THE WEEKEND AUSTRALIAN MAGAZINE

It began with a hurried flight on a small, chartered twin-engine Cessna from Dili to Darwin on December 4, 1975. It ended with another flight, this time on a white United Nations Hercules that left from Darwin to Dili almost exactly 24 years later.

By Wilson da Silva

DECEMBER 1, 1999: José Ramos Horta, Nobel Peace laureate and East Timor’s chief campaigner abroad, was finally ending a life in exile. It was a flight that had been a long time coming. Although the distance from Darwin to Dili is a mere 400 miles, it was a distance that, for half his life was an impossible gulf to traverse.

Ramos Horta was 25 when he left East Timor on that December morning almost a quarter of a century ago. He had been sent on an urgent mission to the United Nations, to bring the world’s attention to what was a widely-expected Indonesian invasion of the small Indian Ocean half-island that, for half a millennium, had been a sleepy backwater Portuguese colony.

Fearful of the looming invasion, and with Portugal seemingly disinterested in the fate of her colony, his colleagues in the left-wing Fretilin political party had declared unilateral independence six days earlier, creating the Democratic Republic of East Timor. Ramos Horta was in Darwin that Friday and was caught unawares, on his way back to Dili after a frenetic but largely unsuccessful lobbying campaign of foreign embassies in Canberra. When he returned the next day, he discovered he had been made foreign minister and ordered to New York to raise the alarm.

But by the time his plane touched down in Lisbon on the way to New York, Indonesian paratroopers had already descended on Dili. Hundreds lay dead along the tree-lined beachside promenade that is Dili’s main street. Ramos Horta knew none of this until he was greeted at the airport of the capital of the faltering Portuguese empire by Armando, an uncle he had heard about but never met. “The sons of bitches have invaded,” he told the young man through tears of grief and disbelief.

Three days after the invasion had begun, Ramos Horta arrived at John F. Kennedy airport on a cold winter’s day. He was met by a driver from the embassy of Guinea-Bissau, a small and newly-independent African country that had also been a Portuguese colony and had offered help.

“I had never seen snow in my life, except in Christmas cards,” Ramos Horta recalls. “He took us to our hotel room and checked the locks, closed the door and tried to force it open, checked the windows, looked outside, under the beds to make sure there were no wires or bombs. This was my welcome to New York.”

Portugal had taken an interest too late, and broke off diplomatic relations with Indonesia. It called for an urgent debate in the Security Council, backed by Guinea-Bissau and a clutch of former Portuguese colonies in Africa. As far as the United Nations was concerned, East Timor was still a ‘non-self-governing territory’ under Portuguese administration, as it prefers to refer to colonies.

Ramos Horta was summoned to address the United Nations Security Council. He picked his way through the unfamiliar snow, negotiated his way through the New York subway system to arrive at the imposing United Nations building on the East River. “I was probably the youngest and most naive foreign minister ever appointed anywhere.”

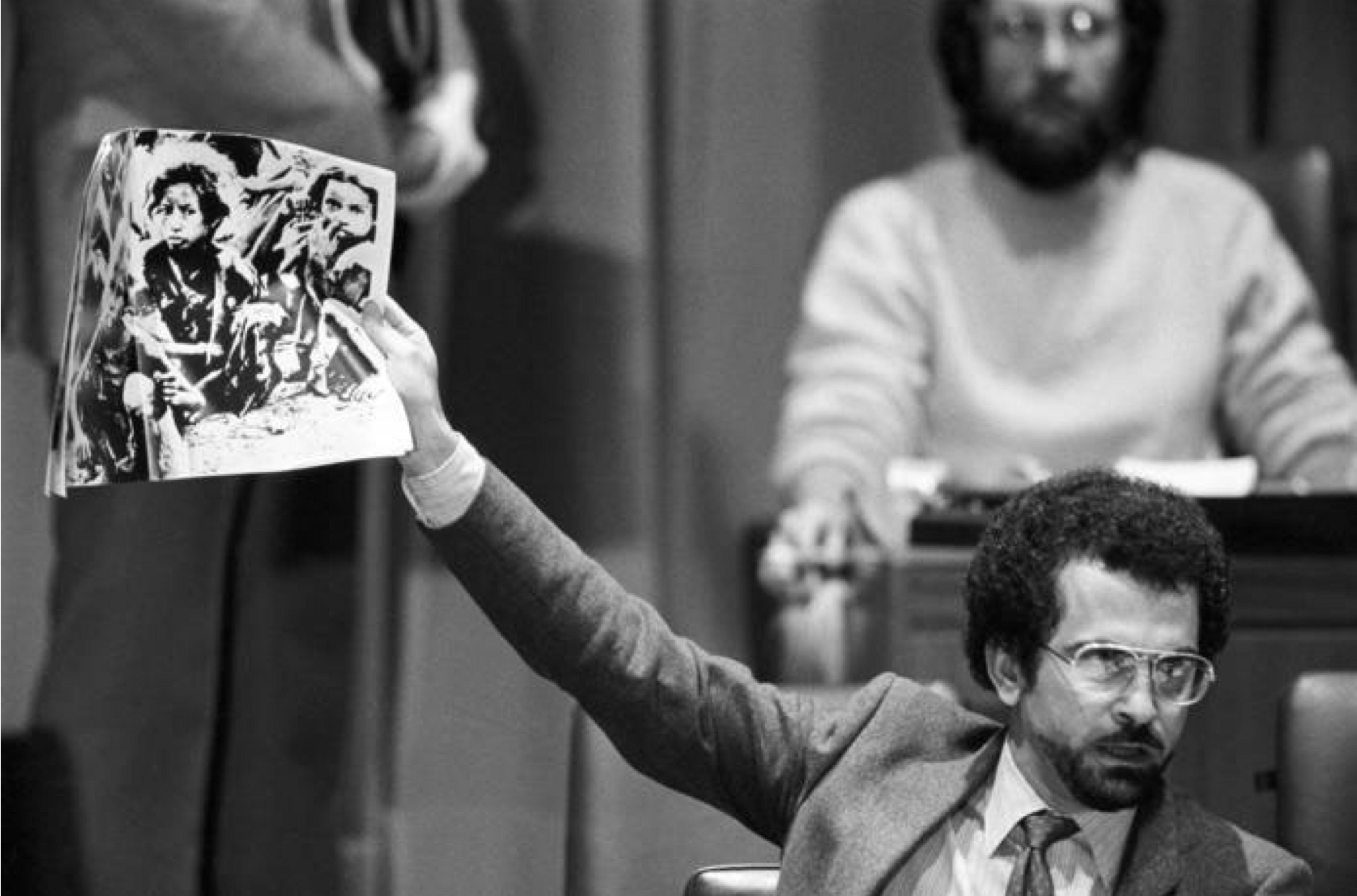

Despairing for the fate of his small nation of 650,000 people, but sensing an opportunity, the nervous Ramos Horta, with a borrowed jacket and an enormous Afro hairdo, read haltingly from a prepared statement as the 15 ambassadors on the semi-circular table of the Security Council looked on. “This council must call upon the government of Indonesia to withdraw immediately and unconditionally all its forces from the territory,” he demanded.

As the debated ensued, Ramos Horta grew more optimistic. “I was shy, intimidated, excited, euphoric and fearful. The transition from East Timor to corridors of power of the U.N. couldn’t have been more dramatic. But it was obvious to all that the invasion of East Timor was a clear breach of the U.N. Charter.

Despite Indonesia’s spurious arguments to justify its intervention and its strenuous efforts to block the decision by the Council, a rare unanimous resolution was reached by December 22. This occurred in the middle of the Cold War … On the face of it, such a unanimous decision was remarkable.”

Ramos Horta was ecstatic. At 25, the youngest person to take part in a Security Council meeting, he held in his hands resolution affirming the right of the Timorese to self-determination and calling on Indonesia to withdraw its troops “without delay”. He had left Dili promising to return in a few weeks. Now it seemed he might, armed with a Security Council resolution that would force Indonesia to retreat.

But nothing happened. “That was the year that my schooling in international hypocrisy began. It was just another Security Council resolution that no-one had the stomach to pursue,” Ramos Horta recalls.

Christmas came and, with it, word that the Indonesians had taken Dili, albeit with heavy casualties. East Timor’s Falintil fighters had withdrawn when the Indonesian contingent in Dili reached 10,000, at a time when Falintil had a mere 3,000 men under arms. Ramos Horta worried about the welfare of his mother Natalina and his siblings, whom he knew to have escaped to the mountains, as had two-thirds of the country’s population.

The following year he heard that his youngest and dearest sister, Mariazinha, had been torn apart by a shrapnel bomb – dropped by one of the Bronco aircraft hurriedly sold to Indonesia that same year by the United States. He still has a framed photograph of his sister in the prime of her youth. “American democracy at work,” he quips sarcastically.

For three years, Indonesian casualties mounted as the Timorese resistance to the invasion proved stiffer than expected. Indonesia poured military hardware into the campaign, and an estimated 200,000 Timorese died either directly or indirectly – almost a third of the population. His brothers, Gui and Nino had joined Falintil and, as he would later hear, were killed in combat.

“They were the darkest years of our struggle,” Ramos Horta says. “That’s when the largest massacres took place, when literally tens of thousands of people died like flies – of massacres, of hunger, fleeing bombardments, military onslaughts and encirclement, unable to cultivate the land. These were years when I thought, you know, we were defeated. The odds were so great that I thought we were being deleted from history.”

East Timor was a closed territory and little news got out, although refugees were sporadically streaming out to Darwin, to Lisbon and to former Portuguese colonies in Africa like Mozambique, which offered the Timorese leadership asylum. It was here that the exiled representatives of the Democratic Republic of East Timor, a nation barely nine days old before it was snuffed out, made their temporary base.

It was here that Ramos Horta met and married Ana Pessoa, a 21-year-old Timorese law student and left-wing firebrand who had been in Lisbon at the time of the invasion. A member of Fretilin, she joined the small contingent of 30 or so compatriots in Mozambique to help plan their future political struggle.

“We had a ceremony before our colleagues at the Fretilin mission in Mozambique,” recalls Ana, now a law professor in Mozambique and a senior official in Fretilin. “The celebrant read from the book, and we said yes, we want to marry. We didn’t even have wedding rings!” She bore him a son, Loro; the child was stricken with severe glaucoma from birth, requiring repeated surgery.

The shattered resistance leadership decided to send Ramos Horta back to New York to begin the long campaign of winning world support for the cause of East Timor. There was little money: whatever working exiles could scrape together to donate, or the occasional handout from a friendly government, church group or non-government organisation.

Ramos Horta set himself up in a small, cockroach-infested Manhattan apartment near 2nd Avenue. He worked nights as a security guard for a private school and glad-handed diplomats at the United Nations during the day, sending part of the money to Mozambique for his baby son.

“I was probably the most irrelevant person walking around New York at that time,” Ramos Horta says. “I could have walked away. But never once I lost hope. Never once I thought of quitting altogether.”

He stayed 13 years before moving to Australia, dodging bill collectors and scrapping together enough to get by. “He was very often ill,” says Ana. “There were days when he would eat just the once. I was in New York for a month once, and … I saw what he ate: yoghurt, orange juice and a chocolate bar or ice cream. He would go days eating just that. I remember a colleague visited him for a while and came back horrified; he said a week would go past where all they would eat would be nuts and figs – nuts and figs for lunch, nuts and figs for dinner. If they had dinner.”

The long separations took their toll and the marriage eventually petered out. Loro was brought up by Ana, and grew up hearing of his father’s exploits as leader of East Timor’s diplomatic wing. At first the boy idolised, then grew to resent his absent father, who would go most of a year without visiting. Ana herself says there was little choice: “We needed him at the United Nations and couldn’t send anyone just to be with him. In the end, he was condemned to loneliness in order to advance the cause.”

It was the rise to power of Xanana Gusmão as head of the Timorese resistance in 1981 that reinvigorated the movement. Like Ramos Horta, the new leader was a journalist, and later a poet and painter, who had joined Fretilin in the early days, a man full of youthful exuberance who was more often recalled for his basketball prowess than his prose. But in the jungles of tropical East Timor, following the death in combat of their military leaders, Gusmão was elected Falintil commander and grew into a formidable warrior.

At the time, not only the military leaders but all of the executive of the Fretilin government had been annihilated in combat or captured and killed. Falintil was broken into three rumps, with Gusmão in the furthest east of the country, in the mountainous terrain of Los Palos and unaware of the other two remnants.

He sent three separate undercover squads into the countryside to make contact with surviving units; only one made it through, and slowly, units were re-united. Gusmão then travelled the countryside, meeting clandestinely with ordinary people and asking, ‘Do you want us to continue fighting? Should we continue the struggle?’. Everywhere he went, he heard the same answer: ‘yes’.

Falintil was retrained and tactics were changed. Attacks were fewer, better planned and targeted the rear column of Indonesian convoys. Gusmão resigned from Fretilin, as did all of his soldiers, and made Falintil a non-political armed forces. He created an umbrella political body which he invited all parties to join, a body he headed and which eventually became the National Council of Timorese Resistance (CNRT).

Ramos Horta was appointed his special representative abroad, head of the diplomatic wing of the struggle and Gusmão’s deputy. Some guerrillas were demobilised and sent into the towns, to establish a clandestine front that could collect intelligence and work underground for the resistance. All of this began to pay off. Success occurred on the battlefield but also with the dramatic improvements in intelligence and coordination between armed units and the underground. And finally, thanks partly to better communications technologies like faxes, mobile phones and later satellite phones, the resistance command inside began to communicate and coordinate with their compatriots in exile, including Ramos Horta.

From his mountain hideout, Gusmão sent orders abroad and discussed tactics at the United Nations with Ramos Horta. It was during this period that Ramos Horta, after much correspondence with Xanana, devised a peace plan that would allow Indonesia a face-saving exit from the territory, with autonomy for East Timor over five to 12 years, ending in a U.N.-supervised referendum on integration with Indonesia or independence. The innovative and conciliatory plan was formally proposed in 1992 and, although immediately dismissed by Indonesia, it won plaudits in diplomatic circles and showed the Timorese were open to negotiating a resolution.

Then came the murder of Sebastião Gomes in October 1991. Although student activists like Gomes had been tortured and been ‘disappeared’ or killed during Indonesia’s long occupation, Gomes’ death was to set off a chain of events that eventually saw Indonesian troops leave in ignominy and disgrace almost exactly nine years later and end Ramos Horta’s long exile.

What has become known as the Dili massacre of November 12, 1991 had begun as a morning funeral procession in honour of Gomes, a clandestine operator who was killed by Indonesian troops while hiding out in Dili’s Motael Church. Outraged by the violation of the church’s sanctity and the death of a popular young man, hundreds marched from the church to his grave at Santa Cruz cemetery.

At the cemetery, young members of the clandestine front unfurled banners calling for independence and waved banned flags of the Falintil guerrilla army and Fretilin. In Australia, we would call this a peaceful demonstration. To Indonesian officers, this was open provocation, a display of the kind of resistance that Jakarta denied even existed.

And it was led by men and women in their teens and twenties, a generation that had grown up speaking Bahasa and saluting the Indonesian flag, and was not even alive when the Portuguese ruled in their benign and disinterested way. Indonesian troops opened fire on the crowd at the entrance of the cemetery. East Timor’s Catholic Bishop Carlos Belo, who attended the aftermath, estimates that at least 250 were killed.

Unlike other massacres in East Timor, this one was captured by the cameras. Three Western journalists – one British, two American – were in the crowd. The TV images, smuggled out and broadcast two months later galvanised the world’s attention on East Timor in a way no other event had before it.

“It catapulted East Timor to the international front page,” says Ramos Horta. It was an opportunity he did not miss, plying the airwaves and knocking on diplomatic doors around the world. It triggered an outpouring of guilt in Portugal, where the government was forced to push for a solution.

Incoming U.N. Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali appointed a special envoy to deal with East Timor, and himself brokered several meetings between Indonesia and Portugal trying to resolve the issue. Citizen’s support groups sprung up around the world, and activists began to make the job of Indonesian diplomats hell wherever they went. The U.S. Congress cut aid to Indonesia, as did many European governments. Suddenly, the world’s eighth largest country and one of the economic powerhouses of Asia, always courted by other nations, was finding it harder to keep friends.

Then came the Nobel Peace Prize in 1996. On October 12 that year, Ramos Horta was playing with his niece at his mother’s modest rented apartment above a pizza shop on the outskirts of western Sydney when he got the call.

“I just could not believe it,” he recalls. “We had been lobbying for Bishop Belo to get it for a few years, and to be frank I had completely forgotten about it.” Both he and Belo were awarded, the bishop for his interventions with the Indonesian military to save the lives of the tortured and detained and Ramos Horta for his peace plan of four years earlier.

The announcement shocked and dismayed the Indonesian elite. Belo they could tolerate, being a man of the cloth who eschewed discussion of Indonesia’s claim over the territory. But Ramos Horta had long been an enemy, repeatedly derided as a one-man band pushing an old cause no-one cared for.

An irate Indonesian Foreign Minister Ali Alatas called Ramos Horta “a political adventurist” and “a very clever manipulator” who incited the Timorese from a safe perch abroad. Newspaper editorials dubbed him an “opportunist of mixed blood” and “the Pied Piper” of a non-existent resistance.

“Are we going to surrender to the sight of foreigners trampling on us and making fools of us with this Nobel?” Indonesian armed forces spokesman Brigadier-General Amir Syarifuddin asked rhetorically.

It was only eight months later that economic ruin swept through Asia like a firestorm, hobbling Asian tiger economies and exposing the corruption and mismanagement that had been hidden by double-digit growth. None was hit worse than Indonesia.

Students and democracy activists took to the streets and by July 1998, the 32-year reign of General Suharto, the authoritarian leader and architect of the invasion of East Timor, had ended. Indonesia was facing economic ruin and Suharto’s replacement, former vice-president B.J. Habibie, caved in to international pressure and offered to resolve the issue of East Timor once and for all: with a U.N.-supervised referendum. On August 30, 1999, the Timorese came down from the mountains and the towns and voted 78.5% for independence.

By the time the U.N. plane touched down in Dili just before sunset, people had been waiting for hours. News of Ramos Horta’s return had spread by word of mouth through the shattered and burned out town, which like many throughout East Timor had suffered the consequences of rejecting Jakarta’s rule in a last orgy of violence by the departing Indonesian army and its militias.

Ramos Horta was greeted by a bevy of Timorese leaders who embraced him warmly, many of whom had fought the struggle on the ground and paid in blood. The four-kilometre ride from the airport to the city’s old colonial heart was impassable, so many had thronged the streets to greet the returning leader.

The U.N. Range Rover finally gave up on the outskirts of the city centre, so choked were the roads with well-wishers, and he stepped out to walk the last few kilometres to the old Governor’s Palace, from which the Indonesians had ruled and the Portuguese before them. Now, above the main entrance hung a simple blue banner with white lettering, reading “UN”.

A honour guard of old warriors wearing traditional garb, beating drums and blowing trumpets lead him to the entrance, where a podium was set up. Thousands of people packed into the Dom Henrique beachfront park that abuts the old Governor’s Palace.

There was wild cheering as Ramos Horta approached the microphone and, as the light began to fade, he shouted in a voice hoarse with emotion, “Viva the people of East Timor!”. The crowd erupted with, “Viva!”

“Viva Xanana Gusmão!”

“Viva!”

“Viva Falintil!”

“Viva!”

“Viva CNRT!”

“Viva!”

Speaking the local language of Tetum, he leaned into the microphone, his voice at times shrill. The crowd subsided to listen, but was soon clapping and cheering wildly again, ecstatically, with mouths open and eyes agape.

“I did not come today, after 24 years, with my colleagues to teach lessons to anyone, because the true heroes are those who stayed behind. They who have suffered, who were tortured, who were raped, they’re the ones who were killed. With humility, we bow to their courage, the courage of our brothers and sisters in this land.”

When he concluded, a chant started in the crowd that rippled through the thousands standing in the twilight and grew into a thunderous roar: “Viva! Viva! Viva! Viva! Viva! Viva! Viva! Viva!”

Twenty-four years of knocking on diplomatic doors and imploring for help at church gatherings, of arguing East Timor’s case at the United Nations and struggling to get the issue noticed in the media, of sleeping on friends’ sofas and borrowing money for airfares back and forth across the globe – all came to an end right here. In this wild and humid December night in the town where he was born, and to which he had promised to return within a few weeks of his departure.

A few days later, on the anniversary of the invasion that kept Ramos Horta from his homeland, he attended a service at Motael Church. It was within the whitewashed walls of this building, still standing, that the young Sebastião Gomes had been shot, triggering the series of events that culminated in the end of Indonesian rule and the painful transition to East Timor’s independence. It was another muggy day in Dili, but Ramos Horta was in good spirits.

“I feel extremely happy,” he said “But also I am conscious that all is not going to be rosy. We have to start from ground zero. We have to build political institutions, economic infrastructure, draft a constitution, create a legal system, provide health care, schools, food aid. But I am very optimistic. We have a great people and a lot of support from the rest of the world.”

He eschews any role in the government that will be formed after independence is granted by the United Nations Transitional Administration, which is now formally in charge of the territory.

He wants to settle down, teach aspiring Timorese diplomats and take up writing again, mourning that the best years of his writing life have passed him. “I want to stay here. I have been away for 24 years.”