Our family once spent a brief interlude in the mid-1990s attending a Unitarian Universalist church. The experience was memorable. We were atypical churchgoers — one genetically and culturally Jewish, one a nominal Protestant educated by nuns, and two young children getting their first exposure to any religion.

I realize now that our quirks made us fit right in. Like America, this Unitarian congregation contained multitudes. You could believe in God, or not. You could have grown up with Christmas carols and candles, or menorahs and “I have a little dreidel,” or nothing at all. You could be straight or LGBTQ.

And you could be Black or any other color. But most often you weren’t. Like America, a nation in a jagged but ongoing quest to live up to its values, the Unitarian church was a work in progress.

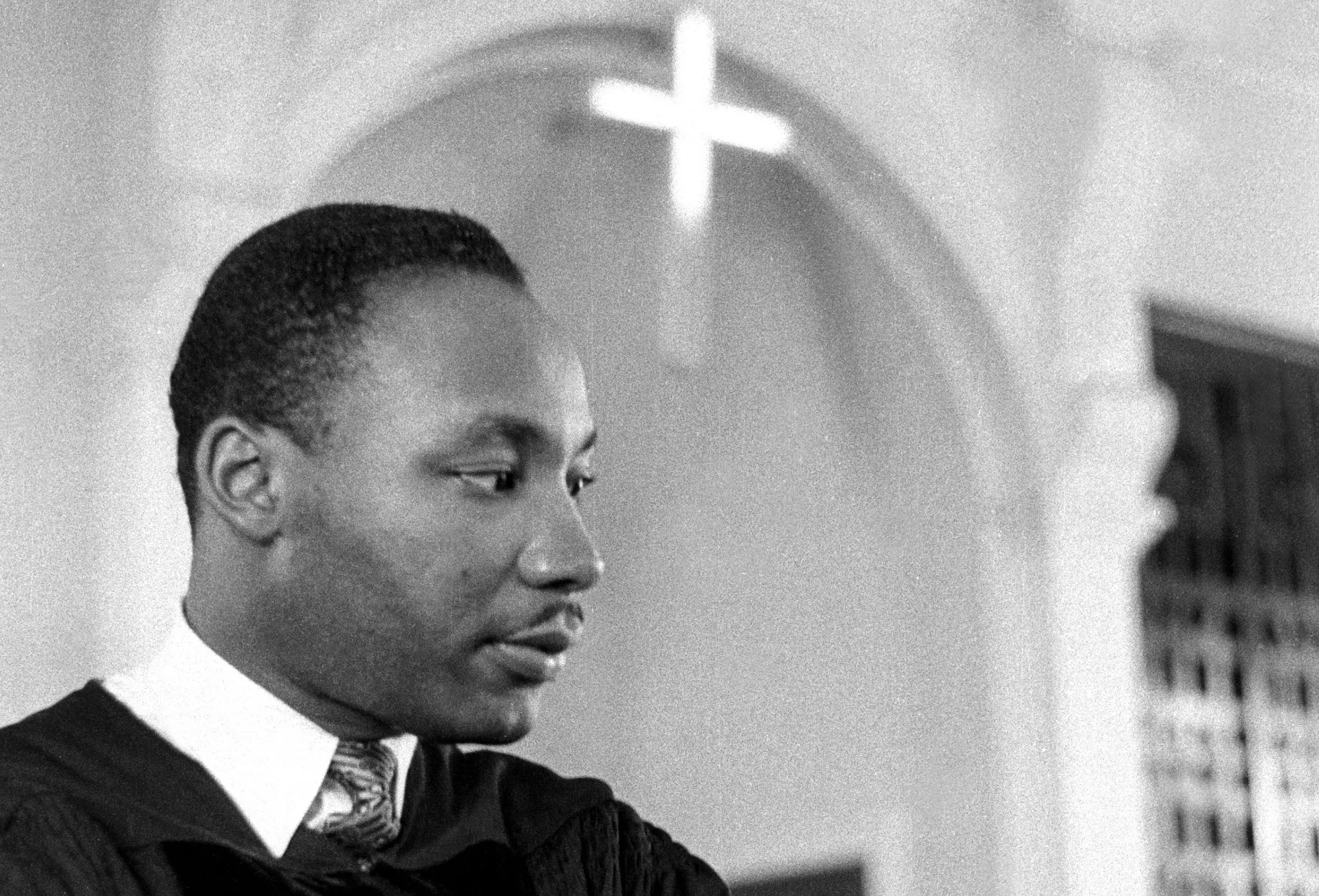

On Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday in 1995, the minister at our suburban Washington, D.C. church — Rev. Roger Fritts — lamented in a sermon called “The Hunger for Diversity” that Unitarian congregations were diverse in almost every respect but race. King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, he said, had inspired him and many others to dream of “many Black as well as white members” in their pews. But more than three decades later, “the membership in most of our congregations remains primarily white. The dream for racial diversity has not come to pass.”

Now it’s been over 60 years since that MLK speech, and even longer since he famously called it tragic that “eleven o’clock on Sunday morning is one of the most segregated hours, if not the most segregated hours, in Christian America.”

So how is that going?

In a national survey of more than 6,600 adults, released last spring by the Public Religion Research Institute, at least three-quarters of white Christians nationally said their churches were mostly white, and about two in ten said their congregations were multiracial.

And what about the Unitarian Universalists? I called to find out.

The Unitarian community is small. There are 1,083 Unitarian Universalist congregations in America with about 151,000 members, according to Suzanne Morse of the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA). About 7% — 77 congregations — are at least 10% Black, indigenous or people of color. Overall, 83% of congregants identify as white.

This is despite decades of commitment to diversity and a variety of proactive moves since 2017, including more BIPOC leadership, revamped hiring practices, and a $5.3 million donation to Black Lives of Unitarian Universalism, an independent national spiritual support community. “We know that we have not yet achieved the goal of racial equity within Unitarian Universalism, and that it is long-haul work,” UUA executive vice president Carey McDonald told me in an email.

All of these challenges and changes have not been without friction. As the Washington Post asked in a 2018 headline about the “unexplained exit” of a Black minister at All Souls Church Unitarian, “What happens when a church dedicated to fighting white supremacy is accused of it?”

It was a conflicted, unpleasant time, but All Souls, over 200 years old, is still here, still fighting against white supremacy, for diversity and inclusion. In fact, Rev. Bill Sinkford’s sermon this year for the Sunday before MLK Day was called, simply, “Woke.” “The process of awakening is getting a bad name,” he said, adding he would focus on King’s “legacy of moral accountability.”

The centuries-long throughline of tolerance and inclusion was much on my mind when I learned recently that Fritts, my long-ago minister, had spent 2011-2020 as pastor of the Unitarian church in Sarasota, Fla. In 2014, the year Michael Brown and Eric Garner were killed, he and the congregation put up a “Black Lives Matter” banner in front of the church. “We got no negative reaction. Some people were calling us and thanking us,” he told me.

That changed a few years later.

About 2016 or 2017, he said, the church bought a big, orange “Black Lives Matter” banner: “We put that up and for about a week, we got death threats. We decided it wasn’t safe and we took it down,” he said. “The feeling in 2014 was not as polarized as three years later, after Donald Trump was elected and started serving in office.”

Fritts, now retired, left Florida in March 2020, at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, and has not returned. Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) since then has won reelection, become a presidential candidate, restricted teaching on Black history and LGBTQ issues, and remade Sarasota’s New College — once a magnet for unconventional students — into a destination for sports-oriented conservatives keen to attend what DeSantis envisions as the Hillsdale of the south. As of July, over one-third of the New College faculty had left, and in October the school reported that the dropout rate for first-year students had doubled.

Sarasota is a microcosm of the upheaval and division that have shaken U.S. politics in the past decade. Call them “woke,” but the Unitarian Universalists have persevered. By June, the church will have completed the first update to its statement of purpose in 40 years. A new generation is writing the words, Fritts says, but he expects basic Unitarian principles to be the same: “The belief in reason and the belief in love and the belief in the dignity of all people.”

Atheists, agnostics, people who believe in God. Christians and non-Christians. People of any color, LGBTQ or straight. All are welcome, Fritts said. “They can all be together in one place.”

This sounds quaint as Trump talks of enemies and vermin and carnage, and immigrants “poisoning the blood of our country,” and a tiny cadre of House Republicans insists on confrontation instead of compromise. But it also sounds like the America we are taught to believe in: a nation of immigrants, free speech and self-determination, always on a journey toward realizing its founding ideals.

Thomas Jefferson, who admired Unitarianism, predicted in 1822 that “I confidently expect that the present generation will see Unitarianism become the general religion of the United States.” He was wrong. But we still have this country based on the principle, so foundational to the Unitarians, that we can be different and co-exist peacefully. A country where someday, we can all sit at this vast national “table of brotherhood,” as King put it. All together, respectfully, in one place.

Jill Lawrence is an award-winning journalist, opinion writer, and the author of "The Art of the Political Deal: How Congress Beat the Odds and Broke Through Gridlock." A former columnist, commentary editor and editorial board member at USA Today, her previous positions also include national political correspondent for USA Today, managing editor for politics at National Journal and national political writer at The Associated Press.