The microchip that spawned the personal computer revolution is 25 years old next week. And the revolution is not over yet, WILSON da SILVA forecasts.

THE world changed for- ever on November 15, 1971. And hardly anyone noticed. Watergate was still seven months away. John Newcombe and Evonne Goolagong had won at Wimbledon. Yet on that morning 25 years ago, a small start-up company in California known as Intel, barely three years old, put out a press release that signalled the dawn of the Digital Age. “Announcing a new era in integrated electronics,” it said breathlessly. And for once, it was an understatement.

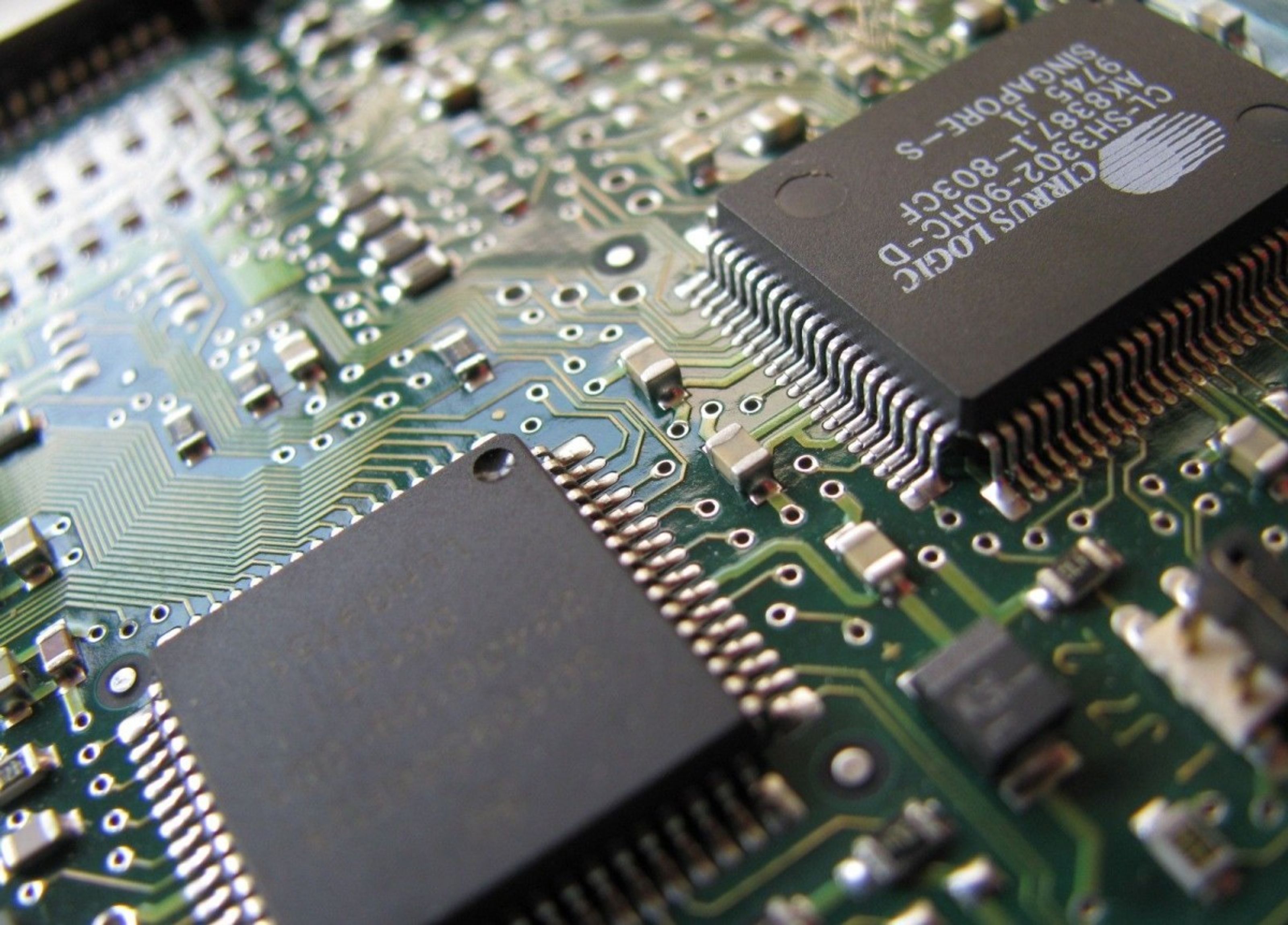

The product launched was the Intel 4004, the first general-purpose “microprocessor”. It was an innocuous sliver of silicon in a dark metal casing with fat metal electrodes for legs, looking all the world like a headless electronic cockroach. With 2,300 transistors, it could process what must have seemed like an astounding 60,000 instructions a second. In today’s tech-talk, it was a 4-bit microprocessor with an operating speed of 100,000 cycles, or 0.1 megahertz (MHz). It cost $US200 ($250) or, in today’s terms, $US3,330 per MIPS (million instructions per second).

In 1971, offices were filled with paper: order books and invoice folders, carbon copies and suspender files and forms in triplicate. Today, the office is a more contemplative place; the army of clerks has been replaced by a platoon of skilled information workers or - as the US Labor Secretary, economist and author Robert Reich describes modern workers - “symbolic analysts”.

Today, that little-known company in Santa Clara, California, is the world’s largest manufacturer of microprocessors, with 42,000 employees and annual revenue of $US16.2 billion.

Intel’s latest chips, the Pentium and Pentium Pro, all trace their lineage back to the 4004. The high-end Pentium Pro chip has 5.5 million transistors, a clock speed of up to 200 MHz, and can process 381 million instructions per second.

“None of us thought it was going to be this big,” Albert Yu, senior vice-president at Intel, said. “We thought it would be substantial, we thought it had potential. But we had no idea it would go this far.”

When the 4004 chip hit the market, IBM was making big, heavy, room-crowding mainframe computers. The arrival of the 4004 made hardly a wave: the reaction from industry to Intel’s innovation was, largely: “So what?”

Two years earlier, in 1969, two Intel engineers, Ted Hoff and Federico Faggin, had created a working CPU, or central processing unit - the heart of today’s personal computers - under licence for a Japanese client, Busicom. Hoff persuaded Intel to buy back the rights to the chip. Nobody realised at the time it would be the deal of the century.

After the birth of the Intel 4004, nothing much happened at first. In the year that followed, more US astronauts walked on the moon from Apollo 16, Tom Kenneally published The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith and Gough Whitlam took the Lodge.

That same year - 1972 - Intel launched the 8008 chip - an eight-bit microprocessor with 16,000 bytes, or 16KB, of memory. It could process 300,000 instructions per second - a five-fold improvement on the year before.

It was a confirmation of “Moore’s Law”. In 1965, before founding Intel, Gordon Moore had stated that the number of transistors that could be crammed into a chip would double every 18 months.

Over the next five years, the personal computer industry was born. The Altair, the world’s first PC, persuaded two young men, Bill Gates and Paul Allen, to abandon their first computer company, Traf-O-Data, in favour of founding Micro-Soft , which supplied an operating system for Altair. Apple came on the scene, and many of the traditional computer systems suppliers - Digital and Xerox to name just two - dabbled in PC technology. But generally their efforts came to nothing because senior management could not get to grips with the disciplines of new world.

With the arrival of a spreadsheet called Visicalc, everyone saw for the first time what computers might do - instant calculations. Figures altered on a budget spreadsheet, for example, would automatically flow on changes to other parts of the document and update them.

By 1980, the personal computer industry was becoming too big to ignore. IBM, scared into the market, created a crack unit of engineers in August 1980 to develop its own personal computer. When the IBM PC was launched in August 1981, it single-handedly legitimised the personal computer as a serious tool. It sold like hotcakes.

By January, 1983, the revolution was so apparent that Time magazine named the personal computer “Man of the Year”.

Now, at the close of the century, more PCs are manufactured than televisions. Yet there’s more ahead.

“Moore’s Law looks like it’s going to continue,” Albert Yu, a 20-year veteran with Intel, said recently. “I certainly don’t see any physical limits ... looking out to the next 10 years or so.

“Today, there’s close to 6 million transistors on a Pentium Pro chip. If you draw a straight line, you can imagine anywhere from 300 to 400 million transistors 10 years out. Just imagine the kind of power that will be available by that time.”

DAVID HILL: Marketing director for smartcards, Motorola Australia

“THE impact hasn’t really started yet. Today’s motor vehicles have an average of 20 microprocessors. By 2000, that will get to 35. In the office, there’s an average of 18 today. By 2000, that will be 42. The biggest jump will be in the household, where today there are 69 microprocessors; by 2000, there will be 226. In the 1960s, one transistor on a microchip was worth 15 cents. On Motorola’s newest PowerPC chip, the cost of a transistor is four-millionths of a cent. The core of almost all technologies is the microprocessor or microcontroller. The smartcard is the one microprocessor that’s really going to change the world. Under the gold area of the smartcard is a microcontroller containing information specific to the user. It has lots of special security features inside the silicon so that it cannot be tampered with. In 10 years’ time people’s wallets will be full of smartcards, for loyalty schemes and financial services and eventually government and health services, too.”

IAN PENMAN, Managing director, Compaq Australia

“THE early 1970s, the birthtime of the Intel processor family, was a watershed in national and international history. The Vietnam War was drawing to an end with a great loss of innocence. The most significant technology change Australians were about to experience was the dramatic impact of colour television. The birth of the Intel processor family at this time was overshadowed by these happenings, yet its global impact may one day be perceived to have been more pervasive. For 25 years, the Intel microprocessor has fueled a revolution that has taken computing from quarantined, high-security corporate dungeons to ordinary suburban living rooms. Along the way we have seen the demolition of the walls of the proprietary computing architectures and the empowerment of a global mass market. To be fair, these are not the achievements of Intel alone, but of a group of technology leaders operating sometimes in partnership, other times in competition, but always in synergy; companies such as Microsoft, Novell, Oracle, Compaq and many more ... today, computers with a level of power once used exclusively by government, large corporations and universities now fit into the average family budget. Intel’s contribution to advancing technologies has helped realise the vision of powerful computing in every home and continues to impact the lives of millions of people worldwide every day.”

BOB SAVAGE, Managing director, IBM Australia

“WHEN IBM and Intel got together to build the first IBM PC, neither of us could have predicted the huge impact it has had on the way people throughout the world work and play - driven largely by open standards and equal access for all. Making technology accessible should continue to be a priority for industry leaders. This will be particularly important as networked computing and the Internet are increasingly delivering global and instant access to data for millions of people worldwide.”