What are 360s? Grid’s answer to stories that deserve a fuller view.

On medieval European maps, the Arctic was often simply labeled Oceanus innavigabilis — unnavigable ocean — and regarded by scholars as a dark and unforgiving region, home to fearsome mythological creatures and best left alone. Today, those who live south of the Arctic’s climes have a slightly better idea of what’s there, but the region is still often overlooked in discussions of global politics and economics.

But these days, the Artic is getting a lot harder to ignore — and not only because its waters are getting increasingly navigabilis — navigable — for much of the year. Pick a pressing geopolitical issue — from the impact of climate change, to tensions between Russia and the West, to the tenuous state of global trade — and chances are it’s playing out in dramatic fashion on the top of the world.

The war in Ukraine has raised the geopolitical stakes in the Arctic, as it’s the only place on the planet where the United States and Russia are close neighbors. Diplomatic engagement between Russia and the West over Arctic governance has broken down, military assets in the region are growing, and disruptions to the global energy market have highlighted the emerging role of Arctic shipping, which has only become possible in recent years thanks to melting sea ice.

Meanwhile, the recent discovery of a massive deposit of rare earth metals in Arctic Sweden has provided another window onto the region’s future — one involving the region’s vast natural resources. The Arctic has long been both a major source of fossil fuels and the region where the environmental impact of those fuels is most evident. But it’s also likely to be a major source of the materials needed for the world’s “green transition” — and the competition for these resources is heating up.

Given the potential economic benefits of Arctic exploration, it’s little surprise that nations far from the Arctic — notably China — are staking their own claims in the region.

As Sherri Goodman, a former U.S. deputy undersecretary of Defense for environmental security, told Grid, “What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.”

THE BOTTOM LINE

Due to the impact of climate change and the rapid melting of Arctic ice, the geopolitics of the region are shifting rapidly. Given the region’s mineral resources and an increasingly militarized Russia, the Arctic was already an area of increasing geopolitical and economic competition. That competition has remained peaceful to date; but given Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and heightened competition between the U.S. and China, tensions are growing. All of which means a peaceful competition for the Arctic can no longer be taken for granted.

A region transformed by climate change

The Arctic of today doesn’t look like the Arctic of a century ago — that Oceanus innavigabilis on the old European maps. It doesn’t even look the way it did a few decades ago. And the Arctic of tomorrow will look different from the way it does now.

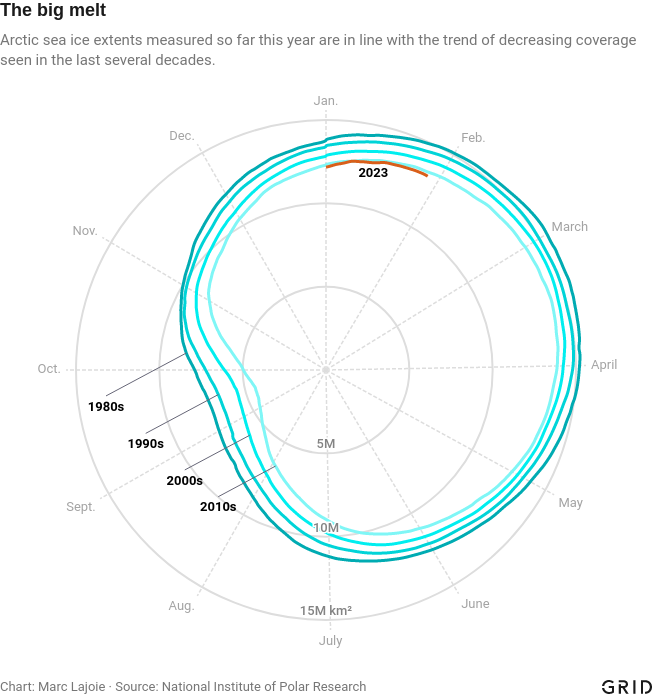

The starkest difference involves changes to the sea ice. The transformation most closely linked to sea-route access and other geopolitical sticking points, Arctic sea ice is undergoing a long and steady decline that is, alarmingly, approaching its apotheosis.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s 2022 Arctic Report Card found that sea ice coverage matched that of 2021, both of which were “well below the long-term average.” The late-summer minimum, when ice covers the least area, has been decreasing steadily, by about 13 percent each decade since 1979, when record-keeping began.

In the summer, it’s now common to find open-water areas around the North Pole itself. Older ice (age is considered a proxy for ice thickness because it accumulates over time) is now exceedingly rare: Ice four years in age or more covered less than half a million square kilometers in 2022, down from almost 3 million in the late 1980s. That’s a staggering drop of more than 80 percent in less than four decades.

To climate scientists, this comes as little surprise. The average surface air temperature in the Arctic in 2022 was the sixth-warmest on record; the 10 warmest Arctic years have all occurred since 2011, and a recent study found that instead of warming at around twice the pace of the global average, as has been commonly cited, the region is actually warming at an astonishing four times the speed of the rest of the world.

“Things are moving faster than we could have expected from the model projections,” said Richard Davy of the Nansen Environmental and Remote Sensing Center in Norway.

Predicting the precise future of the Arctic sea ice is difficult, but studies suggest the end is nigh. One such study from 2020 said it was likely that the Arctic might have an ice-free summer as soon as the mid-2030s, with 2034 considered the likeliest year for that dubious milestone; other research has pegged the date closer to midcentury. This has obvious implications for Arctic shipping lanes and other sea routes; the disappearance of the ice would open a vast area of ocean that only recently began offering any passage at all.

Also relevant to the countries jockeying for Arctic supremacy: The permafrost that makes up much of the far north of Canada, Russia and Alaska is degrading. One 2022 study found that as much as half of the “critical circumpolar infrastructure” — i.e., the land that borders the Arctic — could be threatened by the thawing and eventual buckling of the ground beneath it by 2050. In some far-northern Russian cities, 80 percent of buildings have already sustained damage thanks to permafrost melt.

In its 2022 report card, NOAA didn’t mince words: “Human-caused climate change is transforming the snowy, icy Arctic into a warmer, wetter environment. … It is essential for society to reduce greenhouse gases worldwide.”

In 2007, when a mini-submersible placed a titanium Russian flag on the Lomonosov Ridge, 2.5 miles beneath the North Pole, no one took the stunt very seriously. Several countries have competing territorial claims in the Arctic, and three of them — Russia, Canada and Denmark (which governs Greenland) — claim that the Lomonosov Ridge, which was thought to have significant oil deposits, is part of their continental shelf. This would make it part of their territory under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea. A U.N. commission is tasked with adjudicating these claims based on complex calculations involving the topography and sediment of the ocean floor. Claims can take years to sort out, but generally speaking, most of the Arctic states have been more interested in exploiting the resources within their own unambiguous territories than fighting over the areas that are still disputed. After the Russian flag-planting in 2007, Canada’s foreign minister sniffed, “This isn’t the 15th century. You can’t go around the world and just plant flags and say: ‘We’re claiming this territory.’”

Or perhaps you can.

After Russia annexed Crimea in 2014 and even more so last year, after Russia claimed 15 percent of Ukraine’s territory as its own, the Arctic stunt began to look less silly.

As a result of the war, “we’re suddenly reading Russian intentions in a different way,” Andreas Østhagen, senior fellow at the Arctic Institute, told Grid. “Up until February of last year, there was an idea that, yes, Russia is increasingly a malign or belligerent actor in the Arctic, but that their intentions were to keep the Arctic as a peaceful area for economic development. All those assumptions have been thrown up in the air.”

Raising the heat

Even prior to the war, the Arctic was becoming increasingly militarized.

Under President Vladimir Putin, the Russian government has reopened 50 previously shuttered Soviet-era military bases in the area. Russian facilities in the region house bombers and fighter jets and underground storage facilities for the Poseidon 2M39 — a stealth torpedo powered by a nuclear reactor, designed to evade coastal defenses and deliver a nuclear warhead.

Arctic experts are also concerned the region could see an increasing number of so-called gray zone attacks — actions to disrupt or degrade Western interests in the regions that are never formally acknowledged by Moscow. In a still unexplained incident from January of last year, a little over a month before the invasion of Ukraine, a fiber-optic cable connecting Norway with Svalbard was cut. Svalbard is administered by the Norwegians under a unique treaty that gives other countries, including Russia, residence and commercial rights there — an arrangement that has led to a number of disputes with Russia over the years. The Svalbard incident followed one the previous year in which the cables connecting a network of sensors that monitor submarine activity were also cut.

The post-Ukraine Arctic: preparing for conflict

The war in Ukraine has raised the alarm over Russia’s Arctic intentions.

“The importance of the high north is increasing for NATO and for Canada because we see a significant Russian military buildup,” NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg warned in August. Last March, the U.S. and Canada held joint military drills in the Arctic to test their ability to respond to air and missile attacks. Prior to the drill, Gen. Wayne Eyre, Canada’s top military officer, warned that it was “not inconceivable that our sovereignty may be challenged” in the region, and in October, the Biden administration unveiled a new U.S. Arctic strategy, which foresees increasing conflict in the area with both Russia and China.

While the Russian military currently has its hands full elsewhere, Walter Berbrick, director of the Arctic Studies Group at the Naval War College, told Grid that the risk of confrontation should not be ignored. “Russia’s ground forces have taken a pretty good beating, but its naval and air forces largely remain intact,” he said.

As military tensions rise, the means for managing conflicts peacefully are disappearing. A month after the invasion, the seven other permanent members of the Arctic Council — the intergovernmental body addressing issues in the region — suspended their participation rather than engage with Russia, which was then chairing the group.

The most direct impact of the war on the region has been the decision by Finland and Sweden — both Arctic states — to join NATO. Though their membership bids are currently on hold due to objections from Turkey, if they do eventually join the alliance, Berbrick noted, it will mean that every Arctic country except for Russia will be a member of the alliance.

“If, and likely when, this happens,” he said, “NATO’s border will be less than 150 miles to Russia’s Northern Fleet [near Murmansk] — home to its strategic submarine base.”

The are two great ironies about oil and gas in the Arctic.

The first is that while the burning of fossil fuels across the rest of the globe is the main factor destroying the Arctic environment and forcing displacement and lifestyle disruption among its Indigenous inhabitants, that very destruction is making more of those fuels available — allowing easier drilling and navigation for oil companies.

The second irony is that at the very moment these riches are becoming accessible, much — but not all — of the world is losing interest in them.

In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that the Arctic held 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30 percent of its undiscovered natural gas. At the time, with oil prices near historic peaks, many predicted a coming “Arctic oil rush.”

But soon after that, oil prices fell thanks to the combination of a global financial crisis and U.S. shale production, making drilling even in a warming Arctic not worth the effort. Add to that the growing concerns over the impact of climate change, and it doesn’t look like an Arctic oil rush is materializing — at least not among nations in the West. Last year, when the U.S. government held an auction for oil and gas drilling rights in a massive area off the coast of Alaska — the first such auction in years — it received only one bid.

This isn’t to say that the U.S. has entirely abandoned Arctic drilling. The Biden administration is likely to approve a new ConocoPhillips drilling project on the North Slope of Alaska despite environmentalists’ objections. And a future Republican administration could take even more aggressive steps. But interest is far more limited than it once was.

Even amid recent concerns over energy security and spiking energy prices, the Canadian government decided last month to extend a moratorium on gas and oil drilling in its Arctic waters. The government of Greenland, thought to have vast but undiscovered oil reserves, suspended all oil exploration on the Danish-administered island in 2021.

On the other side of the Arctic, off the coasts of Scandinavia and Russia, where weather and geological conditions make oil drilling easier and most cost-effective, it’s a different story. Norway, which despite its green reputation is Europe’s largest gas supplier and a major crude oil exporter, is set to offer a record number of oil and gas exploration blocks to energy firms in 2023 — welcome news for European governments looking to cut their energy dependence on Russia but grim news for the climate.

Russia looks north

Then there’s Russia — the country that more than any other has tied its economic future to the Arctic.

Already, about 20 percent of Russia’s GDP and 22 percent of its exports are generated in the Arctic region — mostly oil, gas and mining. Putin has come around in recent years to the seriousness of climate change — a problem he once dismissively joked would allow Russians to spend less money on fur coats — but he clearly sees melting sea ice as an opportunity.

In 2009, two German ships became the first commercial vessels to navigate the Northeast Passage from Europe to Asia via the Russian Arctic — a route that was once impassable but is now ice-free for much of the summer. In recent years, Putin has put forward ambitious plans for the Northern Sea Route, as the Russian portion of the passage is known, calling in 2018 for traffic along the route to reach 150 million tons of cargo by 2030. As of 2020, the figure stood at just 1.3 million.

The Northern Sea Route is also a key component of Russia’s Vostok Oil Project — a large-scale initiative to develop several new oil fields in the northern Ural region and export the oil via a new seaport on the Taymyr Peninsula in Russia’s far north. Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin predicted the project would create 100,000 new jobs and lead to a 2 percent spike in Russia’s GDP. That sounded awfully optimistic even before the war in Ukraine led European countries — the intended customers for the project — to cut their reliance on Russian hydrocarbons.

The Russian government now hopes to reorient its exports toward customers in Asia, who are still buying Russian oil at steep discounts. But it’s not clear when, if ever, this route will be economically viable.

“Putin had very ambitious goals for monetizing the North Sea route, but those have fallen off, and I don’t see that happening any time soon,” said Goodman, now a global fellow at the Wilson Center’s Polar Institute.

For now, plans to make the Northern Sea Route a major shipping lane are years away. But Russia still has immense reserves of Arctic oil and customers to buy it — via pipeline, train or other means. The country’s fate is too bound to the energy riches underneath its Arctic territory to abandon them.

A new Arctic discovery

Even if concerns about climate change and the plummeting price of renewable energy lead some countries to leave their Arctic oil and gas in the ground, that doesn’t mean governments will lose interest in the region’s economic potential.

Last month, Sweden announced the discovery of “significant deposits” of rare earth elements — required for the production of many electronics as well as electric vehicles and wind turbines — in its far north. Norway has also found substantial deposits of these metals on its Arctic seabed. The discoveries have provoked enormous excitement in Europe, which currently imports 90 percent of its rare earth metals from China.

But Arctic residents like the Sámi — the Indigenous people of Northern Scandinavia — say mining is already disrupting their region’s environment and their way of life.

These metals may be vital for a world trying to wean itself off fossil fuels, but that doesn’t mean the Arctic will be left pristine in the “green transition.” Goodman told Grid that while the actual process of mining these resources “won’t happen overnight,” it’s clear that “this is the future of valuable commodities, and the future is just about here.”

China has also sought to establish itself as a scientific leader in the region, with research stations spread throughout the Arctic from Norway’s Svalbard to Iceland, and many joint research projects to study the sea ice and other climatic conditions.

But Odgaard and Sacks said there is basis for concern that China’s scientific research stations may be doing more than studying the ice. China’s limited Arctic footprint is “actually enough that they can use it for surveillance, intelligence and reconnaissance,” Odgaard said. For now, though, China has neither the appetite nor capacity for a significant military presence in the Arctic, she added.

Thanks to Lillian Barkley for copy editing this article.