By Wilson da Silva

HOW MANY SCIENTISTS can be called a superstar, or even a celebrity? Not that many.

We wildly laud and respect our sportsmen and women, the brave veterans of past conflicts and even political leaders – well, the latter have more visibility than adulation, perhaps. But, as a rule, we don’t put on tickertape parades for our scientists, no matter how amazing the feats they may have performed in the line of duty.

This is a common complaint, and one espoused before by Frank Sartor, the Minister for Science and Medical Research in New South Wales, and most recently by John Howard, Australia’s Prime Minister. “I look to the day when the exploits of Australian scientists will be as revered and remarked about as the exploits of our sportsmen and women,” Howard told a gathering at Canberra’s Parliament House in October 2005.

He was speaking to an audience of Australia’s most eminent scientists who were attending a ceremony to honour the winners of the Prime Minister’s Prizes for Science. There are five awards in all, and at a fancy dinner in tuxedos and ball gowns at the Great Hall every year, science is given centre stage for a night.

This year, the ceremony was held on an auspicious day for Australia: the day the nation awoke to discover that Sweden’s Karolinska Institute had chosen two of its countrymen as winners of the Nobel prize for Physiology or Medicine: Barry Marshall and Robin Warren of Perth.

Australians don’t feature heavily in the long list of Nobel prize-winners: the country claimed just six Nobel laureates before 2005, the last being Peter Doherty in 1996 (who won in the same category). Marshall and Warren make it eight, or an average of one prize every 13 years.

Marshall was able to fly into Canberra for the event at short notice, and spoke before the gathering. He was given a standing ovation – which is understandable, given that Marshall was playing to his peers. But it was still a relatively rare sight to see in Australia: people spontaneously standing and clapping for a scientist.

While some of us might wish that the achievements of science were somewhat better recognised, and that we celebrated our best and brightest with at least some of the zeal we do cricketers and film stars, the truth is, that will probably never happen.

Most of Western society seems inured to science, and strangely disconnected from it. Society largely sees science as separate from daily life – at exactly a point in history when scientific advances affect our lives the most, and determine our futures.

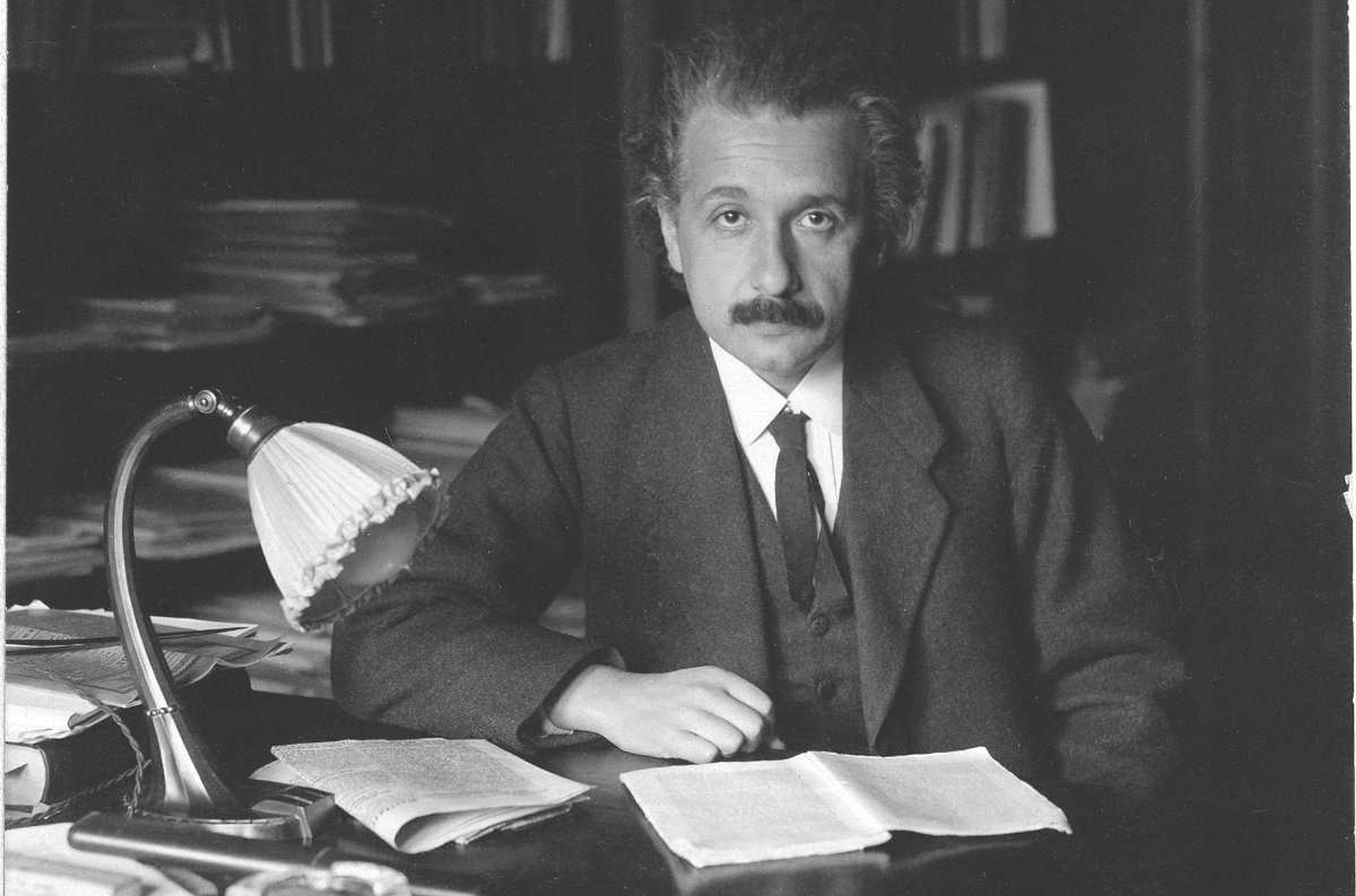

There was one man who broke through this disconnect, and that was Albert Einstein. No other scientist in history has had as much impact, nor gained as much visibility and public adulation as the German-born son of a Jewish featherbed salesman. Not only is he considered the most influential scientist of the 20th century, he was named by Time magazine the ‘person on the century’.

You could hardly think of a more unlikely candidate: a theoretical physicist with a thick German accent famed for an obscure theory that most people still find difficult to comprehend. Many people can name his most famous equation, E=mc², but few know what it means.

He was the first – and possibly the last – celebrity scientist.

Einstein’s impact was undeniably profound, and his popularity was as widespread and genuine as it was puzzling. People mobbed him in the street and wrote heartfelt letters in their thousands. Such was his effect that he remains today the iconic figure of science, influencing films, books and television so long after his death.

It was 100 years ago that Einstein had his miracle year, publishing five scientific papers that made significant advances in a number of fields. It’s because of this amazing feat, at the age of 26, that 2005 is celebrated as the International Year of Physics, or ‘Einstein Year’.

It would be exciting to think that somewhere in the world, another 26-year-old might today be sitting down to write a scientific paper that will similarly shake our world, perhaps annihilating old theories and breeding whole new fields of science.

It’s how science moves forward: sometimes in short steps, sometimes in jarring leaps.