It will be no easy feat but the race is on to clean up the river and make it safe for the whole community, writes Fran Molloy.

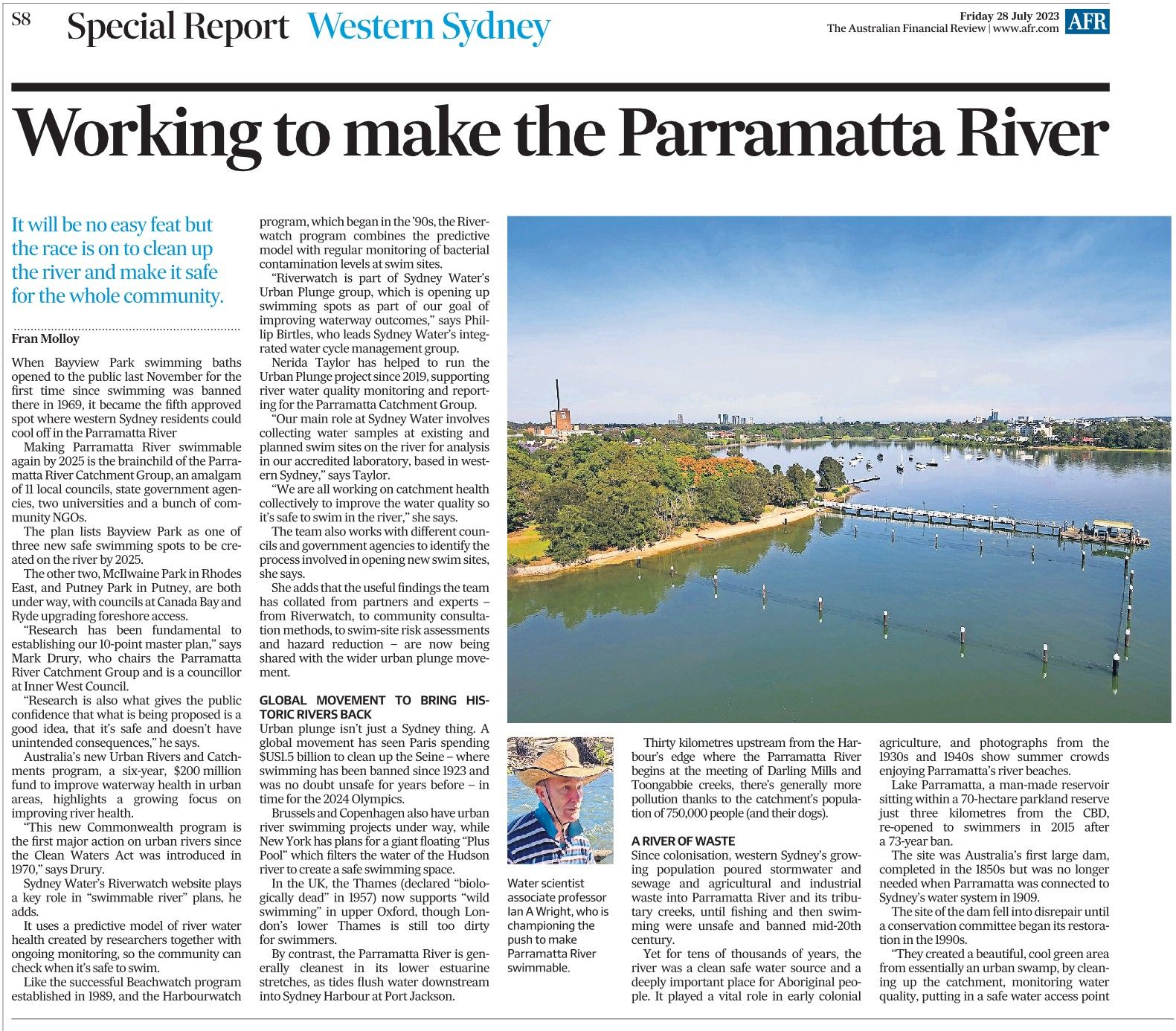

When Bayview Park swimming baths opened to the public last November for the first time since swimming was banned there in 1969, it became the fifth approved spot where western Sydney residents could cool off in the Parramatta River.

Making Parramatta River swimmable again by 2025 is the brainchild of the Parramatta River Catchment Group, an amalgam of 11 local councils, state government agencies, two universities and a bunch of community NGOs.

The plan lists Bayview Park as one of three new safe swimming spots to be created on the river by 2025.

The other two, McIlwaine Park in Rhodes East, and Putney Park in Putney, are both under way, with councils at Canada Bay and Ryde upgrading foreshore access.

“Research has been fundamental to establishing our 10-point master plan,” says Mark Drury, who chairs the Parramatta River Catchment Group and is a councillor at Inner West Council.

“Research is also what gives the public confidence that what is being proposed is a good idea, that it’s safe and doesn’t have unintended consequences,” he says.

Australia’s new Urban Rivers and Catchments program, a six-year, $200 million fund to improve waterway health in urban areas, highlights a growing focus on improving river health.

“This new Commonwealth program is the first major action on urban rivers since the Clean Waters Act was introduced in 1970,” says Drury.

Sydney Water’s Riverwatch website plays a key role in ‘‘swimmable river’’ plans, he adds.

It uses a predictive model of river water health created by researchers together with ongoing monitoring, so the community can check when it’s safe to swim.

Like the successful Beachwatch program established in 1989, and the Harbourwatch program, which began in the ’90s, the Riverwatch program combines the predictive model with regular monitoring of bacterial contamination levels at swim sites.

“Riverwatch is part of Sydney Water’s Urban Plunge group, which is opening up swimming spots as part of our goal of improving waterway outcomes,” says Phillip Birtles, who leads Sydney Water’s integrated water cycle management group.

Nerida Taylor has helped to run the Urban Plunge project since 2019, supporting river water quality monitoring and reporting for the Parramatta Catchment Group.

“Our main role at Sydney Water involves collecting water samples at existing and planned swim sites on the river for analysis in our accredited laboratory, based in western Sydney,” says Taylor.

“We are all working on catchment health collectively to improve the water quality so it’s safe to swim in the river,” she says.

The team also works with different councils and government agencies to identify the process involved in opening new swim sites, she says.

She adds that the useful findings the team has collated from partners and experts – from Riverwatch, to community consultation methods, to swim-site risk assessments and hazard reduction – are now being shared with the wider urban plunge movement.

GLOBAL MOVEMENT TO BRING HISTORIC RIVERS BACK

Urban plunge isn’t just a Sydney thing. A global movement has seen Paris spending $US1.5 billion to clean up the Seine – where swimming has been banned since 1923 and was no doubt unsafe for years before – in time for the 2024 Olympics.

Brussels and Copenhagen also have urban river swimming projects under way, while New York has plans for a giant floating ‘‘Plus Pool’’ which filters the water of the Hudson river to create a safe swimming space.

In the UK, the Thames (declared ‘‘biologically dead’’ in 1957) now supports ‘‘wild swimming’’ in upper Oxford, though London’s lower Thames is still too dirty for swimmers.

By contrast, the Parramatta River is generally cleanest in its lower estuarine stretches, as tides flush water downstream into Sydney Harbour at Port Jackson.

Thirty kilometres upstream from the Harbour’s edge where the Parramatta River begins at the meeting of Darling Mills and Toongabbie creeks, there’s generally more pollution thanks to the catchment’s population of 750,000 people (and their dogs).

A RIVER OF WASTE

Since colonisation, western Sydney’s growing population poured stormwater and sewage and agricultural and industrial waste into Parramatta River and its tributary creeks, until fishing and then swimming were unsafe and banned mid-20th century.

Yet for tens of thousands of years, the river was a clean safe water source and a deeply important place for Aboriginal people. It played a vital role in early colonial agriculture, and photographs from the 1930s and 1940s show summer crowds enjoying Parramatta’s river beaches.

Lake Parramatta, a man-made reservoir sitting within a 70-hectare parkland reserve just three kilometres from the CBD, re-opened to swimmers in 2015 after a 73-year ban.

The site was Australia’s first large dam, completed in the 1850s but was no longer needed when Parramatta was connected to Sydney’s water system in 1909.

The site of the dam fell into disrepair until a conservation committee began its restoration in the 1990s.

“They created a beautiful, cool green area from essentially an urban swamp, by cleaning up the catchment, monitoring water quality, putting in a safe water access point and swimming enclosure, and even lifeguards for busy times,” says associate professor Ian A Wright, a water scientist at Western Sydney University and an ambassador for the Make Parramatta River Swimmable Again program.

He says that rigorous water quality standards set by the World Health Organisation standards and by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council must be met before an area can be declared safe for swimming.

POPULATION PRESSURES

Wright says that Western Sydney’s fast-growing population will continue to put pressure on water quality in the Parramatta River.

“The river suffers from the ‘‘urban stream syndrome’’, in which intensifying urban development means a larger portion of the catchment gets covered by artificial hard surfaces like roads, roofs, footpaths and driveways,” he says.

Stormwater runoff can carry animal and human waste, fertilisers and other chemicals including oil and tyre particles from roads, and it can also wear away concrete water channels and pipes, further polluting creeks and rivers.

Wright says that swamps and bushland and natural growth soak up much of the rainfall, and can filter chemicals and nutrients in runoff water, releasing cleaner water slowly into surrounding creeks.

But when the catchment has less plant growth, rainfall surges far more rapidly and with high energy through concrete pipes and other hard surfaces into the river.

Concrete can change the pH and salinity of fast flowing stormwater and can also put pressure on sewage pipes, which can leak into groundwater.

The solutions can include filtration and more planting in the catchment.

“Making the river safe for swimming is mostly about avoiding microbial disease by reducing the influx of waste from humans and warm-blooded animals like dogs,” he says, adding that water is monitored for bacteria like E.coli and other faecal coliforms.

Mark Drury says that returning swimmers to the Parramatta river has been a major achievement.

“Our urban rivers are the waterways that touch the most people in this country,” he says.

“There’s real community demand to open up the natural swimming spots where they live and make them safe again.”