U.S. Tariff Overhaul Will high import taxes harm America’s economy?

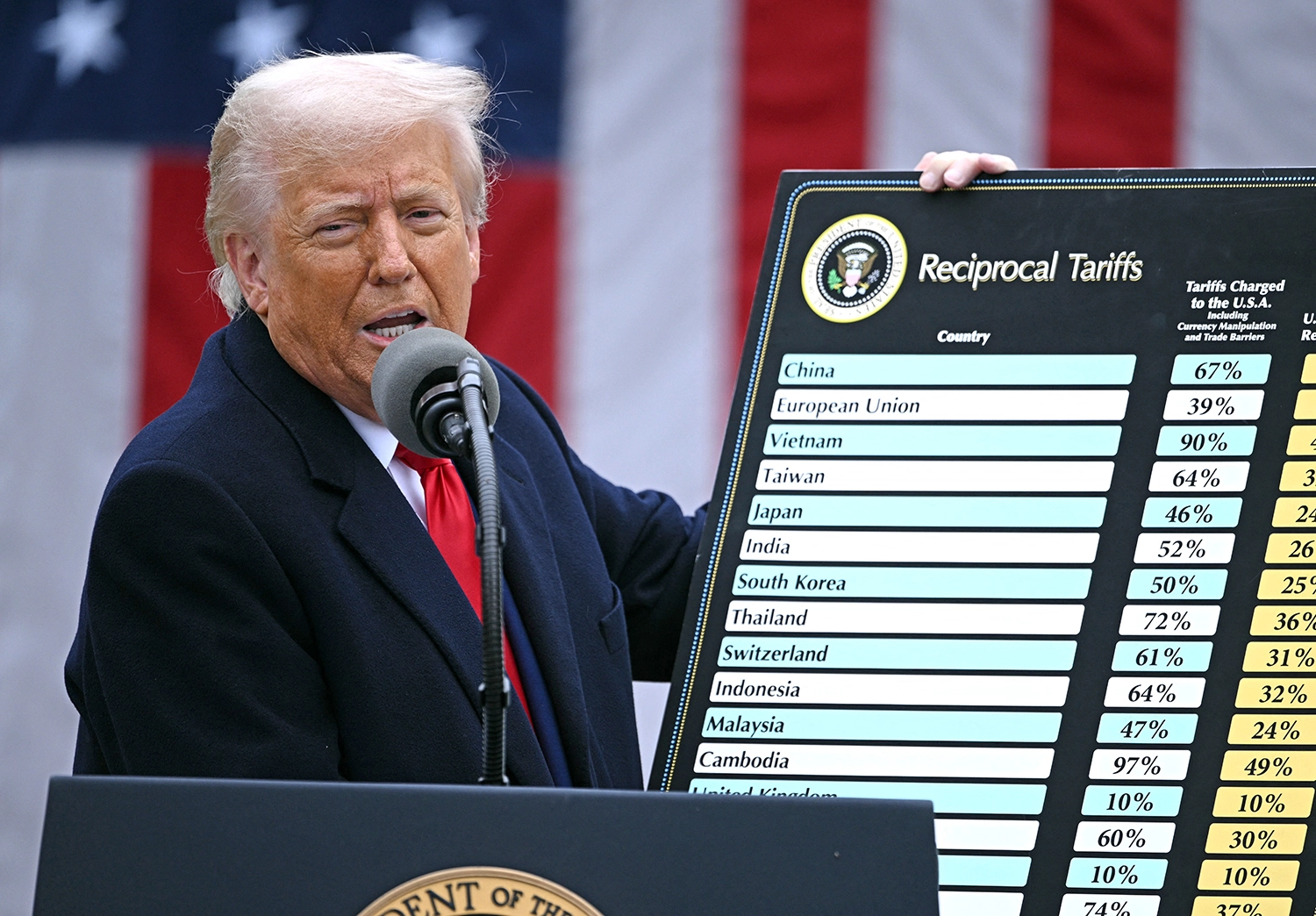

President Trump announces his “Liberation Day” plan to raise tariffs on imports on April 2 at the White House. (AFP/Getty Images/Brendan Smialowski)

President Trump’s trade strategy — using import tariffs and other punitive trade barriers as leverage to renegotiate with virtually every nation on Earth — promises to upend decades of free trade policies championed by the United States since the end of the Great Depression. His aggressive approach has alienated America’s allies and rivals alike, as he suspends, adds and threatens high tariff rates while negotiating with trading partners. It’s also flummoxed businesses worldwide and upended supply chains. His moves are hailed by some supporters who believe protectionist policies will return manufacturing to America, restoring well-paid jobs that don’t require a college diploma and have been lost to countries such as America’s biggest economic rival, China. Some firms have announced plans to build more plants in the United States, in part to avoid tariffs, but such projects can take years and cost billions. Most experts say the tactic is ill-advised and will raise consumer prices, slow growth and threaten America’s status as a global economic powerhouse.

Overview

To Learning Resources CEO Rick Woldenberg, President Trump’s sweeping on-again, off-again tariffs ― taxes paid by U.S. firms on imported goods ― aren’t just devastating for his educational toy business. They’re a body blow to the economy. “This path is catastrophic,” said Woldenberg, whose Vernon Hills, Ill.-based, educational toy business has about 500 employees. “Forces have been unleashed in the economy — the world economy as well as the U.S. economy — that will have consequences that will be irreparable.” 1

Kathy Ortiz, an employee of Learning Resources — an educational game and toy manufacturer in Illinois — gathers products to fulfill an order. Learning Resources and another toy company have asked the Supreme Court to fast track their court case against Trump’s tariffs. (Getty Images/The Washington Post/Contributor)

Nonetheless, he hopes they can be mitigated. In an effort to do so, Woldenberg sued Trump and administration officials in federal court — and won. The administration appealed, and the appeals court put Woldenberg’s victory on hold while another court considers a similar and broader case working its way through the appeals process. The current tariff rates remain in effect for now. So, on June 17, Learning Resources and another toy company, hand2mind, asked the Supreme Court to expedite a decision on Trump’s use of emergency powers to impose these tariffs. The Supreme Court declined an immediate ruling but is scheduled to decide on the request in July. On July 17, the Trump administration asked the Supreme Court to reject Learning Resources’ request. The justices “should not leapfrog those fast-moving” lower court proceedings in the case, U.S. Solicitor General D. John Sauer told the justices in a filing. 2

Though Learning Resources designs its toys in Illinois and in California, like about 80 percent of toys sold today in the United States, they are mostly made in China. At one point in April, after several escalations, Trump raised Chinese tariffs to 145 percent, 125 percent of them on overall imports and 20 percent tied to a dispute over fentanyl imports. At this (so far) peak rate, Woldenberg estimated his firm’s annual import duties might rise to about $100 million from $2.3 million, a more than 4,000 percent increase. But while that high rate was paused on May 14 to allow more time for negotiation and is currently at roughly 30 percent for most Chinese-made items, the ever-changing levels and White House announcements make it difficult to operate. “How am I supposed to make a business plan under these circumstances?” Woldenberg asked. “I don’t even know what my costs are going to be. I’m living in a reality-television show, not reality.” 3

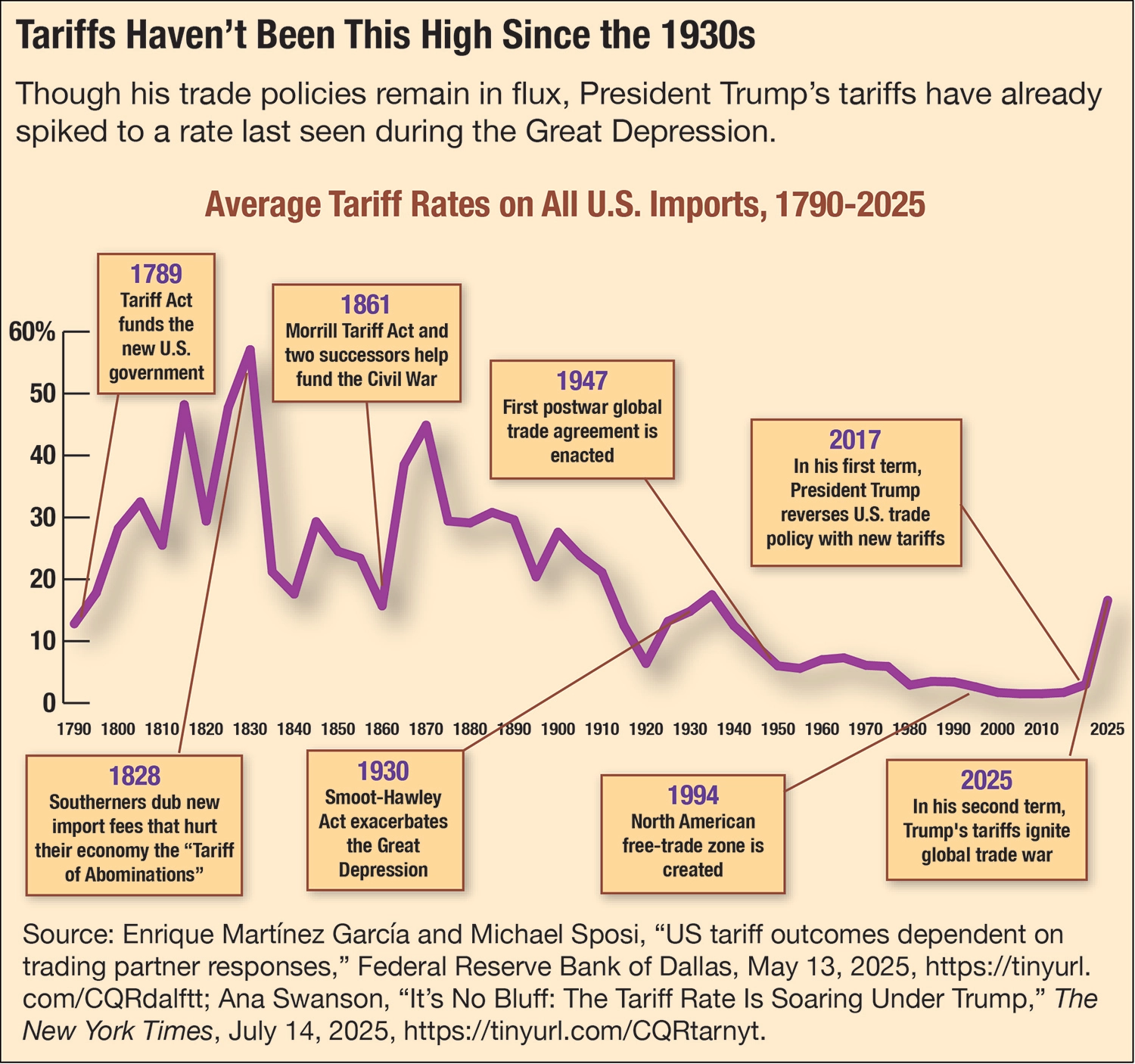

The toy companies contend the administration exceeded its legal authority when, on April 2, which Trump deemed “Liberation Day,” it imposed sweeping tariffs on imports from virtually every nation. Since taking office for the second time in January, Trump has rapidly employed tariffs ― raising, pausing and lowering them frequently ― as he negotiates with dozens of trading partners. He aims to use tariffs to raise funds for the federal government, expand domestic manufacturing, shield U.S. industries from foreign competitors and bend allies and foes alike to his will. To do so, he’s raised tariffs on imported goods to levels not seen in nearly a century. The policy and constant changes have upended supply chains (the network of suppliers who provide the components and materials that go into a finished product), enraged and eroded trust with allies such as Canada, the European Union (EU), Japan, Mexico and South Korea and injected uncertainty into the economic climate. Trump’s approach raises questions about whether tariffs will lure manufacturers back to the United States, spur Congress to take back control of tariffs from the executive branch and lead consumers to alter their spending. 4

Although the president has frequently claimed tariffs are paid by the country which they are levied against, tariffs are actually paid by the U.S. importers of goods made in those countries. From automakers to electronics manufacturers to retailers, companies bear the financial burden. They must either absorb the cost or pass it on to customers, or a combination thereof. 5

Tariffs typically serve three main purposes for the federal government:

- Creating overseas market access for U.S. firms by lowering foreign trade barriers, including tariffs through international agreements that may also lower tariff levels for imported U.S. goods. 6

In the April 2 announcement’s aftermath, stock markets lost more than $6 trillion in value over several days, delivering the worst performance since 1974 in the first 100 days of a presidency, because investors were concerned the tariffs would raise prices and send the economy into recession. Bond prices fell, and yields on U.S. treasury bonds rose (bond prices move in the opposite direction to their interest rates, or yields). The dollar’s value dropped compared with other currencies. 7

“Developments in the last 24 hours suggest we may be headed for serious financial crisis wholly induced by US government tariff policy,” Larry Summers, the former U.S. treasury secretary, Harvard University president emeritus and economist, said in an April 9 social media post. 8

A garment factory in Lesotho sits empty in July. Tariffs imposed on goods from the southern African country resulted in canceled orders, which forced the owner to close the facility and send workers home. (Getty Images/Per-Anders Pettersson)

On April 9, Trump announced 90-day pauses, dropping tariff rates to 10 percent for almost all countries except China, which initially retaliated and faced a cumulative tariff of 145 percent. On July 7, the White House extended the suspensions from July 9 to Aug. 1, except for China, which came to a separate 90-day suspension agreement with the United States on May 12. Under that agreement, most Chinese imports, as of July 8, retain a tariff rate of about 30 percent. That excludes “sector” tariffs, such as broad steel and aluminum imports. 9

By early May, stock markets had mostly recovered to pretariff announcement values. By July 3, the S&P 500 index reached an all-time high because investors were more optimistic that the White House would strike favorable deals as it paused or backed off more tariff threats. 10

“Normally, all this circus or noise around tariffs should bring uncertainty, should hit consumer sentiment, should hit inflation, maybe profit margins,” said Vincent Mortier, chief investment officer at Amundi, Europe’s largest asset manager. “At the end of the day, it’s fair to say that markets are just going to the next phase, anticipating that the impact won’t be that high and that finally the U.S. will probably win this game.” 11

On April 18, an open letter from hundreds of economists and other experts opposing the tariffs, particularly the April 2 across-the-board import taxes, began circulating. The signatories argue “the current administration’s tariffs are motivated by a mistaken understanding of the economic conditions faced by ordinary Americans.” By July 20, the number of signatories had reached 1,985. The group argues ordinary Americans will shoulder the burden of higher import taxes and that the tariffs will eventually cause a recession in the United States. 12

Justin Wolfers, an economist at the University of Michigan, said, “Perhaps there’s an argument to be had about the usefulness of tariffs. But I don’t see how anyone can defend incoherent tariffs. That incoherence makes the Trump tariffs immensely more disruptive than they need to be.” 13

Trump said he was able to impose across-the-board tariffs, even though the constitution grants tariff powers to Congress rather than the executive branch, by declaring a national emergency under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA). Trump is the first president to declare an IEEPA emergency to impose tariffs. Until now, the statute has been reserved for imposing sanctions in response to geopolitical situations, such as when a country takes political or military actions that violate human rights or international laws or norms. Those typically have involved seizing leaders’ property, as the United States did against Russia after it invaded Ukraine in 2014 and 2022, or as it did in 2008 against North Korea for its development of nuclear weapons. 14

The Court of International Trade, a federal court specializing in trade law, ruled on May 28 that Trump doesn’t have “unbounded authority” to enact broad tariffs under the statute. The administration appealed the decision, and a federal appeals court is expected to begin hearing arguments at the end of July.

In Trump’s view, the trade deficits between the United States and its trading partners constitute an emergency. A trade deficit occurs when a country’s imports surpass its exports, because it buys more from than it sells to its trading partners. 15

In 2024, the U.S. deficit for trade in goods with the rest of the world reached a record of nearly $1.2 trillion, according to U.S. Census figures. The United States has the world’s largest economy, even though it ranks a distant third in population, behind China and India. Thus, it is a major consumer of foreign-made goods, which are often cheaper than domestically made goods, in part because stronger U.S. worker and environmental protections drive up the cost of domestically manufactured goods. Mexico is the United States’ largest single trading partner, representing about 16 percent of total trade in goods, followed by Canada at 14 percent and China at 11 percent. U.S. imports dropped 16 percent in April compared with March, the largest monthly decline since 1992, which experts say was due to U.S. firms stockpiling goods in anticipation of tariffs. 16

Trump’s tariffs do not apply to services ― such as health care, education, financial and information technology and internet services ― which employ some 80 percent of Americans. In 2024, the U.S. services surplus, or when a country’s exports of services are greater than its imports, totaled $293.4 billion. 17

Trump called the April 2 tariffs “reciprocal,” a label most experts dispute. What is generally called a reciprocal tariff is when a country imposes a tariff on a trading partner and that partner levies a similar tax on American imports, usually in the same product category.

But Cullen S. Hendrix, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said Trump’s April 2 tariffs are not structured that way. Instead, they appear to be based on a simple formula derived from each country’s trade imbalance with the United States. The U.S. trade deficit in goods with a particular country is divided by the total imports from that country and then that number is divided by two. Then, an across-the-board 10 percent tariff is imposed on almost every nation. “Calling these tariffs reciprocal tariffs is like calling a cow a horse,” said Hendrix. 18

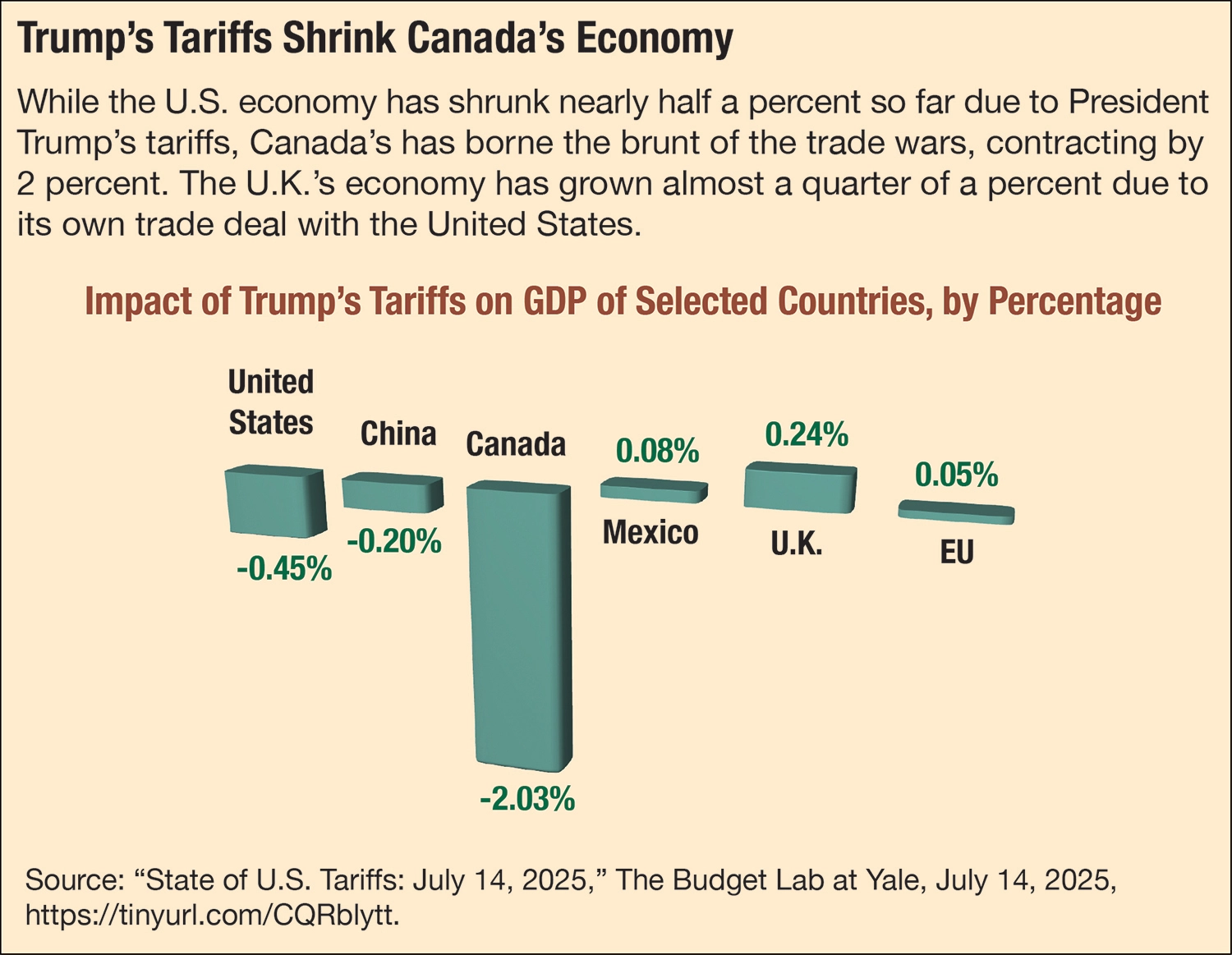

The Congressional Budget Office, which compiles budget projections for Congress, estimated on June 4 that if the tariffs remain in place, the resulting revenue would reduce the national deficit over the coming decade by some $2.8 trillion. The national deficit is the amount the country owes its creditors. But the levies may also shrink the economy and boost inflation by 0.4 percentage points this year. That will slash household purchasing power, the CBO said. Consumers will pay 0.9 percent more on an index of goods tracked by the office. In addition, retaliatory tariffs would amount to about half the value of tariffs imposed by the United States over the next two years, the CBO said, though it didn’t give an estimate and said it would include projections in its next report. 19

The ongoing trade war, accelerated by the tariffs, may mean consumers and companies will pay more for goods, which many predict will slow the economy. In April, economists surveyed by Bloomberg raised the likelihood of a recession to 45 percent, up from about 30 percent a month earlier. That’s a sharp turn from what a majority of economists categorized as the world’s strongest economy in the months leading up to Trump’s inauguration, after recovering from slowdowns tied to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. 20

For instance, the value of the U.S. dollar, used as a benchmark for many other currencies, and U.S. treasuries, typically seen as a safe-haven investment, suffered as some investors fled, driven in part by the tariff uncertainty. U.S. consumer confidence fell for the fifth straight month in April to a 13-year low before rebounding a little in May, as consumer anxiety over higher prices took hold, according to The Conference Board, a business think tank whose measurement of consumer mood is closely watched. Consumer spending accounts for almost 70 percent of the U.S. economy. 21

Meanwhile, a tariff-induced rise in inflation anticipated by economists is just starting to materialize, but it can take months for companies to decide whether higher costs — and prices — are permanent and for the expenses to work their way through the economic system. The Consumer Price Index, a government measure of inflation, rose 2.7 percent in June, the highest since February. Gregory Daco, the chief economist for EY-Parthenon, the strategy arm of tax firm Ernst & Young, estimated about one-third of the June CPI rise can be attributed to higher tariffs. These readings, experts say, have yet to fully reflect price increases working their way from cargo container to consumer. That’s because companies stockpiled goods ahead of the April 2 tariff announcement, said Omair Sharif, founder of the research firm Inflation Insights. 22

“It’s a matter of time before we really get everything pulling in the same direction,” Sharif said. Higher prices can take time to find their way to the consumer if companies absorb costs rather than pass them on. For example, in the early stages of the pandemic, rising costs from snarled supply chains and delays took a year to 18 months to work their way to consumer prices, according to an analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. 23

That explanation aligns with projections from the World Bank, The International Monetary Fund and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. All three global organizations that provide financial support, policy analysis and data with the goal of fostering economic stability worldwide forecast Trump’s trade policies will slow global economic growth in the coming year. 24

The World Bank in June forecast the slowest global economic growth of any nonrecession year since 2008, when a financial crisis began and then spread across the globe, leading into the Great Recession. “The global economy was stabilizing after an extraordinary string of calamities both natural and man-made over the past few years. That moment has passed,” Indermit Gill, chief economist at the World Bank, wrote in a report. 25

Trump says tariffs will spur large swaths of manufacturing that shifted overseas during the past half-century to return to the United States. U.S. manufacturing employment peaked in 1979 at 19.6 million jobs, about 22 percent of the workforce. Today, manufacturing employs almost 13 million people, or less than 10 percent of workers. 26

“Jobs and factories will come roaring back into our country,” Trump said on April 2. “And ultimately, more production at home will mean stronger competition and lower prices for consumers.” 27

The states that comprise the “Rust Belt” lost roughly 2 million jobs between 1998 and 2010 as firms sought lower-cost production abroad, notably in China. Rust Belt states generally include Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin. 28

The White House aims to “to fill up all of the half-empty factories that are now operating at low capacities around Detroit and the greater Midwest area,” said Peter Navarro, the White House senior adviser for trade and manufacturing. 29

But such moves can take years and cost billions, depending on a company’s goal and requirements. For example, a semiconductor plant can take three to five years to build, while an automobile factory can take up to two years, according to analysis from Wall Street firm Goldman Sachs. Samsung, which in 2022 announced plans to invest $17 billion in 11 new semiconductor plants in the United States, says the first one will open in 2026. However, innovations in software, 3-D printing and robotics may mean the numbers and kinds of jobs lost when firms moved abroad may not return. 30

In addition, tariffs can create jobs for one industry while destroying them in a related industry, some economists say. For example, tariffs on steel and aluminum ― designed to protect U.S. producers of those materials ― drive up costs for industries that use steel, such as manufacturers of automobiles, washing machines and electronics. Steel tariffs imposed in 2018 helped add 1,000 American steel industry jobs but resulted in some 75,000 fewer jobs being created in industries that use steel in their products, according to one study. 31

CEO Rick Huether of the Independent Can Company, in Belcamp, M.D., inspects a manufacturing line in June. Although the company makes its products in the United States, something Trump intends his tariffs to encourage, it is affected by steel tariffs because it imports materials. (AFP/Getty Images/Ryan Collerd)

“All of these tariffs are internally inconsistent with each other,” said Chad Bown, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, who maintains a tariff policy tracker for the Washington think tank. “So, what is the real priority? Because you can’t have all those things happen at once.” 32

Tariffs can be useful if they are “targeted” and part of a broader strategy, especially if the aim is to build up and move a new supply chain, says Susan Helper, an economics professor at Case Western University and adviser during the Biden and Obama administrations.

For instance, in September 2024, Biden levied a 100 percent tariff on Chinese-made electric vehicles, 25 percent on lithium-ion batteries and 50 percent on solar panels. Those came in addition to increased federal investments in manufacturing during his presidency, provided by the Inflation Reduction Act and the Chips and Science Act. 33

“We picked a few key sectors we thought were really important for national security, resilience, innovation reasons,” Helper says. “We said, ‘Let’s figure out what the barriers are to coming back.’ And a lot of those barriers are not just cost, but coordination and information.” Before investing in solar generation, the Biden administration needed to be sure suppliers were willing to build plants for parts such as wafers and ingots, Helper says. It is a “knife-edge thing. Neither investment is profitable without the other. Bring them together, make sure that they’re both going to do it. Help people understand the options and the opportunities.” In addition, the pay, benefits and job security must improve to attract workers, Shawn Fain, president of the United Autoworkers Union, said in an April speech about how tariffs and other policy positions could impact manufacturing workers.

Fain said free trade had been “a disaster for the working class,” decimating some communities, as jobs migrated to places with lower wages and there was inadequate re-training for new industries. American auto companies can afford to bring back workers, Fain said, and “strategic tariffs can play a role in that,” along with good worker protections. “We don’t support the use of tariffs for political gains about immigration or fentanyl; we do not support reckless chaotic tariffs on all countries at crazy rates,” Fain said. “We support and have always supported tariffs on the auto industry, on heavy trucks and on agricultural implements. The difference is, the auto tariffs are designed for a specific purpose. They raise the [import] costs of the companies that have killed good jobs in a race to the bottom for cheap labor elsewhere, while Wall Street makes a killing.” 34

In May, Ford said Trump’s tariffs would cost it about $1.5 billion, while General Motors estimated they would cost it between $4 billion and $5 billion. GM said in June it is investing $4 billion in U.S. factories over the next two years to help sidestep tariffs. Such tariffs,it added in July, cost the company $1.1 billion from April to June and are projected to cost even more in the next three months. 35

Trump said on the campaign trail it will take time for the United States to curb dependence on imports and rebuild manufacturing. Yet economists and corporate executives say the on-again, off-again tariffs make it difficult to plan ahead, stifling speedy — or, in some cases, any — investment in U.S. manufacturing. 36

U.S. manufacturing payrolls overall fell by 8,000 in May, the largest monthly drop this year. In the Rust Belt states, where more than 100,000 jobs have been added since 2021, some firms are delaying expansion plans until the tariff levels stabilize.

“The current operating mode is just the death to long-term investment,” said Andrew Anagnost, chief executive officer of Autodesk Inc., a seller of software used to design factories and speed processes. 37

Congress could slow down tariff-decision volatility by reasserting its authority and reining in some tariff powers, something the sharply divided Congress has failed to do. On April 2, the Senate voted 51-49 on a resolution to rescind tariffs Trump levied on Canada via executive order in early February, thereby ending 25 percent tariffs on all imports from Canada and 10 percent on energy products. The House has not yet voted on the bill. Canada has been one of the top two U.S. trading partners, accounting for more than $762 billion in trade in 2024, according to the U.S. Trade Representative, an agency that administers trade rules. All Senate Democrats supported the measure, as did four Republicans: Rand Paul and Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska.

However, the resolution is unlikely to get a vote in the House of Representatives, because the House passed a procedural measure in March tabling any vote addressing Trump’s tariffs until 2026. 38

On April 30, another Senate bill to rescind the April 2 tariffs failed, 49-49. The measure was co-sponsored by Sen. Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat, and Paul, who said Congress “lacks the fortitude to stand up for its prerogatives.” Noting that the Constitution forbids taxation without the legislative body’s approval, Paul added, “Congress didn’t debate these tariffs. Congress didn’t vote to enact these tariffs. The tariffs are simply imposed by Presidential fiat, by proclamation. Government by one person who assumes all power by asserting a so-called emergency is the antithesis of constitutional government.” 39

McConnell and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, a Rhode Island Democrat, were absent from the vote.

Sen. Mike Crapo, an Idaho Republican who chairs the committee overseeing trade policy, said legislators should be working with Trump. “I appreciate that many of us in this chamber have heard from constituents concerned about the economic impact of the tariffs,” Crapo said after the vote. “All of us are watching this issue closely and working with the administration to find ways to minimize its impact on Americans. We should also be working with the administration to address a shared objective: more opportunities for Americans in foreign markets and an end to discriminatory actions in foreign markets.” 40

A third bill, called the Trade Review Act of 2025, would require presidents to notify Congress of all new tariffs within 48 hours of declaration and provide an analysis showing their effects on businesses and consumers. Congress would have 60 days to review and approve the tariffs, after which they would expire if not approved. The bill was co-sponsored by Sen. Maria Cantwell, a Democrat from Washington state, and Sen. Chuck Grassley, a Republican from Iowa, generally seen as a Trump ally. It was referred to the Senate Finance Committee, where both senators serve. So far, it has seven Republican and six Democratic co-sponsors. 41

Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., speaks at a news conference about Trump’s tariffs in Washington, D.C., in April. Kaine coauthored a resolution with Republican Senator Rand Paul, which would have blocked tariffs on Canadian goods; while the Senate passed the measure, the House of Representatives decided not to vote on it or any similar bill until 2026. (AP Photo/Rod Lamkey, Jr.)

The measure is modeled after the War Powers Act, which mandates a similar notification of Congress before a declaration of war, Cantwell said. The act took effect in 1973 in reaction to President Richard Nixon’s expansion of the Vietnam War. “Congress, in the War Powers Act, decided to reclaim its authority because they thought a President had overreached,” Cantwell said. “Senator Grassley and I are trying to do the same thing today by introducing the Trade Review Act of 2025.” 42

Rep. Don Bacon, a Republican from Nebraska, introduced a similar version in the House. “This is less about the actual tariffs laid by the Trump administration, some of which I support because they are reciprocal, but more a commitment to uphold the Constitution,” Bacon said. “Congress has the power of the purse. Our Founders created checks and balances for a reason.” 43

House Speaker Mike Johnson said on April 30 that Congress could intervene, but he’d discuss it with the president first. “I think the executive has a broad array of authority that’s been recognized over the years,” he said. “If it gets close to where the imbalance is there, then we would step in.” 44

While choking off the president’s authority to impose tariffs is unlikely in today’s political climate, Congress can do other things to steer the White House into implementing them in more specific ways, says Kathleen Claussen, a Georgetown law professor and trade law expert who worked in the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative during the Obama and first Trump administrations. For instance, Congress could authorize Trump to take specific actions, such as promoting trade or negotiating certain deals, while narrowing the sweeping powers the White House says it has under the IEEPA.

“If they … gave him big trade promotion authority or even smaller trade negotiating authority, where they say, ‘We want you to do these deals, and here’s the process we want you to use to do them.’ That allows him to do what he’s already doing to complete his agenda to some degree,” Claussen says. Such action, though, would likely “create new sidebars that would say, ‘When you do this, we want to see the draft before this goes into effect, we want to pass a bill.’ So, it would at least again bring Congress into the conversation in a way that it’s not currently. But whether that’s in the cards — your guess is as good as mine,” Claussen says.

Since April, Congress has been mostly quiet on the legislative front, as Republicans say they want to give Trump’s approach a chance. “Republicans are trying to give the administration … some space to figure out if they can get some good deals and awaiting the results of that,” Senate Majority Leader John Thune said ahead of the April 30 Senate vote. 45

Will Trump’s tariffs change consumer buying patterns?

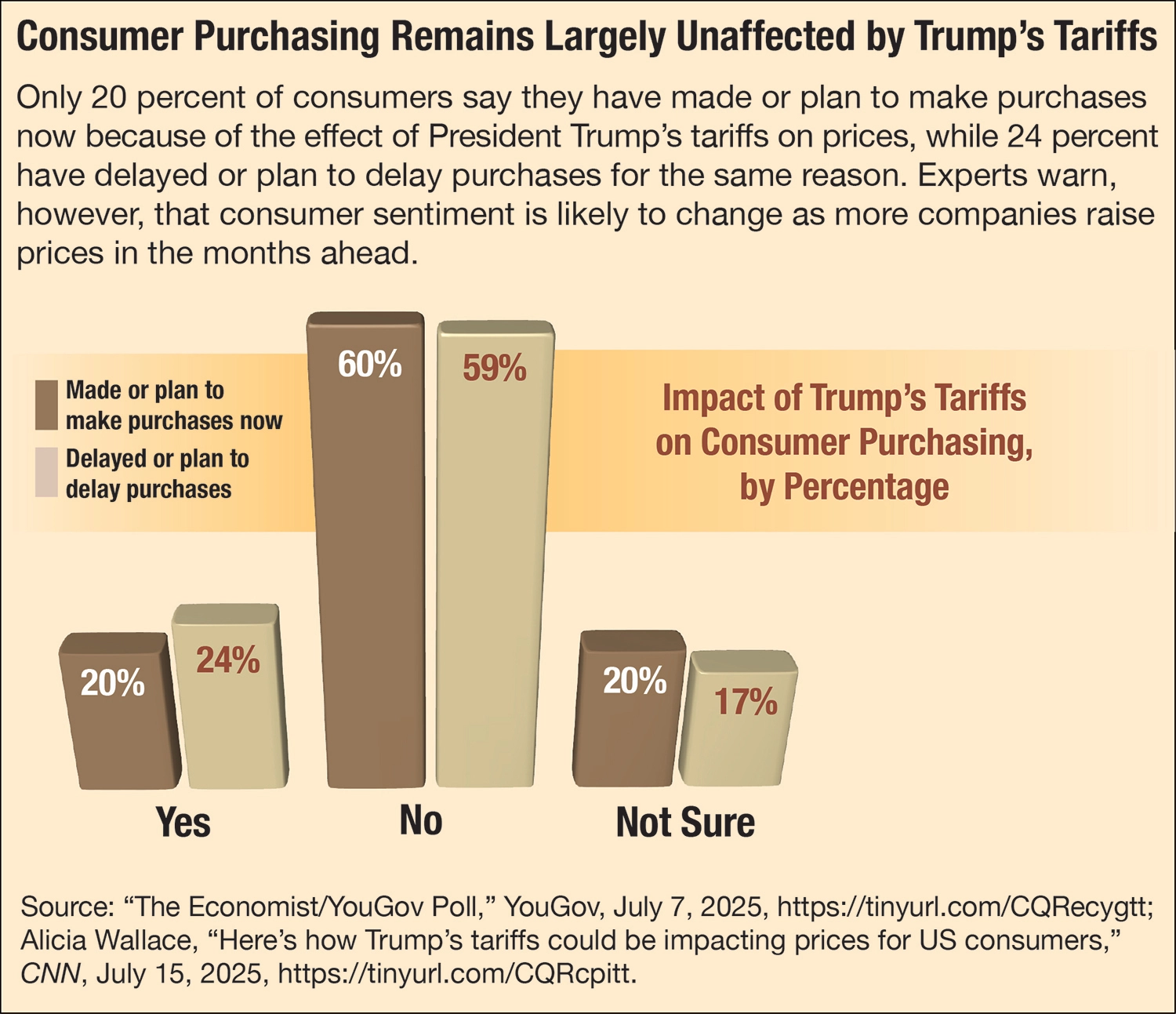

American consumers, whose spending accounts for almost 70 percent of the U.S. economy, may already be changing their purchasing patterns amid uncertainty about when tariffs may drive prices higher, according to a survey of 2,500 consumers released in May by audit firm KPMG.

More than two-thirds of respondents said they didn’t want to take on any more credit. About 43 percent said they were delaying an automobile purchase because of the tariff announcement, while 17 percent said they are accelerating plans to buy ahead of higher prices. People have cut back on smaller purchases, too: Most said they decided to watch streaming services with advertising rather than pay for commercial-free viewing. That seems to be a faster adjustment to potentially higher prices than what happened after the March 2020 onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Matt Kramer, who leads the consumer and retail business for KPMG in the United States. “They’re clearly looking at opportunities to save,” Kramer said. “They’re switching providers where it makes sense, whether that’s their streaming services, whether it’s looking at insurance providers.” 46

Consumers — and retailers — are worried the tariffs may blunt back-to-school and holiday shopping later this year, a possibility Trump himself acknowledged to reporters on April 30. “Somebody said, ‘Oh, the shelves are gonna be open,’” Trump said. “Well, maybe the children will have two dolls instead of 30 dolls, and maybe the two dolls will cost a couple of bucks more.” 47

Retail sales fell more than some analysts expected in May, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Retail and restaurant sales fell 0.9 percent, driven by a big drop in auto sales, after Americans rushed to dealerships in March to buy ahead of anticipated tariffs. When autos are excluded, retail sales dropped 0.3 percent. 48

That indicates consumers are starting to pay more — and are getting worried, economists said. The figures are “not a terribly encouraging report card in terms of how spending is holding up amid tariffs,” Wells Fargo economists said, adding that the data show “some signs of caution.” 49

Still, when major purchases are excluded, a measure called core retail sales, spending continues to rise at about the same pace as last year. That may be because of higher wages and a rebound in the stock market after the White House paused tariffs, said Jack Kleinhenz, a senior economic advisor for the National Retail Federation, which represents retailers. “Consumers are seeing their way through the uncertainty with trade policies,” Kleinhenz said, “but I expect the inflation associated with tariffs to be felt later this year. Consumers remain very price sensitive, and those costs are likely to weigh heavily on consumer budgets.” 50

Typically, retailers begin building stock for the holiday season in May and get seasonal items on the shelves in October. This year, orders surged early. “Companies pulled in freight to get out of the tariff crosshairs in March, April and May,” said Dean Croke, principal analyst at DAT Freight & Analytics, a freight tracking software and services firm. “Warehouse distribution surged at that time. We are essentially in peak season now.” 51

Still, the White House maintains that those seeking to export to the United States will absorb tariff costs, even though technically American importers pay the import taxes. “The Administration has consistently maintained that the cost of tariffs will be borne by foreign exporters who rely on access to the American economy, the world’s biggest and best consumer market,” White House Deputy Press Secretary Kush Desai said. 52

“Foreign exporters have ended up absorbing a lot of [the higher costs], and businesses — very little has gotten to consumers at this point,” said Mark DiPlacido, policy advisor at American Compass, a conservative economic think tank. He pointed to price cuts by Japanese automakers as an example. 53

Many such exporters are in China, which makes almost 80 percent of toys and more than 78 percent of laptop, tablet and smartphone imports sold in the United States. Some 97 percent of clothing and footwear sold in the United States is manufactured outside the country, including about a quarter in China, according to industry associations. But such groups do not expect exporters to absorb the increases indefinitely. 54

“With all back-to-school styles now facing tariffs of between 10-30 percent, higher prices should not be a surprise this summer,” said Stephen Lamar, CEO of the American Apparel and Footwear Association, an industry group. “While each company makes their own decisions, these tariff costs are now being felt across the board.” 55

In the United States, companies are already raising some prices because of tariffs, according to the Federal Reserve’s May Beige Book, which tracks business and economic conditions. They are either raising prices on everything or just on products impacted by tariffs and are cutting costs or adding temporary fees and surcharges. Firms that plan to boost prices to cover the tariffs plan to do so within three months, the Federal Reserve report said. 56

Makers of everything from Barbie dolls to Air Jordans to Ford F-150 trucks said in April and May they plan to raise prices in whole or in part to absorb higher tariff costs. 57

Through the spring and early summer, there was a “rapid but still relatively modest” increase in prices, according to Alberto Cavallo, a Harvard Business School professor who leads the Digital Data Design Institute at the Harvard Pricing Lab. “Our analysis reveals rapid pricing responses, though their magnitude remains modest relative to the announced tariff rates and varies by country of origin,” Cavallo said. 58

In response to rising prices, “the consumer is still being very conscious and very choiceful about what they’re purchasing, but it’s been consistent,” said Todd Sears, chief financial officer of Sam’s Club. 59

Automobiles are parked at the Port of Baltimore import lot in May. Manufacturers stockpiled inventory ahead of tariffs on imported cars and car parts taking effect. (Getty Images/Win McNamee)

Meanwhile, the volume of cargo entering America’s ports is also slowing, said Gene Seroka, the executive director of the Port of Los Angeles, the nation’s biggest. Cargo moving through the port in May, typically the strongest month, was the lowest in more than two years, falling 19 percent from April. “Unless long-term, comprehensive trade agreements are reached soon, we’ll likely see higher prices and less selection during the year-end holiday season,” Seroka said. “The uncertainty created by fast-changing tariff policies has caused hardships for consumers, businesses and labor.” 60

It won’t be clear how much prices are rising and what impact that will have on the economy overall until companies run out of merchandise stockpiled before the tariffs took effect, said Bob Schwartz, a senior economist at Oxford Economics. “That’s when we will get a better sense of whether tariffs have more of an impact on destroying demand or boosting inflation.” 61

Big retailers such as Walmart and Best Buy have already said they plan to pass on some tariff costs by raising prices. The higher tariffs began cutting into profit in April and increased in May, Walmart CEO C. Douglas McMillon told investors. 62

“The merchandise that we import comes from all over the world, from dozens of countries. Other than the United States, the other large markets are China, Mexico, Vietnam, India and Canada,” McMillon said. “China, in particular, represents a lot of volume in certain categories like electronics and toys. All of the tariffs create cost pressure for us, but the larger tariffs on China have the biggest impact.” 63

Walmart’s warning raised Trump’s ire, who told Walmart in a social media post it should “EAT THE TARIFFS.” He added “I’ll be watching, and so will your customers!!!” 64

Companies including Amazon, Adidas, AutoZone, Best Buy, ConAgra, Columbia Sportswear, Ford, GM, Nike, Stanley Black & Decker, Subaru and Target all signaled they will or may increase prices on at least some merchandise, including groceries. Home Depot in May said it won’t raise prices, but some products might not be available. 65

Still, in May, most companies appeared to be absorbing tariff costs, keeping prices lower than expected. “While it’s still too early to draw definitive conclusions, tariff collections are running at three times the monthly pace in May 2025 relative to May 2024, and the lack of meaningful pass-through to broad consumer prices suggests that businesses are (at least for now) absorbing a decent amount of the extra costs from tariffs,” said Carter Griffin, a global investment strategist with J.P. Morgan, a Wall Street investment bank. 66

Some anecdotal evidence suggests consumers, manufacturers and retailers are looking to avoid higher prices by buying from American companies. For The Rodon Group, a family-run injection molding company in Hatfield, Pa., business jumped after the tariffs were announced. The maker of K’nex toy sets, window parts and caps for beverage bottles began investing in automation in the 1980s and has been upgrading technology at its U.S. plants ever since. “Our phone’s ringing off the hook, email’s up, everything, because people are in panic mode,” said CEO Michael Araten, whose family founded the business in 1956. “It reminds me very much of the pandemic, where it’s a supply shock.” 67

Even with the pauses, consumers are facing an effective tariff rate of almost 16 percent — the highest in almost 90 years, according to the Yale Budget Lab. The average U.S. household is forecast to have roughly $2,500 less in spending power in 2025 than in 2024. When people have less purchasing power, they spend less money, and the economy slows. 68

Another complication: On May 3, the White House ended a loophole that exempted from tariffs any purchases of goods from China worth less than $800.

Large Chinese retailers such as Shein and Temu, which have surged in popularity in recent years, took advantage of the exemption by sending packages directly to U.S. consumers. The two firms comprise almost half of all such shipments from China, according to a 2023 Congressional report. 69

Closing the loophole will have widespread effects, not only on imported finished goods but also on small businesses that use Chinese-made supplies to make their products, economists expect. Sellers that use websites such as Amazon, eBay or Etsy to sell their products say they are in a bind. 70

elly Kendall, a Chicago-based small business owner who makes craft supplies and kits that sell for $30 to $100 on Etsy, said she relied on the exemption for about 80 percent of her materials. Finding a U.S. supplier is hard, because few offer what she needs. And even when she did find one, they wouldn’t sell to her because her order was too small. That, ultimately, may mean higher prices for her customers ― and fewer sales for her business. “I don’t think people understand the larger impact for really small businesses, where this is my main source of income,” Kendall said. “This is a big deal.” 71

Tariffs were the biggest source of revenue for the newly formed United States until the Civil War. The Tariff Act of 1789, one of the country’s first pieces of legislation, designated such import taxes as being implemented under federal, rather than state, authority. Customs houses collected duties for the U.S. Treasury. Most imports were levied at about 5 percent. 72

Two years later, Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury secretary, advocated for tariffs and bounties (government subsidies) to bolster manufacturing and economic development. Congress approved most tariffs but shunned the bounties. 73

After the War of 1812 with Great Britain, tariffs spurred a deep political crisis. A set of tariffs passed by Congress in 1828, later known as the “Tariff of Abominations,” imposed duties up to almost 50 percent on some manufactured imports and was championed by Northern states to bolster domestic manufacturing. Southern states’ agricultural and plantation-driven economies suffered in part because they imported many manufactured goods for machinery. In 1832, South Carolina, citing states’ rights, declared some of the tariffs unconstitutional and nullified them within its borders.

That December, President Andrew Jackson issued a proclamation declaring such action incompatible with national unity. Sen. Henry Clay of Kentucky, fearing civil war, helped craft the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which gradually lowered tariffs over a decade. The companion Force Act authorized military use to enforce the tariff. After Congress passed the law, South Carolina repealed its nullification. Clay’s dealmaking “helped save the union,” said Douglas Irwin, a Dartmouth College trade historian. 74

In the years before the Civil War, tariff revenues fell as Congress tried to open trade with other nations by lowering the levies. The federal government borrowed more to make up the shortfall. When war broke out in 1861, Southern states kept tariff revenue for themselves. Congress again raised tariffs that year, but the resulting revenue wasn’t enough to finance the war.

So, in July 1862, Congress approved the first U.S. income tax and other excise taxes and created the Office of Internal Revenue. However, after the war, tariff income was used to service war loans. In 1872, Congress voted to repeal the unpopular income tax. 75

In 1877, William F. McKinley, a Republican from Ohio, won election to the House of Representatives. McKinley — whom Trump said he admires — authored a bill that raised tariffs to their highest. McKinley’s tariffs became law in 1890. However, he tempered his stance on tariffs after he was elected president in 1896, calling for “a policy of good will and friendly trade relations.” 76

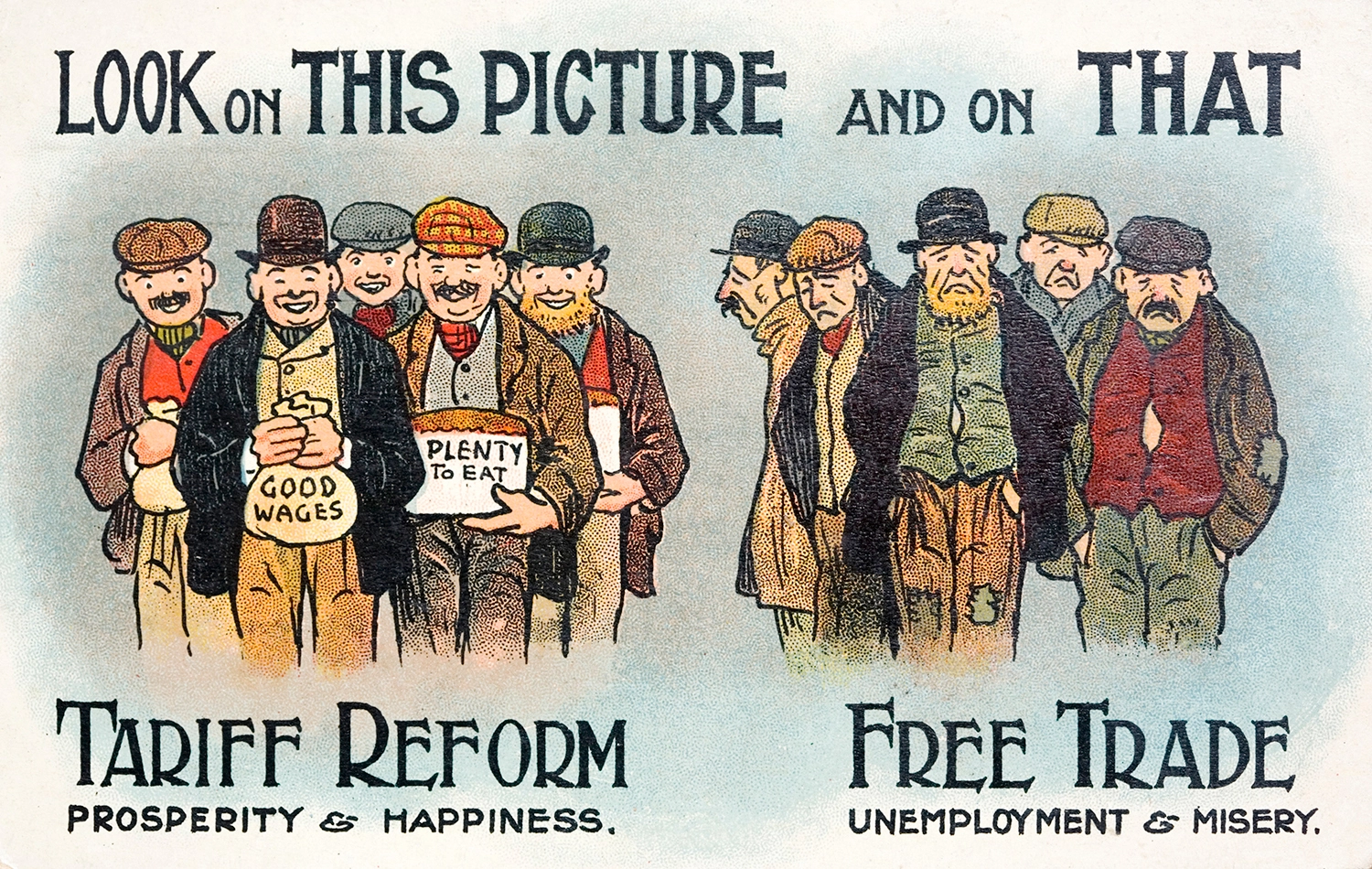

An illustrated card from 1910 depicts how tariffs have long been portrayed as an answer to plentiful jobs, wages and goods. (Getty Images/Corbis Historical/Michael Nicholson)

By 1913, Congress had ratified a Constitutional amendment codifying the income tax and enshrining the ability of the federal government to raise funds through that mechanism. President Woodrow Wilson pushed through the Underwood-Simmons Act, which included a limited income tax and lower tariffs. 77

After World War I, Congress raised tariffs to protect American farmers, as agriculture recovered in Europe and industries shrank after wartime production ended. But the levies, enacted in 1921 and 1922, were shrinking as a percentage of federal revenue, as income taxes became the largest source of funds. Tariffs were used mainly as political tools to encourage reciprocal agricultural and industrial policies with other countries. One of the levies enacted under The Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act of 1922 raised tariffs and authorized the president to raise or lower any tariff rate by 50 percent. In 1929, the stock market crashed, and the Great Depression followed. Some 9,000 banks failed. 78

When Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a measure of economic health, falls two quarters in a row, economists consider it a recession. A depression is measured by GDP declines of 10 percent or more for three or more years. So far, the Great Depression was the only depression in U.S. history. 79

As the economy started to sink, Rep. Willis Hawley and Sen. Reed Smoot, from Oregon and Utah respectively, responded by authoring a law to raise some tariffs by 60 percent. Congress passed it, ignoring the warnings of more than 1,000 economists, who signaled it would further damage an already struggling economy. President Herbert Hoover signed it into law in June 1930, the last time Congress directly set specific tariff rates on individual items. U.S. import volume dropped 20 percent in two years. 80

Smoot-Hawley’s passage into law, as the letter-writing economists had warned, led to a surge in retaliatory tariffs from trading partners and a sharp decline in international trade, exacerbating severe economic conditions, something most presidents since have used as a cautionary tale. “The Smoot-Hawley tariff ignited an international trade war and helped sink our country into the Great Depression,” President Ronald Reagan said in 1986. 81

Many economists say the Smoot-Hawley tariffs helped lengthen the Depression, but others argue that they weren’t as big a contributor to the Great Depression as some think and as popular culture portrays. “[T]he tariffs or the thought of having tariffs were not a cause of the Great Depression,” said Gary Richardson, economics professor at the University of California, Irvine, and former historian of the Federal Reserve System. 82

While not a direct cause, Smoot-Hawley helped escalate a global trade war and deepen the Great Depression worldwide, helping to create some of the conditions that led to destabilized economies in Europe and Asia, fueling the rise of dictatorial government regimes and further splintering pre-World War I alliances in the period leading up to World War II, according to the U.S. Office of The Historian. 83 Shortly after taking office in 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, signed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act as part of his New Deal package of legislation to revive the economy. The measure, which expired after three years, authorized the president to change U.S. tariff rates up to 50 percent from existing levels without Congressional action. It also authorized him to negotiate bilateral and reciprocal trade agreements. 84

After Roosevelt’s death in 1945, his vice president, Harry S. Truman, continued to pursue Roosevelt’s policies, including the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), a pact designed to promote peaceful trade, signed in 1947 by the United States and 22 other countries. 85

“There was clear acknowledgement that something had gone wrong in the 1920s and 30s, and we needed a brand-new approach,” said Chad Bown, a senior fellow at the Peterson International Institute of Economics (PIIE). 86

One major tenet of the agreement, which took effect on Jan. 1, 1948, mandated that all signatory countries be given most-favored-nation status, meaning all nations in the agreement would be treated equally. Between 1947 and 1993, eight rounds of GATT negotiations were held. In 1995, GATT was absorbed into the World Trade Organization (WTO). 87

For roughly 70 years after the creation of GATT, the United States pursued free trade policies, including lowering most tariff barriers. But tariffs didn’t go away. The White House shifted their purpose. The Trade Expansion Act of 1962, signed by Democratic President John F. Kennedy, authorized the president to lower or “impose restrictions on goods imports or enter into negotiations with trading partners” if the Commerce Secretary determines those imports “threaten to impair” national security. The law also authorized the president to negotiate tariff cuts of up to 50 percent. 88

The Kennedy administration developed the Trade Expansion Act partly in response to the formation of the European Economic Community (EEC). Created in 1957 by the Treaty of Rome, a group that eventually included 13 Western European nations, the treaty aimed to lower trade barriers, build up the region’s postwar economic strength and lower political tensions. The law contains a provision, Section 232, that allows the White House to impose restrictions on and enter into negotiations with trading partners if an investigation determines their exports threaten national security. In both terms, Trump used Section 232 to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum. 89

In August 1971, President Nixon declared a national emergency and imposed a 10 percent tariff on all imported goods. The measure, he said, aimed to rectify “unfair exchange rates” against the dollar and boost American jobs by leveling the playing field for American products. It was removed in December that year after the Group of Ten (G-10) reached an agreement to devalue the dollar relative to gold. The G-10, which actually consists of 11 countries, includes Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. 90

The Trade Act of 1974 allowed the president to negotiate tariffs and nontariff barriers and authorized the United States to fully join in the Tokyo Round of GATT negotiations, then underway. Under the law, the White House can cut import tariffs by up to 60 percent and eliminate those less than 5 percent. 91

Section 301 of the act, used by every president since, authorizes the U.S. Trade Representative to investigate and negotiate during trade disputes and take retaliatory actions such as tariffs if necessary. Another provision allows the president to take temporary action if imports are determined to be hurting domestic industry. 92

The Tokyo Round yielded new tariff rules when it ended in 1979. One major change required that countries investigate and report whether domestic industries are being harmed before a country imposes countervailing duties (import tariffs imposed in response to tariffs on a country’s exports). 93

In 1983, Republican President Ronald Reagan imposed tariffs on imports of Harley-Davidson motorcycles, made in Thailand and Brazil. In 1987, he implemented a 100 percent tariff on Japanese electronics, including semiconductors, televisions and power tools. The United States said Japan was selling semiconductors below market prices and blocking American chips from entering its market. Chip imports from Japan had almost doubled every year between 1981 and 1984 before waning during an industry downturn in 1985, undermining sales of U.S.-made semiconductors. In response to the tariffs, U.S. semiconductor jobs rose, but did not return to their higher levels. Some critics argued the measures ultimately hurt consumers. 94

In 1987, as one of its last acts, the Reagan administration negotiated a free trade agreement between the United States and Canada. Despite the targeted Japanese tariffs, the United States continued to expand its use of free trade agreements, building on post-World War II policies.

Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, decided to expand the agreement to include Mexico, negotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the first time two developed nations entered into a free trade agreement with a developing one. It eliminated or created a phase-out schedule for almost all tariffs between the three countries. Bush’s successor, Democratic President Bill Clinton, signed the measure in 1993 because Congress didn’t ratify it until then. 95

While North America was creating the biggest free trade bloc to date, the rest of the world was also expanding free trade rules. In 1994, during the Uruguay Round of negotiations, participating nations agreed to replace GATT with the World Trade Organization (WTO), which created a process for settling trade disputes, including tariffs, and aimed to reduce trade barriers. Today, the WTO’s 166 member countries account for 98 percent of world trade. 96

Meanwhile, China’s trading status with the United States required annual review to retain its most-favored-nation trading status. In the late 1990s, China began pursuing WTO membership, which was supported by the Clinton administration because it wanted China to lower its tariffs and open its markets to U.S. manufacturers while adhering to global trading rules. In 2001, China joined the WTO. 97

Some considered China’s entry a win for U.S. consumers, because it cut the costs of some goods. Businesses also cashed in, because China’s markets opened to U.S. agricultural and other exports, such as airplanes. For China, the new U.S. market spurred it to become a global manufacturing powerhouse. In 2000, for example, the United States exported $16 billion worth of goods to China and imported $100 billion. By 2024, those figures ballooned to $143 billion in exports and $439 billion in imports. 98

But not everyone was pleased.

Labor unions, especially those representing manufacturing workers, opposed China’s entry. They worried that cheaper imports would mean fewer American factories and jobs. By one estimate, almost 6 million U.S. jobs disappeared between 1999 and 2011, with roughly 1 million jobs in manufacturing and 2.4 million tied to Chinese competition. But, because automation was also eliminating many U.S. jobs, economists have long debated just how many American jobs were lost due to China’s growth. 99

After China joined the WTO, global supply chains shifted and became more complex, as China and other countries, such as Mexico, built up manufacturing by paying lower wages. As a result, the wage premium for American factory workers versus non-manufacturing jobs all but disappeared in 2006, according to the Federal Reserve. 100

Tariffs made a comeback during the George W. Bush administration. In 2002, Bush implemented tariffs ranging from 8 percent to 30 percent on steel imports that were to last for about three years, except for those from Canada, Israel, Jordan and Mexico, which were excluded. Job losses tied to higher steel prices totaled about 200,000, more than the 187,000 employed in the steel industry itself, according to one study. 101

President Barack Obama also used tariffs. In 2009, he levied a 35 percent tariff on Chinese tires through 2012, aiming to save jobs and combat alleged unfair competition from Chinese makers. While it preserved an estimated 1,200 American jobs, PIIE found that related industries lost 3,700 jobs, and consumers paid $1.1 billion in higher prices as a result. The Chinese retaliated by placing tariffs on U.S. chicken, which the administration estimated lost farmers about $1 billion. The United States won its case defending the tire tariffs against China before the WTO. 102

The Obama administration also signed an agreement to enter the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade agreement designed to encourage trade among the United States and 11 other nations: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam. The United Kingdom joined in 2024, and South Korea and Ukraine are considering applying. Although the Obama administration signed the agreement, Congress never ratified it, and the Trump administration withdrew from it in 2017. The agreement was renamed The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in 2017, and the United States is not a member. 103

Trump, a longtime admirer of tariffs, began pursuing protectionist policies after taking office in January 2017. The next year, he launched a trade war, posting on social media that “trade wars are good, and easy to win.” He imposed tariffs, mostly on Chinese goods, some at heights not seen since the Smoot-Hawley era. 104

In 2018 the White House imposed 30 percent tariffs on imported solar panels, mostly from China, then the United States’ largest trading partner. The tariffs escalated in a tit-for-tat exchange between the two nations, with China raising its levies on U.S. products and halting purchases of American corn, soy and pork. The United States ultimately imposed tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese imports. U.S. importers of those goods scrambled to shift production to other countries. The White House also banned telecom company Huawei from buying U.S. components due to national security concerns. 105

In 2020, the Trump administration renegotiated NAFTA, renaming it the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). The new agreement includes, among other things, a section on digital trade, which didn’t exist when NAFTA was negotiated. It also requires 75 percent of automobile components be made in one of the three countries and added enforcement provisions for labor between Mexico and the other two countries. 106

In January 2020, the United States and China announced a deal to slow the trade war. Before that, however, the tariffs and resulting trade war had cost 245,000 American jobs and slashed incomes by roughly $675 per U.S. household, according to one estimate. 107

After taking office in 2021, President Joe Biden retained most of Trump’s Chinese tariffs and removed some Trump had placed on allies, such as steel and aluminum tariffs on EU countries. The tariff rate on Chinese products reached almost 21 percent by the end of his administration, up from 19 percent when he took office. 108

Current Situation

Even ahead of his April broad announcement and pause, Trump, in February and March, used his authority under the IEEPA to levy tariffs on China and traditional allies, including Canada and Mexico. Two days after announcing the Canada and Mexico tariffs, on March 6, he announced an exemption for an array of products that fall under the USMCA agreement under an indefinite pause. The administration said it was using these tariffs to pressure allies and rivals to do more to prevent illegal drugs, such as fentanyl, and unauthorized immigrants from entering the United States. 109

The White House also announced 25 percent tariffs on imported steel and aluminum, later raising that percentage to 50 percent, including imports from the EU and the United Kingdom. 110

In March, Trump levied a 25 percent tariff on all imported autos and certain auto parts, among other new tariffs, sparking retaliation or threats of retaliation from the EU, China, Canada and Mexico. 111

Then-Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau threatened retaliatory tariffs on $100 billion in imports of American goods, enraged at a policy that came on top of other geopolitical shocks to Canadians from the second Trump White House, including threats to annex the country into the United States.

“Today the United States launched a trade war against Canada, their closest partner and ally, their closest friend,” Trudeau said. “At the same time, they are talking about working positively with Russia, appeasing Vladimir Putin, a lying, murderous dictator. Make that make sense.”

Mexico also announced retaliatory tariffs and negotiated compromises to postpone some levies, as did the EU and China. 112

Tariffs on steel and aluminum and autos, as well as a broad 10 percent levy, remained in effect for EU imports as the two sides negotiated. 113

On April 2, Trump imposed a minimum 10 percent tariff on almost everything the United States imports, with some exceptions, such as cell phones and computers. China faced a higher rate of about 30 percent. On April 9, Trump suspended tariffs above 10 percent until July 9, later extending that date to Aug. 1, to give countries on which the United States imposed high rates time to negotiate deals. 114

On May 29, the day after the Court of International Trade said Trump had overstepped his legal authority under the IEEPA, a federal court in Washington agreed in two similar cases ― one brought by five small companies and the other by a dozen state attorneys general. Echoing the Court of International Trade, the three-judge panel said the IEEPA, which doesn’t mention tariffs, does not give the president “unbounded authority” to enact them.

Experts expect the fight over both IEEPA rulings will end up at the Supreme Court. 115

On June 16, Trump and U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer signed a trade deal that cuts tariffs on the auto industry and eliminates them for aerospace industry imports, finalizing a framework deal reached in May. The United States still needs to decide how much U.K. steel will be exempt from 25 percent tariffs on imports.

The U.K. agreement, signed at the G-7 annual meeting in Canada, marks the first signed by Trump since his April announcement. The G-7, or Group of Seven, includes the leaders of traditional allies Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United States. 116

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the World Trade Organization’s director-general, speaks at a press conference on April 16 in Geneva, to announce the 2025 Global Trade Outlook and Statistics, including “severe negative consequences” to the global merchandise trade due to Trump’s tariffs. (AFP/Getty Images/Fabrice Coffrini)

The agreement comes after another framework pact with China earlier in June. That handshake deal sets 55 percent tariffs on imports of Chinese goods. Other details about the agreement are scant. 117

China also agreed to provide rare earth elements ― metals used in computers, batteries and magnets ― to U.S. companies for six months after reducing such sales in April. China currently controls about 70 percent of rare-earth sales worldwide and refines about 90 percent. 118

“What’s become clear in the last few weeks is that this rare-earths issue has got real leverage for Beijing,” said Christopher Wood, who leads strategy for global equities at the investment bank Jefferies in Hong Kong. 119

In April, when the White House paused its sweeping tariffs on most nations for 90 days, Trump trade advisor Peter Navarro said, “We’ve got 90 deals in 90 days possibly pending here.” 120

As the 90-day deadline approached in July, Trump extended it to Aug. 1, while the White House continued to negotiate trade deals with 18 trading partners. 121

At the G-7 Summit, the new Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney said the United States and Canada are aiming to reach a new trade agreement in 30 days. However, Trump announced in late June that he was cutting off negotiations with Canada over its Digital Services Tax, which is about to go into effect. In response, Carney announced that the country was walking back the tax. 122

Canada, unlike the EU, hasn’t announced retaliatory tariffs to Trump’s doubling of steel and aluminum levies to 50 percent. The EU has prepared $24 billion in retaliatory tariffs for the steel and aluminum hikes, including on motorcycles, poultry, soybeans and other products. 123

On July 2, the White House announced a tariff deal with Vietnam, in which the United States will charge 20 percent duties on Vietnamese imports and 40 percent for goods from other countries, including China, that pass through Vietnam en route to the United States. In return, goods made in the United States will be able to enter Vietnam duty-free. The 20 percent tariff is less than the 46 percent that Vietnam initially faced under the April announcements. 124

On July 15, Trump announced a trade agreement with Indonesia, which Indonesia President Prabowo Subianto confirmed the next day. Under the agreement, Indonesian goods imported into the United States will be taxed at 19 percent, down from Trump’s declaration of 32 percent tariffs in April. Indonesia will also purchase Boeing planes, energy and farm products from the United States, though further details were not yet disclosed. 125

As the July 9 deadline for paused tariffs approached, the Trump Administration had announced just three agreements, rather than 90 deals in 90 days as promised. Then, starting on July 7, the administration sent letters to more than 20 countries, mostly in Asia, North Africa and Eastern Europe, noting its intention to impose tariffs on Aug. 1, mostly at rates similar to those announced in April. 126

On July 8, Trump threatened to put a tariff of up to 200 percent on imported pharmaceuticals, adding he would give companies time “to get their act together.” The long-awaited announcement may be a good thing for the industry “because tariffs will not be implemented immediately … and it is unclear if the administration will follow through in the future,” said David Risinger, an analyst with Leerink Partners, a firm that advises investors. The top countries from which the United States imports drugs include (in order by value): Ireland, Switzerland, Germany, Singapore, Belgium, India, Italy, Japan, the U.K., China and the Netherlands. 127

On July 9, the EU said it was making progress toward a “framework” agreement with the United States in hopes of avoiding higher tariffs but has readied retaliatory tariffs in case negotiations fall apart. Trump, meanwhile, has threatened imposing higher tariffs effective Aug. 1 if no agreement is reached. 128

Small businesses, such as Liquid Hardware, owned by Stephen Kitto of Victor, Idaho, could go under if tariffs remain high. Kitto imports his product from a manufacturer in China, and says he has enough inventory to last through the fall, but after that, a 145 percent tariff would mean the retail price could double or more. (Getty Images/Natalie Behring)

Trump also announced a broad, 50 percent tariff on copper imports, effective Aug. 1. Copper is a widely used metal in everything from electrical wiring to household appliances and plumbing. Prices for copper immediately jumped 13 percent. The proposal may be aimed more at striking deals with major copper suppliers including Canada and Chile, rather than an actual intent to impose the tariffs, said UBS chief investment strategist Kurt Reiman. Still, the new round of threats prolonged uncertainty for businesses, markets and consumers. 129

The administration also announced its intent to levy a 50 percent tariff on goods from Brazil, a nation with which the United States runs a trade surplus, not a deficit, like most other countries. Trump said in a letter he posted on social media that the rate is in part to protest the ongoing prosecution of former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, a Trump ally on trial for his role in an alleged coup to overturn his 2022 reelection loss. Brazil’s current president, Luiz Inacio Lula de Silva, said, “Brazil is a sovereign country with independent institutions that will not accept being lectured by anyone.” He also said his country would respond in kind with reciprocal tariffs on U.S. goods if the United States imposes the levies. 130

On July 10, Trump revived his focus on Canada, announcing a 35 percent tax on imports effective Aug. 1, again blaming the increase on illicit drugs entering the United States from the north. Goods controlled by the USMCA wouldn’t be subject to the new levy, but that could change, a White House official told The Wall Street Journal. The two countries had set a deadline of July 21 to conclude negotiations to lower tariffs. 131

The EU, which negotiates for 27 European nations, estimates U.S. tariffs now on hold represent about 70 percent of the bloc’s exports to the United States. 132

Mexico began talks with the United States on July 11, creating a working group to discuss security, migration and economic issues, according to Mexican Economy Minister Marcelo Ebrard. “We believe, based on what our colleagues discussed yesterday, that we will reach an agreement with the United States government and that, of course, we will achieve better conditions,” Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said. 133

On July 12, Trump posted two more letters on social media, threatening both Mexico and the European Union with a 30 percent tariff on all goods into the United States on Aug. 1. 134

Imposing such tariffs “would disrupt essential transatlantic supply chains, to the detriment of businesses, consumers and patients on both sides of the Atlantic,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said, adding that the bloc would continue to negotiate but would impose “proportionate countermeasures if required.” 135

The European Union now has a “new sense of urgency” to accelerate trade agreements with countries other than the United States, EU chief trade negotiator Maros Sefcovic said on July 13. The EU is considering possible coordination with Canada and Japan, among other nations, Bloomberg reported.

“We need to explore how far, how deep we can go in the Pacific area,” said EU competition chief Teresa Ribera. She noted the EU’s ongoing trade discussions with India are expected to end this year. 136

Trump said Japan is being “tough” in negotiations. The country is coping with a 25 percent global tariff on autos that Trump imposed in April, a move which Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba called a “national crisis.” Japan was also subject to a 24 percent tariff under the April 2 IEEPA levies. In June, Japan moderated its call for a total repeal of the auto tariff during meetings in Washington. 137

In a July 7 White House news conference, Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt holds up a letter from President Trump to the Japanese prime minister notifying him of the administration’s intention to impose tariffs on Aug. 1, after a pause of several months. Similar letters were sent to more than 20 other countries. (Getty Images/Xinhua News Agency/Hu Yousong)

Trump said on July 14 that he would punish Russia by imposing secondary tariffs targeting its trading partners if it didn’t end the war in Ukraine within 50 days. Those tariffs could be as high as 100 percent, he said during a meeting with the secretary-general of the North American Treaty Organization, Mark Rutte. The administration had not previously targeted Russia in its country-specific tariffs. 138

Also on July 14, the White House withdrew from a decades-long agreement that prevented tariffs from being levied on tomatoes from Mexico as long as they were kept below a certain price level and imposed a 17 percent import tax. “Mexico remains one of our greatest allies, but for far too long our farmers have been crushed by unfair trade practices that undercut pricing on produce like tomatoes,” Howard Lutnick, the secretary of commerce, said. “That ends today. This rule change is in line with President Trump’s trade policies and approach with Mexico.” 139

On July 22, Trump said the United States and the Philippines had reached a trade agreement. The United States will charge 19 percent for imports from the country while U.S. exports to the Philippines will not be subject to tariffs, and the two countries will cooperate militarily. 140

Also on July 22, Trump announced a deal with Japan to lower tariffs on imported Japanese goods, including autos, to 15 percent, down from the proposed 25 percent. Japan, in turn, will remove barriers for imports from the United States for auto and agricultural goods and plans to invest $550 billion in the United States. 141

“Nobody knows where anything’s going to land, and so, that’s really disruptive [in the] short term,” says Erica York, vice president of tax policy at the Tax Foundation, a right-leaning think tank. “At some point, things have to land somewhere, and they’re probably going to land at higher tariff rates than existed in January,” York says. “That means higher tax burden on imported goods, which will reduce investment, reduce productivity, ultimately reduce economic output compared to where it would have been otherwise.”

A federal appeals court is scheduled to hear arguments at the end of July on whether the Court of International Trade’s ruling that Trump overstepped his authority under the IEEPA by levying a broad swath of tariffs will be upheld. The Supreme Court, if it decides to take Learning Resources’ case, will not hear it until the fall and wouldn’t rule on it until next year. Over the longer term, however, Trump’s antagonistic approach to allies and adversaries alike may have shaken confidence in the United States, starting with the U.S. dollar as a financial bedrock for global transactions. “[F]or these very immediate, and very small, monetary gains, the government has potentially triggered a much bigger process that will eliminate some of the benefits the country has enjoyed,” said Oleg Itskhoki, an economics professor at Harvard University. “[Y]ou can call French President Emmanuel Macron or U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer to negotiate on tariffs. But you cannot call up the financial market and tell it to have faith in the dollar.”

That doesn’t mean the United States will lose its place as the center of the financial and economic world just yet, he said, but “it is clear that the tariffs marked the start of some sort of realignment.” 142

Diplomatic relationships have also been upended, a shift that will last years into the future, leaving many longtime allies questioning how to best deal with the United States going forward. In Asia, for example, many countries have geared their economies toward supplying the United States as a way of strengthening diplomatic relationships.

“Many in Asia are going to ask, ‘Is this how the U.S. treats its friends?’” said Manu Bhaskaran, chief executive of Centennial Asia Advisors, a research firm. “Will there be permanent damage to American standing and interests in Asia and elsewhere through these crude threats and unpleasant language?” 143

Public sentiment among U.S. allies has been damaged by Trump’s approach, said Jonathan E. Hillman, a senior fellow for geoeconomics at the Council on Foreign Relations, a New York-based think tank. Citing an Ipsos poll of 29 nations on their publics’ attitudes towards Trump’s economic policies, he said: “This shift in public sentiment encourages elected leaders to ‘derisk’ from the United States.” Macron, for example, has called for what he calls European strategic autonomy while “pushing for European replacements to U.S. cloud services, satellites and fighter jets, among other areas.” It’s too early to measure how Trump’s tariffs might affect national security, and “any benefits may well take longer to materialize, given that supply chains can take years to adjust,” Hillman said. “But in the meantime, mounting costs underscore the need for greater clarity of U.S. objectives, measurable targets and exemptions to minimize unintended consequences.” 144

Wendy Cutler, vice president at the Asia Society Policy Institute, said, “[I]n some ways, we’re missing the larger picture. And I worry that these countries are going to look at us differently and treat us differently going forward, even if they’re able to reach a deal on August 1. This has not been a great experience for them.” 145

Do Trump’s tariff policies create conditions for manufacturing growth in the United States?

Here are some issues to consider regarding U.S. tariff policy:

1770s-1890s

The Tariff Act imposes levies, mainly on imported agricultural goods, as the principal source of revenue for the new U.S. government.

Congress sharply raises tariffs on imported goods to protect Northern industries in an act dubbed the “Tariff of Abominations” by Southern agricultural interests.

As the Civil War approaches, the U.S. prepares to finance it by raising tariffs.

Ohio Rep. William McKinley, a Republican, authors a bill raising tariffs to their highest levels yet. Later, as president, he will temper his stance.

1900s-1940s

The U.S. Tariff Commission (later renamed the United States International Trade Commission) is established to set tariff levels.

The Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act raises tariffs and gives the president the power to raise or lower any tariff by 50 percent.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act imposes some of the highest protective tariffs in U.S. history, exacerbating the Great Depression.

The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act allows the president to temporarily raise or cut U.S. tariffs up to 50 percent of the levels under Smoot-Hawley in exchange for concessions by other nations. It is subject to renewal every three years.

The United States and other nations negotiate the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) to promote open trade in the postwar world.

1950s-1990s

Multinational treaties, government organizations expand global trade.

Six European nations form the Common Market (forerunner of the European Union), which removes international trade barriers.

President John F. Kennedy signs the Trade Expansion Act, giving the White House the power to lower or impose restrictions on imports and negotiate with trading partners.

President Richard M. Nixon declares a national emergency and imposes a temporary 10 percent tariff on top of standard dues for all imports as part of a set of economic measures dubbed the “Nixon Shock.”

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) eliminates most tariffs between Canada, Mexico and the United States.

GATT becomes the World Trade Organization and develops mechanisms to resolve trade disputes.

2000-2025

U.S. teeters between free trade and protectionism.

China is admitted to the WTO.

President Barack Obama imposes a 35 percent tariff on Chinese tires through 2012. China retaliates with a tariff on U.S. chicken.

The Obama administration negotiates a 12-nation trade pact called the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), but Congress never ratifies it.

Trump, in his first term as president, ends the TPP and begins a new era of protectionism which will see tariffs on goods including solar panels, washing machines, steel, aluminum, and an array of Chinese imports.

President Joe Biden keeps most of Trump’s China tariffs, with some adjustments, while adding new restrictions on microchips.