Can the magic be removed from the mushroom — and should it?

Brian could taste the classical music playing. His tongue was alive with the vibrations as the ceiling rippled. Sitting in a comfortable chair in an Airbnb in the Midwest, he had taken the hallucinogenic drug psilocybin, his therapist beside him as a guide, after exhausting conventional treatments for his complex post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I was in a suicidal, no-tomorrow state,” he said later, describing the debilitating depression, panic attacks and night terrors that had upended his life for over two years. “I couldn’t work. I could barely function.”

Over the course of several hours during that first psilocybin session, Brian (who spoke on the condition of anonymity using a pseudonym) had visions of the adults who had harmed him as a child, harm that contributed to his PTSD. Looking inward, Brian saw each transformed into a suffering kid who had themselves been hurt or abused. “I could see that I was hurt by this wounded child, which made forgiveness easier,” he said.

Waves of deep emotional pain he hadn’t fully felt before shook his body, at times to the point of vomiting. In a later session, he envisioned several people from his life who had died by suicide, connecting to their unique pain and allowing him to fully grieve. For each person, “it felt like I was crying for both of our wounds and healing them,” he said.

These experiences, and talking through them with his therapist and a support group, brought Brian profound relief — relief of the sort that antidepressants, anxiety medication, talk therapy and even the trauma therapy known as EMDR hadn’t produced.

He is one of a growing number of Americans with persistent mental illness who are looking to psychedelic drugs (which are still largely illegal) when traditional therapies fail. A flurry of research into the healing potential of psychedelics has shown these substances, which trigger highly altered mental states characterized by an expansion of consciousness, can provide rapid and enduring relief for depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, addiction and end-of-life anxiety when guided by a trained therapist.

Neuroscientists and psychiatrists think the drugs work by rewiring brain circuitry, but they are increasingly divided on a fundamental question: Do the apparent benefits of these mind-bending substances stem from the “trip” itself? Or might it be possible to strip away this experience while retaining the neuroplastic power of psychedelics, to design a drug that sparks similar brain changes, but without the experiential baggage?

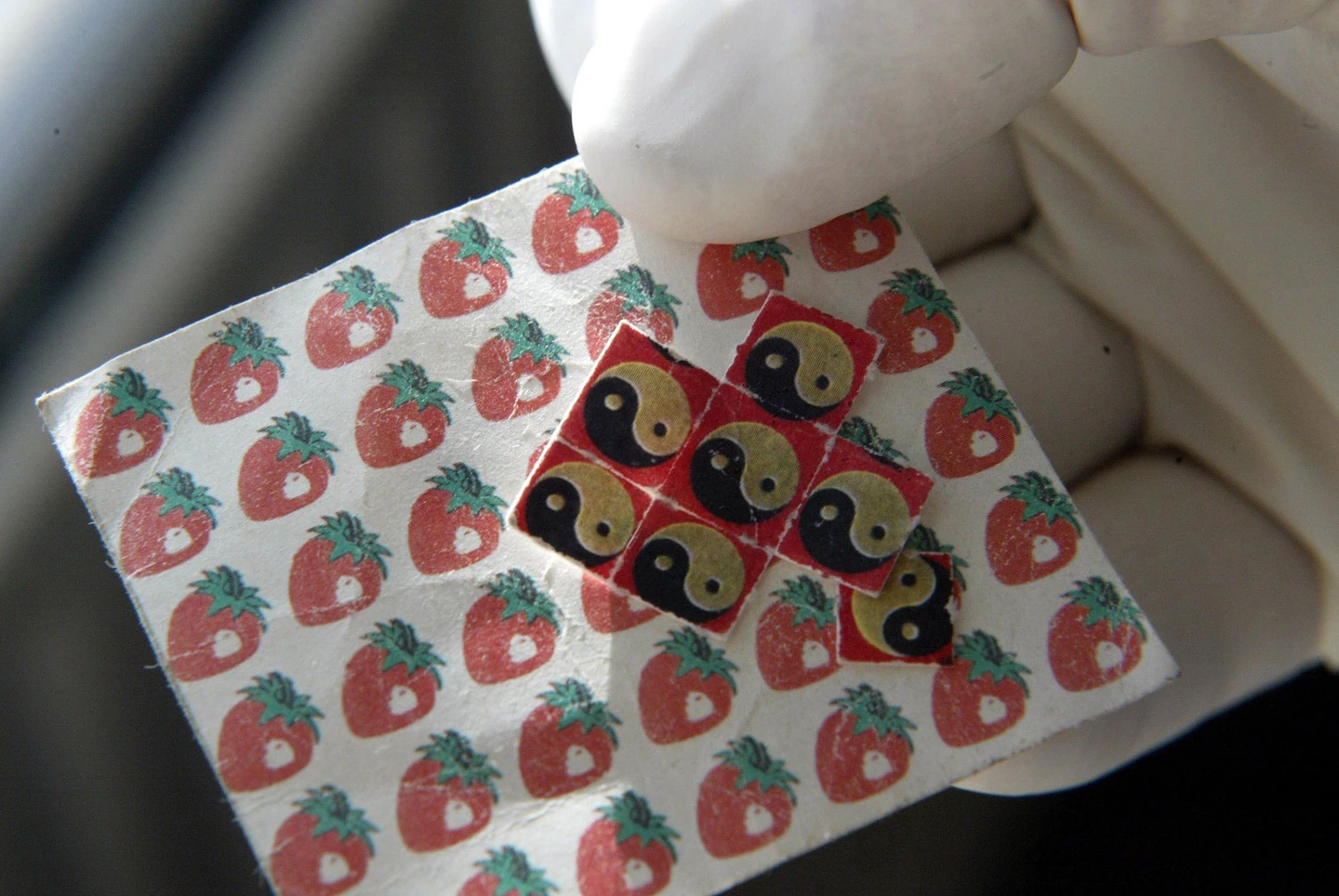

Finding the answer is becoming more urgent as evidence stacks up supporting therapeutic use of the drugs. Already, a cottage industry of psychedelic influencers has sprung up to promote “microdoses” of LSD, and underground therapists take clients on guided trips using psilocybin — derived from “magic” mushrooms — or MDMA, also known as ecstasy or molly. Some experts even predict that the Food and Drug Administration will approve the latter pair of drugs for use by therapists within a few years.

If an intense, supported experience like Brian’s is needed, then psychedelic medicine’s reach will be limited. “We’ll never have enough certified psychedelic psychotherapists to treat the at-risk population in the world,” said Bryan Roth, a pharmacologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Therapeutic sessions can cost hundreds or thousands of dollars, and the drugs, which include psilocybin, mescaline and LSD, also carry risk of a “bad trip” that can leave lasting psychological damage, especially for those with a history of psychosis.

If the psychedelic experience is extraneous, however, a mere sideshow to the neuroplastic magic psychedelics work, researchers and drug companies might develop a more scalable — and potentially cheaper — product. Proponents of designing straight versions of psychedelic drugs argue it could make their benefits more widely available, better able to meet the tremendous demand for better mental health treatment. Many, Roth included, are already racing to devise “tripless” psychedelics, some of which could be tested in humans as soon as this year.

“I have no doubt that psychotherapy is essential for people to have an optimum experience. I don’t think anybody would debate that,” said Roth. “The big question is to what extent does that contribute to the ultimate therapeutic effect of the drugs?”

Quite a lot, according to other experts who suspect the experience itself is the crucial catalyst for lasting change. “I just find it implausible that you could see benefits many months after a single experience without engaging with higher-level neurobiological processes like thought and language and shifts in cognition,” said David Yaden, a psychology researcher at Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research. “But I’m fully interested in being proven wrong.”

Tantalizing evidence

Psychedelics burst into modern science in 1943, when Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann ingested a chemical he’d synthesized years earlier — lysergic acid diethylamide, now known as LSD. The chemist’s surroundings began to dissolve and furniture assumed terrifying forms as Hofmann experienced the first bad acid trip. But later, feelings of immense well-being and gratitude replaced the terror, and Hoffman saw the world in a new, kaleidoscopic light. He continued experimenting with LSD, ushering in a wave of research into the drug and other psychedelics that Indigenous people have used in cultural and spiritual practices for generations.

Large doses of the drugs have shown remarkable promise in treating a variety of mental illnesses, and for decades the psychedelic experience itself seemed key. Such experiences can vary widely but are often characterized by profound changes in perception, seeing patterns of light, intense inner imagery or external hallucinations, and overwhelming feelings of connection, insight and a dissolution of the self. Afterward, many report a wholesale and enduring shift in their mental state, as if the experience did something to shake them out of negative thought patterns and behaviors.

“The characteristic acute subjective effects are fairly unusual compared to many other psychoactive substances,” said Yaden. “That led to the assumption that the acute subjective effects must be what’s driving the therapeutic effects.”

Those therapeutic effects have become clearer over the past couple decades, as psychedelic research resumed in earnest after a long, war-on-drugs-induced hiatus. While many studies are small, psychedelics show real promise against conditions that are hard to treat with what’s available.

Just two large doses of psilocybin alleviated depression in 75 percent of participants one month after treatment and 58 percent a year later, according to a recent study of 27 patients. When tobacco smokers trying to quit underwent a similar paradigm, 80 percent reported success, significantly greater than the 35 percent associated with other strategies. MDMA can take the sting out of painful memories and may soon be approved by the FDA for PTSD. And psychedelics can help terminally ill cancer patients come to terms with death, substantially easing anxiety and depression for about 80 percent of participants in a recent clinical trial.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy “can almost fundamentally change someone’s personality,” said Katherine Nautiyal, a neuroscientist at Dartmouth College. “Things people previously thought were unchangeable now have the capability of being changed drastically, and long-lastingly, with just one treatment.”

Neuroscientists like Nautiyal are just cracking open how psychedelics reshape the brain in ways that might underlie, or at least contribute to, these profound effects.

Remodeling the brain

“Psychedelics do really interesting things in the brain,” said David Olson, a chemist and director of the University of California, Davis, Institute for Psychedelics and Neurotherapeutics. “In addition to producing these really profound subjective experiences, they also physically change the structure of neurons,” he said. Specifically, they spark new growth and connections in the prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain that atrophies in many neuropsychiatric diseases. The drugs seem to do this by binding to a receptor inside neurons called the serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2AR).

“There’s a lot of literature dating back several decades that has shown atrophy of the prefrontal cortex is a hallmark of many diseases, like depression, PTSD and substance-use disorder,” said Olson. That atrophy may lead the brain to get “stuck” in negative patterns that make it difficult to regulate emotions. Reversing that atrophy by stimulating new growth, the thinking goes, might alleviate symptoms by normalizing communication with other parts of the brain that regulate fear, motivation, reward and cognition.

“It turns out this is how a lot of our antidepressant medications currently work, they’re just not great at it,” said Olson. Laboratory studies show that SSRIs like Prozac or Zoloft must be taken daily for several weeks before neuroplasticity kicks in. Psychedelics work much faster and more intensely. A single large dose can spur new neuron growth in laboratory mice within hours, and those changes persist long after the drug clears the system.

Since both antidepressants and psychedelics help remodel parts of the brain (albeit in different ways) and both can alleviate symptoms, but only psychedelics spark hallucinatory experiences, it follows that the psychedelic experience isn’t necessary for neuroplasticity.

That corollary poses a tantalizing question to researchers.

“Is it possible to make a druglike compound that has the rapid, robust and enduring neuroplastic effects of psychedelics without the psychedelic experience?” asked Roth. Such a drug could revolutionize mental health treatment for the 100 million people worldwide who suffer from treatment-resistant depression, or those with other recalcitrant mental disorders.

“Right now, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is for the 1 percenters,” said Olson — people who can afford to pursue treatment underground, which can cost hundreds to tens of thousands of dollars, and dedicate many hours to therapy sessions before, during and after treatment. A tripless pill that could be taken once, without the need for supportive psychotherapy, could in theory reach many more people.

To be clear, scientists don’t fully understand the neural pathways that underlie the psychedelic experience, and whether these are the same as or different from those that determine neural growth. But recent studies suggest it may be possible to disentangle the two, and scientists are racing to develop and test candidates.

There are several different strategies. In Olson’s lab, researchers start with existing psychedelic molecules, like psilocybin or MDMA, and tweak their structures ever so slightly in hopes that they’ll produce a molecule that is therapeutic but not hallucinatory. They screen these molecules in stressed-out mice, looking to see whether the drugs impact a mouse’s efforts to stay afloat when dropped into a water tank (a classic technique in depression studies: Sad mice give up sooner than content ones). Because scientists cannot ask a mouse if it’s tripping, they measure an unusual behavior — called the head twitch — that mice tend to exhibit when given compounds known to produce hallucinations in humans.

“Are the mice having hallucinations? Who knows,” said Olson. “But the [head twitch] test seems to be very predictive.” This approach has already yielded some promising molecules, including two slated to go into human trials later this year, said Olson. “We won’t truly know whether these compounds are non-hallucinogenic until we give it to a person. Then we’ll have the answer pretty quickly.”

Other labs are making progress too. Last year, scientists in China tweaked certain antipsychotic drugs to bind differently to the 5-HT2AR receptor and found that the new molecule alleviated behavior associated with depression in mice without apparent hallucinogenic effects. And Roth and colleagues recently developed a molecule based on LSD that showed similar promise.

Whether these candidates work as well as actual psychedelics won’t be known for several years, as it takes time to conduct thorough clinical trials. Even if they’re effective, such drugs may come with their own unique risks.

“We don’t know whether it would be risky to put someone in a highly plastic state and have them just walk around without therapeutic oversight,” said Yaden. There’s also no guarantee these drugs will be cheap, especially as some companies look to monetize psychedelics.

While Yaden welcomes research into non-hallucinogenic psychedelics, he and others remain skeptical that you can take the magic out of magic mushrooms without losing something profound.

The case for experience

Aside from the intuitive sense that psychedelics drugs’ unusual healing potential likely stems from the unusual experiences they spark, some research suggests that the tripping itself does matter.

“There’s no direct evidence on the question,” said Nautiyal. For that, researchers would have to conduct a trial where people get psychedelics while under anesthesia, presumably not experiencing anything, and see if they get the same therapeutic benefit, she said. Such experiments have been proposed but never done. “But there’s strong correlational evidence that the intensity of the subjective experience correlates with long-term clinical efficacy.”

Specific kinds of trips confer the greatest benefit. “Those who feel a connectedness, oneness, unity tend to have better therapeutic responses weeks or months later,” said Yaden. “Insight also predicts therapeutic response,” he said, with people who say the experience led them to see themselves or their issues in a new light reporting the greatest long-term change.

For many, these experiences rank among the most meaningful of their lives. “There’s a well-replicated finding that two-thirds of participants in psilocybin conditions of studies will say that the experience was in the top five most meaningful experiences of their lives.”

There is a dangerous flip side to psychedelics’ power, however, especially when people take the drugs without support from a therapist. “If this is such an intense experience, one that can be the most meaningful of some people’s lives, imagine that in reverse,” said Julian Evans, a researcher at Queen Mary University of London. “Imagine this being one of the worst experiences of your life. That’s going to leave a mark.”

Evans himself had such an experience at 18, when a recreational LSD trip turned south. “I was with people I didn’t know well and became very self-conscious and paranoid,” he said. “I developed this intense fear that I’ve done permanent damage to myself, and that lingered after I came down.” For six years afterward, he struggled with social anxiety, panic attacks, and a kind of dissociation from his body and himself.

Those kinds of trips are relatively rare, but Evans and his colleagues at the Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project are trying to understand their prevalence and how to help. “There’s so much positive news around psychedelics, people who have bad experiences may not feel like they can talk about it,” he said. “Psychedelic therapy, like any form of medical intervention, has adverse side effects; we’re trying to learn about them and figure out how to mitigate them.”

Well-trained therapists are crucial for minimizing risk of bad experiences, but they’re also crucial for making sense of good ones. The meaning individuals ascribe to psychedelic experiences — the processing of painful memories, the acceptance of death or the crystallization of a new, healthier perspective on life — doesn’t just stem from the experience itself. It’s constructed through dialogue with a trained therapist before, during and after the experience.

“It’s the relationship with a guide or a therapist, who can be with you, talk with you, listen and relate and help you connect with yourself again,” said Mariya Javed-Payne, director of mental health at the Institute for Integrative Therapies in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, which offers legal ketamine-assisted psychotherapy. “We’re working with [patients] to integrate their experience and hardwire it in so that neuroplasticity that’s available right after a session actually creates wellness,” she said. “Without that, the medicinal benefit just doesn’t last for a lot of folks.”

Learning how to guide a patient through psychedelic-assisted therapy takes time and money. Javed-Payne completed the California Institute of Integral Studies’ nine-month training program, which taught clinical skills, the history and research around psychedelics, and how to guide a psychedelic experience. “It equips you, but like anything it’s not real until you get out there and do it,” she said.

The need for such specialized therapists may constrain how accessible psychedelic-assisted therapy becomes, and experts worry that it may be too expensive to reach those most in need.

Parallel tracks

The ultimate importance of taking a trip, rather than a psychedelic-derived treatment that cuts out the high, may end up varying across ailments or people, experts said, underlining the importance of having more options.

“Sometimes in this debate, people see it as an ‘either-or’ story,” said Olson. “I don’t think that’s the case at all; it’s an ‘and-and’ story,” he said. “Psychiatry is desperate for new treatments, patients are desperate for new treatments, and we really need to be exploring every option possible.”

For terminal cancer patients grappling with existential distress, “my guess is you probably need a subjective experience to really impact how you feel about that diagnosis,” said Olson. “But for run-of-the-mill depression, maybe you can get away with these non-hallucinogenic variants.”

Assuming such tripless psychedelics end up offering some degree of safe and effective relief, the best option may be letting people make informed decisions for themselves. Such pills may open up the promise of psychedelic medicine to those at higher risk for bad experiences, or people who simply don’t like the idea of taking a trip.

“The principle of autonomy is important here,” said Yaden. “Having the option to do both, but allowing people to decide for themself, that would be most ideal.”

For Brian, the experience itself was key. “I’m still shocked at how powerful and healing these journeys were. … I don’t know of any other kind of healing modality that could have allowed me to process so much in such a short period of time.” he said. “But I couldn’t have done it by myself. It can be a confusing way to heal,” he said, crediting his therapist and a psychedelic support group for helping him make sense of the journeys.

Now, “there are lots of days where it doesn’t feel like I even have PTSD,” he said. He’s found a job, a temporary one as he figures out what he wants to do next. “There’s still work to do, I’m not denying that,” he said. But psychedelics gave him traction to keep improving through more traditional means that didn’t help before, like talk therapy.

“When I started this path, there was no hope,” he said. “But now there is hope.”

Thanks to Lillian Barkley for copy editing this article.