By Timothy Pratt

A day or two after the mob violence at the Capitol, I noticed that CNN anchor Jake Tapper had said on air, four minutes before a 6 pm curfew entered into effect in Washington, D.C., “It's surreal, I feel like I'm talking to a correspondent reporting from...Bogotá.”

For nearly a decade, I was one of those correspondents – print and online, not TV. I had already been making the same associations in my mind.

While watching the videos and reading what we know about how the assault on the Capitol had been planned, I recalled the months before we left the Andean country. It was late 2000 and the chaos engulfing all of us in the city of Cali was asphyxiating. Most of the city’s two million caleños, caricatured in the rest of the country as beset with a desire to start the weekend early, in a city known as la capital de la salsa, couldn’t take another day’s headlines. Things had gotten so overwhelming that a petition began circulating to cancel the city’s end-of-year, week-long blowing-off-steam celebration called la feria.

It had been a terrorizing year. I reported for the Associated Press on a kidnapping of more than 100 men, women and children from a Sunday mass – one of the largest in history. Kidnapping had become a tool of terrorism used by guerrillas, paramilitaries, drug cartels and other armed groups mixed up in what was then the hemisphere’s longest-running civil conflict.

There was also the case of 7-year-old Dagoberto Ospina, who was taken, at gunpoint, off a school bus. I reported on that as well.

Newspapers and TV news broadcasts began making decisions like only showing photos of bombings or battles in black and white, or not covering kidnappings of journalists at all; these were sui generis bids by the media to stem the bloodshed.

At one point, I talked with my wife, Joana, about our daughter Jesse, who was not yet four, and who took a bus from our colonial, cobblestoned neighborhood to her nursery school every day. We decided to ask the school’s director if it would be a good idea to inform the police precincts along her bus route about me, a permanent resident in Colombia, but a U.S. citizen by birth. Maybe one of the armed groups would see Jesse as a prime target?

The answer we got was, “No, why would you do that? The police in those precincts are probably working with the kidnappers!”

Last Wednesday and in the following days, I flashed on that moment and many others I and millions of others lived through in Colombia in the last part of the last century.

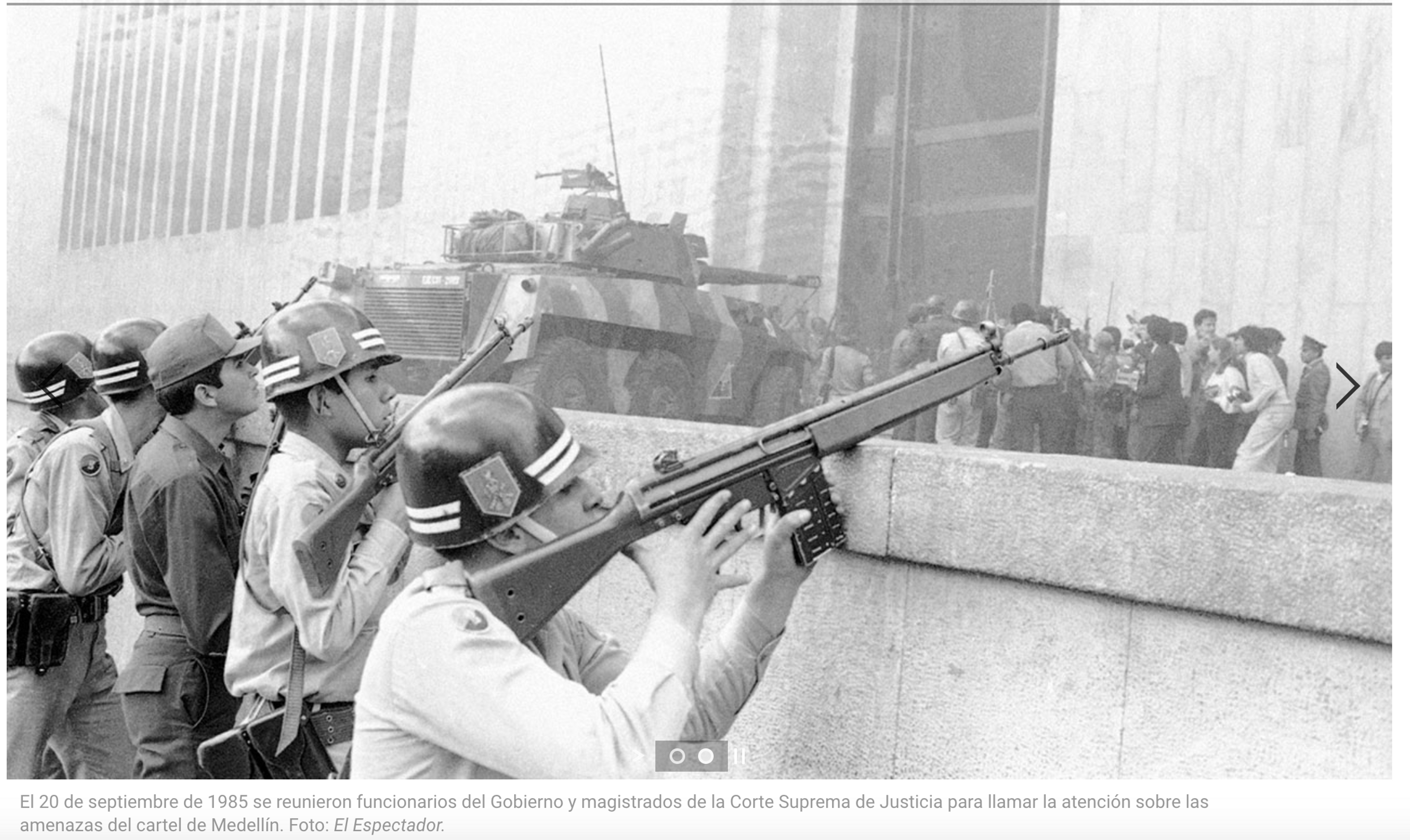

At one point last week when the cameras panned out and showed the Capitol under siege, an image came to mind from decades earlier: the 1985 storming of the Palacio de Justicia by 35 members of the M-19 guerrillas, who used the shocking assault to draw attention to the government’s broken promises regarding a ceasefire. Something in my mind linked the two: a center of justice in the capital city of Bogotá overtaken by violence nearly 36 years ago, and the halls of Congress overrun by armed mobs last Wednesday on live TV. Of course, in Bogotá, the results were more grim than in Washington, D.C., especially in terms of loss of life: the state responded by sending out 10 tanks and soldiers with grenades and missiles. A day later, nearly 100 people were dead, including Supreme Court justices, and 11 people had disappeared.

It was later revealed that someone had given an order to withdraw the police normally charged with protecting the Palacio de Justicia before those 28 hours of chaos in Bogotá. This despite the government having acquired intelligence that the guerrillas were planning such an assault. Decades later, details on who was involved from the inside, as well as others surrounding the casualties, remain hazy.

A Truth Commission has been working on clearing up that haze in recent years, after decades of government obstruction. Violence did not pause after the center of justice in Colombia became a field of battle that day in 1985, as seen in the years leading up to and including 2000, months before I left the country with my family, hoping to find safety and peace in the U.S.

A couple days ago, I mentioned my mental connection to those events to two different Colombian friends. “Yeah, the only thing missing was the tanks,” they both said.

Within days of the U.S. Capitol swarming with mobs seeking to hang or possibly kidnap members of Congress and the vice president, as the death toll from the attack reached five people, social media platforms tried to develop their own policies to stem the violence, including banning the president. Democratic members of Congress revealed that groups of unauthorized visitors were roaming Capitol halls the day before the violent mobs stormed the building. The FBI issued warnings about the plans of more armed mobs, this time at statehouses nationwide, in the days leading up to Joe Biden’s January 20th presidential inauguration.

On Sunday afternoon, our family took advantage of a slight reprieve from Georgia’s nippy January and we took a walk in a state park nearby. Circling a bend around a lake, we passed three older white folks. I heard the words, “second amendment.” My wife said in Spanish, “maybe they’re planning the next attack.” More gallows humor, nervous laughter.

So now we find ourselves with a police and military we can’t fully trust and a divided populace. Details of exactly how an armed, angry mob defiled the nation’s center of government, and who was behind it, remain undiscovered. Social media is attempting to take responsibility for its role in ramping up chaos. And many of us feel on edge, in anticipation of what’s to come.

The memories of millions who have come to the U.S. from other countries where capitols have also been targets of conflict from within have also likely been jarred this week. And at least two things are clear to anyone who’s lived through such a moment: first, discovering what happened, how, and who was involved, only comes to pass if there’s a sincere, sustained and public effort to do so, and second, these moments of violence are usually followed by others.