seemed very fucking boring. I didn’t want to be here. There was so much work to be done overseas, and I could do so much over there.” There were more trips to Europe to attend UN conferences and to build support among diplomats and the press; two more UN meetings between Indonesia and Portugal, where are little was achieved.

It was a tough time for the Timorese: guerrilla chief Xanana Gusmão have been captured by Indonesian troops in late 1992, and a three month show trial followed. As it drew to a close, Gusmão rose to read out his defence speech, but was cut off after just three minutes when the court ruled his testimony was “irrelevant”. Only days later, however, in what Ramos Horta recalls as one of the duo’s greatest media victories, he and Tracanelli obtained a smuggled copy of Gusmão’s defence while in Washington and leaked it to an international newswire. “We pulled the carpet out from under the Indonesians,” he says. “They were completely fucked up. That was the best moment in years.”

It caused the diplomatic stir, and the Indonesians were incensed. Jakarta boosted the war effort against the guerrillas, and reports of casualties flooded in from the mountains of East Timor. Newly appointed guerrilla leader Ma’huno was captured. Tracanelli received constant stream of resistance reports of new killings and tortures, rapes and disappearances.

As the war raged, she continued to put out a press releases about battles and atrocities, knowing that in some cases, relatives of the victims would suffer reprisals. “There are some strong ethical problems with the work. You know as soon as you publicise atrocities, that it’s going to get worse before it gets better. But you have to keep up the pressure, and you can’t be daunted by that, otherwise you’ll do nothing. You can’t be overpowered or overawed by the enormity of it all. That’s exactly what the Indonesian regime wants you to do.”

By early 1994, the Timorese campaign was showing results – countries, including the US, were banning foreign aid and arm sales to Jakarta, foreign leaders were pressuring Indonesian President Suharto personally, and there were embarrassing incidents like the seven Timorese students who made headlines by occupying the Swedish embassy in Jakarta and demanding political asylum – which they eventually got. But the pressure on Ramos Horta and Tracanelli was enormous. So much expectation and so few resources.

Back in Australia, Millikan was urging his wife to return. And she felt enormously guilty, especially about her daughter. But it was a hothouse political atmosphere and she felt responsible to ‘the struggle’, too.

In June that year, Tracanelli and Ramos Horta arrived in Bangkok to prepare for a meeting of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which Indonesia is a member. On the agenda – embarrass ASEAN and about East Timor, a regional issue ASEAN had been silent about.

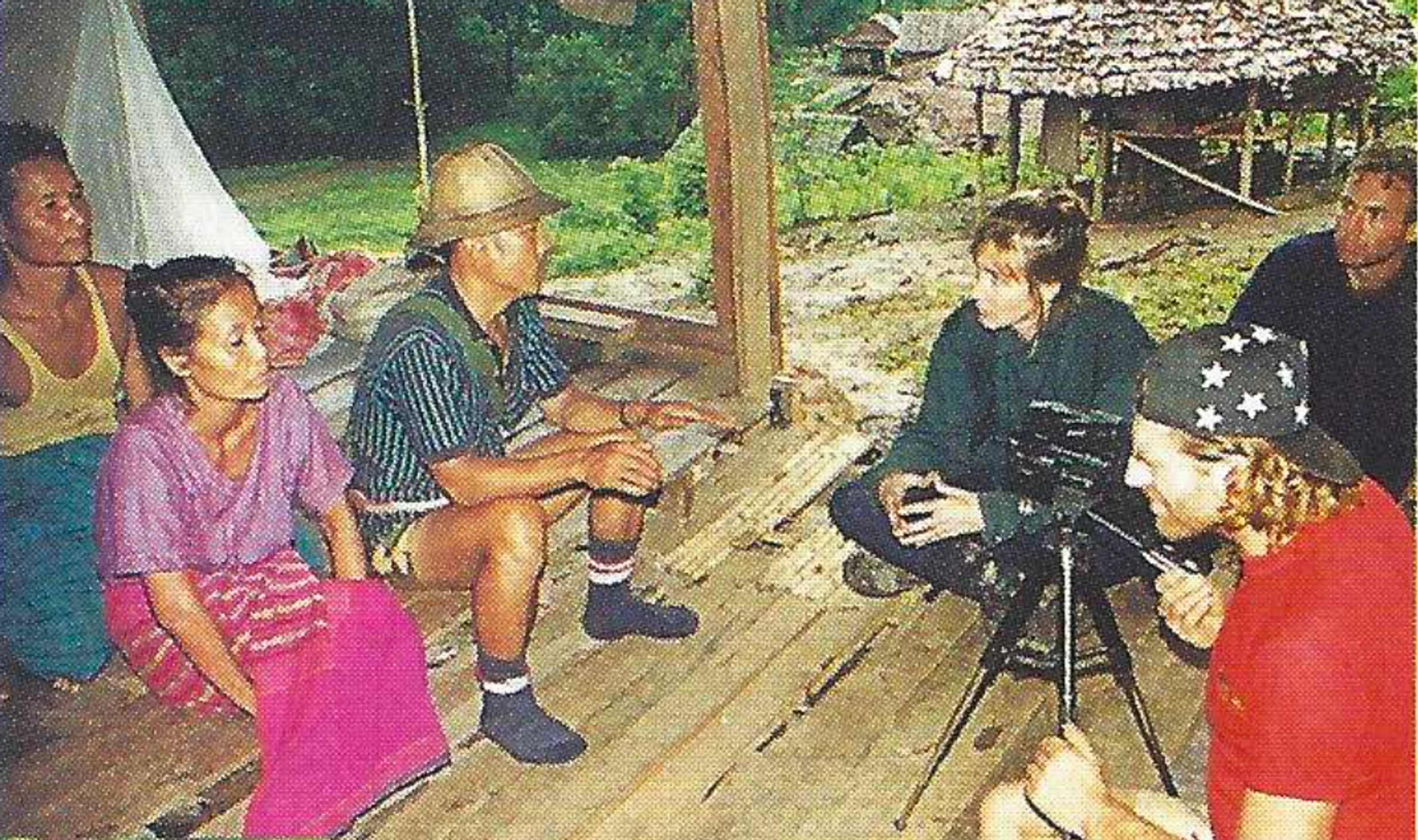

But first, it was over the border to the malaria-infested jungles of upper Burma – not your average holiday spot. They had agreed to teach diplomacy and media skills to the Karen guerrillas fighting the Burmese military government – brothers in arms of sorts for the Timorese resistance. Of course, they would be breaking Thai law by crossing into rebel territory near the town of Mannerplaw. That meant Thai prison if they were caught.

Tracanelli was in her hotel room in Bangkok, preparing to take a 5 am plane to Chiang Mai in northernmost Thailand, and then a boat across the border. “I had a very long shower,” she says. “I just cried and cried and cried, because I realised that going to Mannerplaw was a very dangerous thing. There was cerebral malaria, there was no communication when you’re there, I knew it was a rebel stronghold and parts of the river [on the way there] were controlled by Burmese government soldiers. I also knew two Australian girls have been captured, raped and killed in the area not too long before.

“I asked myself: ‘What are you doing? You have a beautiful five-year-old daughter in Sydney, you’ve got a fantastic husband who loves you to death. What are you doing here?”

They arrived at the guerrilla stronghold after hours of travelling through rainforest and mud. There were elephants bathing themselves in the rivers, and the sound of occasional skirmishers with Burmese soldiers in the vicinity. One night, imprisoned Burmese soldiers broke out of the Karen cells, stole weapons and attacked the camp. Machine-gun and mortar fire awoke her. She went to the concrete paths beneath the tall wooden guest house where they were staying, a room that doubled as a bunker. The battle outside went on for hours and, growing bored, she took a bath.

It was on their return to Bangkok from the Burma mountains that Tracanelli would make headlines. The ASEAN and meeting had started, and Thai officials were on the lookout for troublemakers. They knew she and Ramos Horta were in the country.

Tracanelli attended a Bangkok function one night. Thai police mixed amongst the guests, spotted Tracanelli and approached, asking where Ramos Horta was. She denied knowing him, denied working for the Timorese resistance, and continued to chat with a group of journalists. In truth, she had organised a clandestine press conference for Ramos Horta the next day and had kept the venue secret until the last moment, fearing the Thais would arrest Ramos Horta before he could say a word.

“There was a lot of cat and mouse stuff going on at the time,” Evan Williams, the ABC’s correspondent in Bangkok, told HQ. “The Thais were making it clear they didn’t want José making any public statements in Bangkok that were going to be embarrassing to the Indonesians.” To thwart them, Tracanelli arranged to phone a British correspondent the following morning with the venue, and told other journalist to call him. Meanwhile, Thai authorities searched the city’s hotels for Ramos Horta; but he was safely ensconced in the Portuguese ambassador’s residence.

The next morning, Tracanelli called the British journalist, and Ramos Horta made his way to the venue in a consular car. Just as Tracanelli was packing media kits for the press conference, Thai police knocked on the hotel door. In the room with her was Australian lawyer and activist Frank Coorey, who had gone to Burma to shoot a film, and Filipino photographer and human rights activist Lito Ocampo. There was evidence in the room that they had crossed the Burma border. Coorey and Ocampo went outside to argue with the Thais, stalling while Tracanelli stuffed films and 8 mm videotapes into her bra and underpants. Just in time, too. The police were polite, but wouldn’t be stalled for long, and the three were eventually led away to be interrogated. Tracanelli slipped a message to the hotel desk that she had been arrested.

At the police building, Ocampo – well known to the Thais as an activist – was put in jail, and she and Coorey were interrogated. She was terrified they would stop Ramos Horta’s press conference, or search her and find the films. So she refused to speak English and produced her Italian passport, obtained years before. She demanded Italian consular representation – more stalling. When the representative arrived , the interrogation was conducted in Italian, the consulate official translating into Thai. The police wanted her to sign a confession that she had broken the law and gone to Burma, and was involved in resistance activities. They wanted to deport the three. But they were happy to put them in jail if they didn’t sign.

“The Thais threw a whole lot of intelligence on the table at me, because they were getting very frustrated, and said, ‘You’ve been here before. You work for Horta. You have a bank account in Chiang Mai. You cross river to Burma.’ I said, ‘Listen, that’s an entry visa for Horta, not for me’ – although I did enter the country the same day, they produced the wrong one. I said I changed money in Chiang Mai, but I didn’t have a bank account there. I said their intelligence was wrong, I had not gone to Burma.”

Meanwhile, the press conference went ahead, where Ramos Horta announced Tracanelli had been arrested. Later, Ramos Horta phoned around Bangkok trying to find her. “I was very worried for her safety,” he recalls. “When I finally tracked her down … she sounded completely in control. What impressed me was that, while in detention, she was worried about whether the journalists had turned up to the press conference.”

Ramos Horta advised against provoking the police into throwing her in jail as a publicity stunt. It was not safe. It was best to comply with their demands and leave the country, he said. Sensing the Thai’s patience was at an end, and to avoid a search, Tracanelli acceded on condition they release Ocampo. They agreed. The confessions were signed

A flight for Sydney was to depart early the next morning. Tracanelli sneaked a moment alone in the transit lounge that night to call the ABC’s Williams, who taped an interview. Next morning, as she and Coorey boarded the plane for home, it was broadcast in Australia on the influential ABC current affairs radio program AM. That same day, reports of Ramos Horta’s clandestine press conference and Tracanelli’s arrest made headlines across Asia and Europe. In Thailand and the Philippines, pictures of Ramos Horta were splashed across front pages. By the time Tracanelli arrived in Sydney, a throng of reporters were waiting. She should have been weary. Instead she was bright-eyed and fiery before the TV cameras, damning ASEAN for its lack of courage.

She then rushed to the Gore Hill centre of ABC TV in Sydney, where the newsagency Reuters has a studio. She had a video with a personal appeal from the Karen leader general Bomya to the ASEAN ministers still meeting in Bangkok. The footage was beamed out to television stations around the world, and appeared on Thai TV the next day.

It was a public relations disaster for the Thai government, and an embarrassment for ASEAN. “They were pissed off, there’s no doubt about it,” says Williams. “That was really an embarrassing thing for the Thais diplomatically, to have this happening at the same time you’ve got Indonesia there and the ASEAN foreign ministers.”

Back in Bronte again, with the winter sun in her face and Héloise on her lap, Tracanelli knew that she had to make a decision about the future. “I felt I didn’t want to be here. I was in a world of my own,” she recalls. “I loved my husband and I loved my child, and I never wanted to give them up and I would never leave them. But I felt like I found something that could really use me, and this was a really worthwhile and a very important thing. I felt responsible for Horta too … he and the whole Timor thing had me in an emotional grip. I was tremendously confused.

“When you’re working at that fever pitch, in a hot political environment, dealing with the resistance in East Timor, with a guerrilla group in the mountains, operating with no money and with an exiled Timorese community all over the world that is so fractured and traumatised – it’s very, very hard. You start losing perspective.”

It was August 1994. The diplomatic war for East Timor was shifting to the US Congress and the European parliament. To continue the work, Tracanelli would have to move to Europe, learn French and Portuguese. And that meant leaving her family. “I had to choose either Horta and the resistance, or my family. It was one or the other,” she says. “And I wasn’t prepared to do that … I couldn’t be split from my family any longer. I felt it was wrong of me, to have a child and a husband and just basically abandon them. I had to stay. It was time to be home.”

In some ways, quitting was the most difficult decision. But also, the most obvious. She finally left in November last year: Ramos Horta has nothing but praise for her work. They still correspond, and every now and then, he sends a chatty postcard to Héloise from some corner of the world.

It was the most stimulating time of her life. But it also cost her dearly in personal terms, something she blames on no-one but herself. “David and I are really strong now, we’ve got a marriage that is rock solid. But we’ve been to hell and back.”

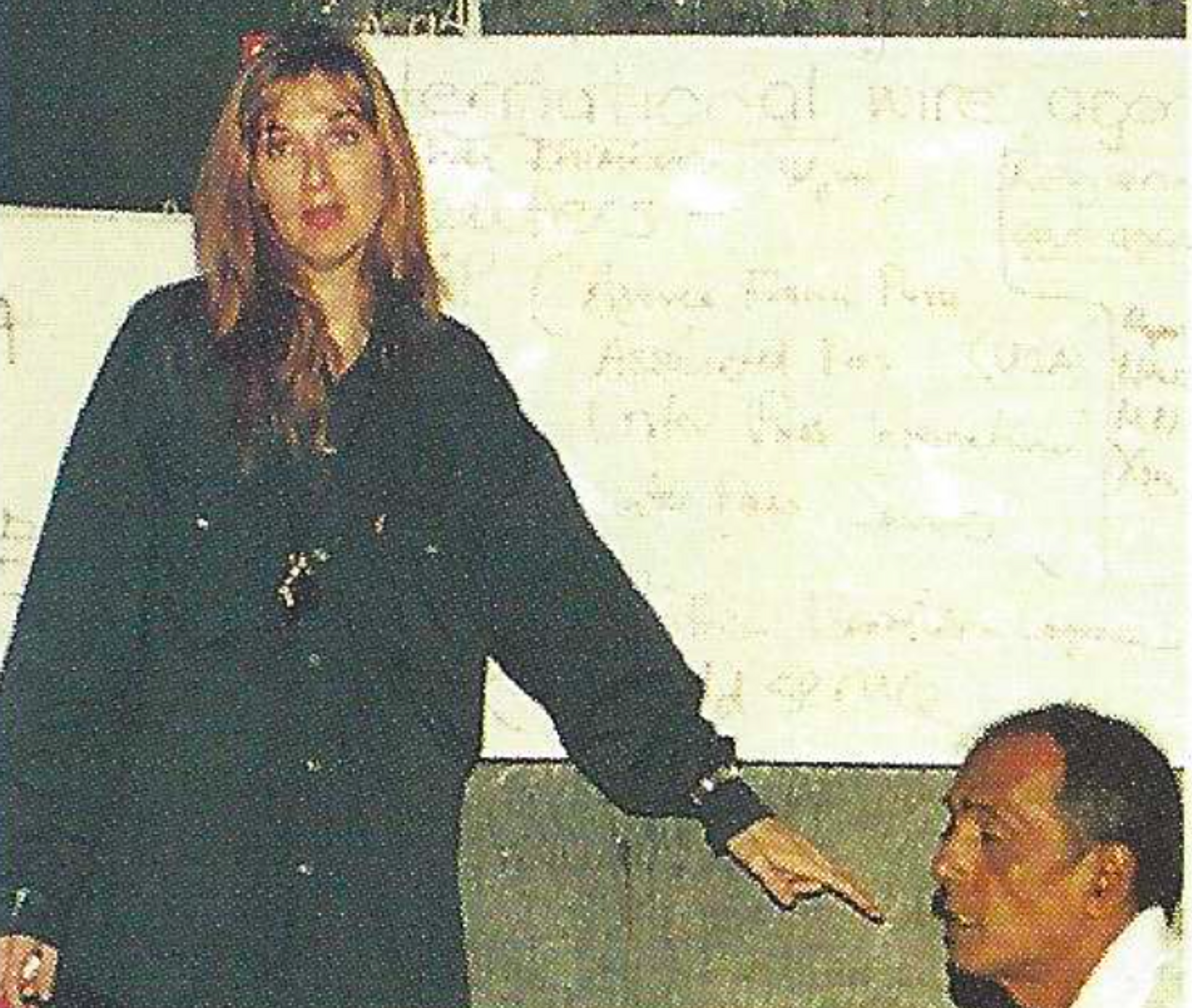

What of the future? In between learning Thai and doing the odd bit of public relations consulting, she is developing a training course for human rights workers and non-government organisations which, with funding from development programs, she hopes to start taking to Asia next year. She’ll rely on her Timor contacts. But there’s no going back, no matter how attractive. “If I had been a single person, without a doubt, I would have done it,” she says. “I would have pursued it, I would have stayed with it. And I still be doing it. It was interesting as hell, damn it.”